I recently took part in a symposium on the condition of democracy in America. Panelists were asked what advice they would give the American people to improve the political culture in this country. I suggested a conscious effort to assume the sincerity and good intentions of people we fundamentally disagree with. I said this would be good for us as individuals; it's always beneficial to question our own infallibility. And it would be good for the country, as it would make necessary compromises easier.

The audience as a group seemed to think this a reasonable idea. At least they didn't boo. But after the session a member of the audience came up and said she just couldn't do it. Her neighbor, she said, was a white nationalist. Try as she might, she couldn't get past that. Nor did she think she should. He was wrong, and any compromise with him would lead the country further down the bad path it was on.

I would have liked to discuss the issue with her further, but the next session was about to begin. In other comments I had said that the last six or eight years had been gratifying for people who like to treat politics as a morality play. Each side has given the other reason to think good rests entirely with their side and evil with the other. Donald Trump daily made Democrats think that whatever their own faults, these were so much less than his that they had a monopoly on justice and decency. Republicans reciprocated, painting the Democrats with the brush of wokeism and socialism, so that whatever the excesses of Trump, he was the bulwark of the country against the terminal decline the Dems would bring on.

In our brief conversation, the woman who approached me said she didn't treat politics as a morality play. But she insisted that morals should play a role in public life. And the idea of compromising with the bad man who was her neighbor was more than she could accept.

I would have asked her what made her think he was a bad man. What did she mean by white nationalist? Did he parade in a Ku Klux Klan outfit? Did he say that immigrants were ruining the country? Did he praise the Supreme Court's decision to outlaw affirmative action? The problem with labels is that they mask differences that might be important. In politics, they tend to impute the worst tendencies of extremists to people who actually hold milder views.

Even assuming that this fellow held the worst of the views associated with the term white nationalism, I would have pointed out that he gets to vote. Perhaps she could find no common ground with him on issues touching race, but there are other matters in the public arena that have to be dealt with. Maybe they both had elderly parents who suffered from dementia, and they could agree that more money should be spent on research in that area. Maybe they both were fed up with the traffic in the greater District of Columbia area, where the symposium was held, and thought something should be done to address that.

Since our conversation, I've wondered if I was asking too much. Can people really set aside their moral beliefs to find common ground with those they disagree with? This woman placed moral principle ahead of political progress. She simply didn't want to have anything to do with her neighbor. Maybe that's an appropriate ordering of priorities. Politics isn't everything. Self-respect counts too.

But if everyone, or most people, took that view, our democracy might be doomed. I have no way of knowing for sure, yet I suspect this woman wasn't happy with the overturning of Roe v. Wade. But for people who believe that a fetus is an unborn child, every abortion is a murder, and decent people should do their best to stop murders from happening. Indeed, on principle, the next step after the decision in Dobbs should be a campaign to pass a federal law against abortion.

The problem, of course, is that most people in the country don't want such a law. They have their own principles. And this is where the moralistic approach to politics breaks down.

We've traveled this road before. By the 1850s, American abolitionists were so convinced of the evil of slavery that they were willing to countenance almost any act in opposition to it. And they were opposed to almost any compromise with those who disagreed. The Compromise of 1850 provoked outrage in the North by its insistence that northern authorities assist in the return of fugitive slaves, as Article IV of the Constitution requires. Northern abolitionists tried to block the enforcement of the law; some advocated secession from the Union lest they be tainted by this unholy compromise with the devil.

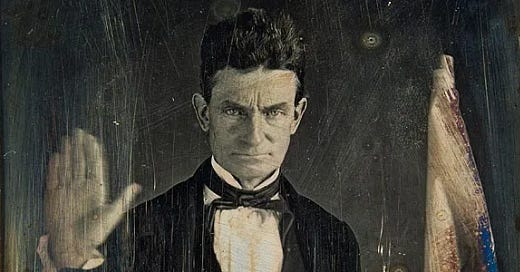

After the Kansas-Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise’s ban on slavery in most of the trans-Mississippi West, abolitionist John Brown led a small band of militants who slaughtered pro-slavery settlers in Kansas Territory. Abolitionists applauded Brown's murderous action on the argument that violence against slavery’s supporters was justified by the violence that had been inflicted on slaves for centuries. New England abolitionists channeled money to Brown to support further violence against slavery and slave holders.

Moderate anti-slavery men like Abraham Lincoln agreed with Brown that slavery was wrong. But they decried his violence as wrong in itself and counterproductive besides, for causing the slave states to dig in their heels deeper than ever.

The result was the Civil War. It ended slavery, at great cost, and confirmed in much of the North the canonization of Brown, who was seen as John the Baptist to Lincoln’s Jesus Christ.

The moralization of politics today has yet to produce a John Brown. And we are, I hope, a long way from another civil war. Yet the self-righteous tone on both sides of our political divide bodes ill for the future. At best, it condemns us to continued gridlock. At worst, it will drive some people to violence they consider principled and necessary, and cause other people to applaud the violence.

If you find yourself humming “John Brown’s Body," stop and ask yourself if you really think that's an appropriate anthem for America now.

Another thought-provoking post, Bill. It reminds me of this comment you made on a previous post, "Moralism in politics":

"Militants have often been the ones to topple the old regime, but they have rarely been good at building a replacement. The Sons of Liberty helped start the Revolutionary War, but Washington and Franklin had to fight and end it, and they and others had to write the Constitution to get the successor government on a solid footing. Brown prompted slaveholders to challenge the Union militarily, but Lincoln was the one who ended slavery. Malcolm X energized black protest in the 1960s, but Martin Luther King did more to end segregation. The militants often get better historical treatment, being more dramatic and sure of themselves, but the pragmatists are the ones who actually move history forward in a way that lasts."

https://open.substack.com/pub/hwbrands/p/moralism-in-politics?r=kgnhx&utm_campaign=comment-list-share-cta&utm_medium=web&comments=true&commentId=3057279

By the way your book The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln, and the Struggle for American Freedom was excellent!