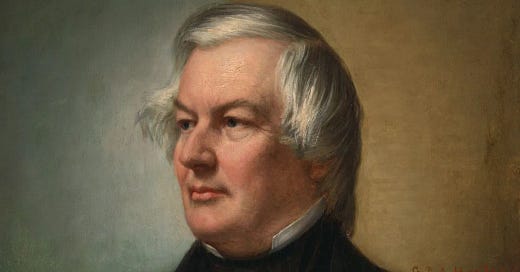

Millard Fillmore was the second vice president to become president upon the death of his predecessor, and the first to be taken by surprise by the event. William Henry Harrison had been sick for a month before he died in 1841 and made John Tyler president. Zachary Taylor, by contrast, fell suddenly ill in 1850 and died within days, making Fillmore president.

The timing could hardly have been worse. Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky had proposed a multipart legislative package designed to admit California to the Union as a free state without alienating the slave South. The principal sweetener for the South was a toughened fugitive slave law, drafted to defeat growing efforts by northern abolitionists to facilitate the escape of slaves from bondage.

Clay's package had something for everyone to dislike, and during the early summer of 1850 the dislikes appeared to outnumber the likes and doom the grand compromise. Clay himself almost lost hope. He stepped aside to let others take charge of the bill.

Quickest to the front was Stephen Douglas of Illinois. Douglas was a Democrat and aspired to the presidency. He observed that Clay's compromise was creating a rift in the Whig party of Clay and Fillmore which might be widened into an avenue to the White House. Douglas dismantled Clay's package and arranged for separate votes on the individual parts. At a time when no single majority was available for the package as a whole, different majorities were cobbled together for the separate parts, which became law one by one.

All that was left was for Fillmore to accept or sign the several measures. Taylor, a Virginian, hadn’t committed himself on the compromise by the time of his death, but he was thought to sympathize with the South. New Yorker Fillmore was believed to lack such sympathy. By no means were all northerners abolitionists or even ardently opposed to slavery, but nearly all resented what they took as the arrogance of southern slaveholders.

As a pro forma gesture, the cabinet secretaries Fillmore inherited from Taylor submitted letters of resignation. To their chagrin Fillmore accepted them. He remembered how holdovers from Harrison's administration had subverted Tyler’s presidency, and he sought to preempt such attack.

As secretary of state he appointed Daniel Webster of Massachusetts. Webster was the last man standing of the great Senate triumvirate of himself, Clay and John Calhoun. But Webster had made himself odious in Massachusetts, the hotbed of abolitionism, by voting in favor of the Fugitive Slave Act, on grounds that its rejection would doom the Union. Webster realized he wouldn't be reelected to the Senate. The state department seemed a refuge.

From Fillmore's perspective, Webster provided political cover. Critics of the fugitive law vented their outrage on Webster, causing Fillmore's acceptance to go comparatively unnoticed.

The two men congratulated themselves on the Compromise of 1850, as the several measures collectively were called. At times during the Senate debate — the first part of which Fillmore had presided over in his vice-presidential capacity as president of the Senate — angry southerners had seemed on the verge of stalking out of Congress and leading their states out of the Union. The compromise averted this and bought time for a larger reconciliation.

The reconciliation didn’t come. Radical elements in both North and South brooded on the parts of the compromise they didn't like and became more intransigent. A decade after the compromise, the election of Abraham Lincoln triggered secession, which precipitated the Civil War.

Fillmore's effort on behalf of the Union won him no thanks. The Whigs refused him their 1852 nomination, which wasn't worth much anyway, as the sectional dispute cleaved the party on its way to dissolution. Historians subsequently gave Fillmore no better than the back of their hands.

But in fact he did about as well as anyone could have in his situation. He had no mandate from voters and faced stiff opposition in his party. The prudent and ethical course was to do what he did: follow the lead of Congress, as the framers of the Constitution intended presidents generally to do.

Leaders inevitably encounter moments when none of their options are good. The best course is to choose the least bad. This won’t make you a hero. Don’t worry. Heroism is overrated.

Thank you for sharing this history Dr. Brands. This and similar posts of yours help bring important history to life, and in fact greatly comfort me as our own period of history unfolds.

Zachary Taylor apparently considered his home state to be Louisiana, not Virginia, as he invested in Louisiana real estate and was stationed in Baton Rouge for a time. He is buried in Louisville, KY as that was where he was raised and lived as a young man. He could also call Mississippi home as he had plantations there too. A very antebellum South All-American man.