Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.

So wrote Karl Marx in 1852 in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Marx was recounting the French revolution of 1848 and its aftermath, culminating in the 1851 coup by which Louis Napoleon, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, made himself emperor. Marx’s point was that Napoleon III was no Napoleon I. In this same work, he said that history repeats itself: “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”

Marx got a lot wrong in his long career of writing and agitating. Communism never overthrew world capitalism. At least it hasn’t yet. But his observation about the limits of humans’ ability to make history has broad application. And it ought to be considered by those inclined to impute folly or venality to the actions of their forebears.

Lead pipes were common in plumbing in the United States and other countries a hundred years ago. In the 1980s Congress prohibited their use in new construction, following research showing that lead contributes to learning disabilities and behavioral problems in children. But lead pipes continue to deliver water to millions of households across America today.

It’s not as though the toxicity of lead was news. The Romans realized it could cause trouble, even as they pioneered its use in plumbing (from the Latin plumbum, for lead) and in pigments for paint and pottery glazes. But lead was simply too cheap, convenient and useful to forgo. It is easily found, smelted and worked.

And—here’s the essential point—it was better than the alternatives. The Romans realized they would die sooner from water-borne diseases without their lead pipes than from the constipation and trembling sometimes produced by chronic exposure to low levels of lead. Today lead pipes can be replaced by copper, galvanized steel or PVC. These weren’t available at scale or at all then; the alternative to the use of lead pipes was polluted water delivered by leaky wooden pipes.

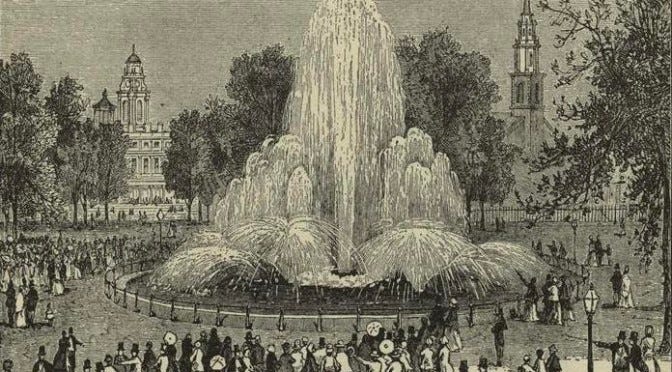

That calculation continued to hold true for two millennia. When (lead)-piped water replaced backyard wells in the cities of America in the nineteenth century, residents reveled in their liberation from cholera and its kindred scourges. A New York bard penned an ode to clean water when the Croton reservoir opened in the 1840s.

Gushing from this living fountain,

Music pours a falling strain,

As the goddess of the mountain

Comes with all her sparkling train.

From her grotto-springs advancing,

Glittering in her feathery spray,

Woodland fays beside her dancing,

She pursues her winding way.

Asbestos has a similar story. The ancient Egyptians knew about this miracle substance: cheap, easily fashioned and impervious to heat. Well into the second half of the twentieth century it was a mainstay of builders and even do-it-yourselfers. In 1976 I wanted to install a wood stove in my house, but the living room wasn’t large. So I went to the local building supply store and bought a sheet of asbestos board. With a handsaw that created clouds of asbestos dust, I cut the board to make a heat shield I fastened to the plaster walls. The system worked perfectly; the house was toasty all winter.

And it didn’t burn down. Here again the issue was comparative risk. The asbestos industry in all its phases has produced many thousands of deaths from asbestosis and lung cancer. But the use of asbestos saved many millions of lives that would have been lost to fire. These days we don’t use it; we’ve devised replacements. Our grandparents didn’t have that luxury.

Climate warriors today encounter the frustrations of Marx’s dictum. Many wish to get people out of their cars and onto mass transit. More than a few of those people themselves would like nothing better. But the current generation in America has inherited cities and suburbs built in the golden age of the automobile, when inexpensive land and plentiful gasoline made spreading outward irresistible. Few American cities have the density required for mass transit to be an attractive alternative to cars. Cityscapes change, but slowly. The tradition of dead planners weighs upon the living, if not like a nightmare on the brain then like a pain in the neck.

What’s the answer?

Something Marx found hard to summon, even though his historical writings pointed in its direction. His polemics preached revolution, but his analysis taught evolution. Change is possible, but it comes slowly. It requires patience and persistent effort. We can make history, but not as quickly we please.

If I may introduce a bit of humor into a serious discussion:

Drink is the curse of the working class. (Karl Marx)

He had it wrong: Work is the curse of the drinking class. (Groucho Marx)

Another excellent essay! The main criticism I've heard of Marx is that he failed to see the rise of the middle class. In other ways, however, most countries have adopted Marx's social message. I remember when the Wall fell in 1989, the Nation had an excellent article titled "Borderline Marxists." The point of the article was that West Germany had put into practice much of Marx's social message (minimum wage, free medical care, etc.). So, it wasn't a simple case of the Wall's coming down proving that Adam Smith was right and Karl Marx was wrong.