Liberalism and its discontents

A paradox of progress

Once is a curiosity, twice a coincidence, three times a trend.

After their recent defeat at the polls, American Democrats are understandably asking themselves what they should have done differently. Dump Biden sooner? Make Kamala Harris earn her nomination? Lay off identity politics? Double down on identity politics?

These can be useful questions. But they might not get to the heart of the matter. They assume that what happened in America is explainable by events in America. What if the explanation is bigger than that?

The rise of Donald Trump has been likened to the rise of Andrew Jackson. In each case voters registered a decisive distaste for a status quo they saw as arrogantly out of touch with issues important to the daily lives of ordinary people.

As always, broad-brush explanations like this ignore important elements of the story. Jackson’s thundering against the national bank, for instance, resounded not simply with common folks but with the local elites who owned state banks. In neither of Trump’s two victories did he receive a majority of the popular vote. One has to be careful not to explain too much.

Yet something important happened. And not in America alone. Populist movements have shaken the status quo in numerous countries during the past decade. From Brexit to the recent collapse of governments in France and Germany, with stops in Poland, Hungary, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands, a rejectionist wave has swept across Europe. An Americas version of the same phenomenon installed a government in Argentina and threatens to do so in Canada, besides electing Trump for the second time.

What’s going on? And why in so many places?

A first thing to note is that these are mostly countries with traditions of liberal—in the sense of free and competitive—politics. Poland and Hungary are exceptions, having been under the Soviet thumb during the Cold War. A second is that their economies were doing reasonably well, by historical standards. Argentina is the outlier here, having suffered debilitating inflation for years. In other words, the status quo wasn’t intolerable, even if majorities of voters eventually didn’t tolerate it.

This is a key point. Open political systems are prone to populism precisely because they are open. Daily life is objectively harder in China, Russia and Iran than in Britain and Belgium, but the authoritarian regimes in those countries brook no dissent. In other words, the countries where popular dissatisfaction is most evident are countries where it is comparatively mild.

There is an important historical experience common to the countries manifesting populism today (again excepting—partially—the former communist countries). Their political and economic systems grew out of the enormous turbulence of the first half of the twentieth century, in particular the two world wars and the great depression between. The people who experienced these calamities knew how bad things can get, and they never forgot. They judged the circumstances of the post-1945 era to be a distinct improvement over what they had been through.

But they died, and their children and grandchildren grew up with a different baseline against which life was measured. One of the surprising things about the current wave of populism is that it is occurring amid relatively benign economic conditions. Fascism—the dominant populist mode of the twentieth century—flourished in the depression of the interwar years. Our economic situation is nothing like that. Even the inflation that has so bothered Americans of late is modest compared with the inflation of the 1970s.

In certain respects, the countries where populism is most evident today are victims of their own success. Excessive immigration is a common complaint in several of these countries, where locals feel they are overwhelmed by foreigners. Perhaps needless to say, immigrants are drawn to countries that are successful, not those that are failing. North Korea has no immigrant problem, nor does Russia. China’s immigrant worries focus on North Korea, where life is even harder.

Dissatisfaction with elites is real. But this falls into the category, characteristic of open politics, of what have you done for me lately? The elites brought eighty years of peace and prosperity. To be sure, the elites succeeded better than many ordinary people. Yet the average standard of living in America and most of the other countries is far above what it was in 1945.

Again, this means little to people born decades later. They know what they know, not what their grandparents knew.

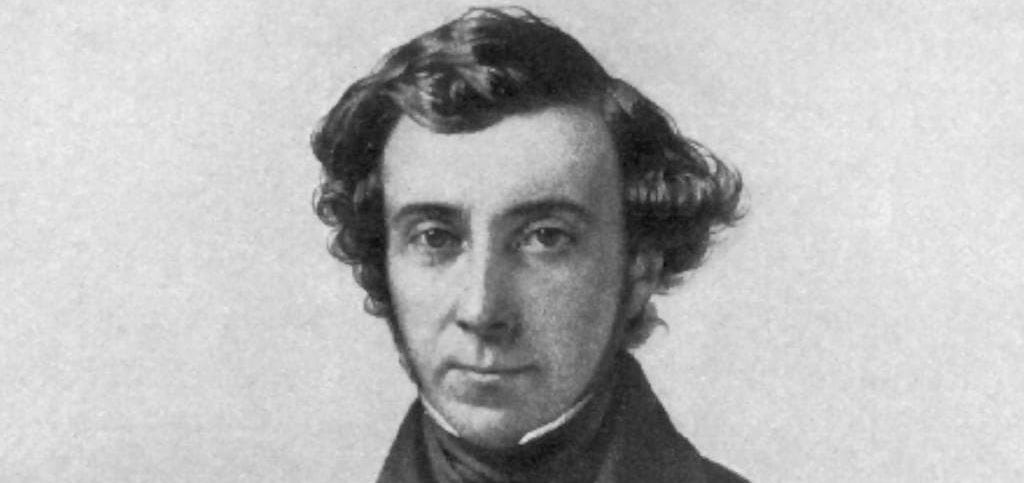

And it raises a basic question about liberal societies. Are they forever doomed by their own progress? Alexis de Tocqueville observed a paradox of revolution: “It is not always by going from bad to worse that a society falls into a revolution. It happens most often that a people which has supported without complaint, as if they were not felt, the most oppressive laws violently throws them off as soon as their weight is lightened.” After World War II a school of political and sociological thought stressed the “revolution of rising expectations” that was sweeping across colonized Africa and Asia. A homespun version remarks that appetites grow with the eating. The better the lives of people get, the more they demand that they get still better.

If this were merely a matter of perception, it would be cause for concern but not alarm. But in fact there’s a greater risk. The populists aren’t likely to make things better, given that things are pretty good to begin with. In their insistence on change, the populists are likely to make things worse.

Maybe much worse. Let’s think: what could have been worse than World War I and the great depression? How about World War II, which is what the populist-fascists wrought? America started down this road under Trump with his trade war against China. The trade war escalated under Biden, and is likely to escalate further under Trump again. A regular war against China is hardly out of the question, and is being made more likely by the belligerently nationalist talk in both parties.

Leninists used to say that things had to get worse before they got better. For the populists, things apparently have to get better before they get worse. Neither is much of a formula for human happiness.

Nice read as always Dr. Brands.

I have to wonder if one factor of difference between the people today and those in the past is also how we consume information.

People of the past had limits on what information they could get and they certainly didn't have information that was catered to them alogrithmically to reinforce their own beliefs that things are worse than they really are.

There are plenty of people I know and respect who truly believed that America was on the brink of collapse due to the information they consumed.

Do you think the current populist wave is not just due to progress but also the proliferation of information to convince normal people that things really are dire?

Dr. Brands, I really enjoyed your article "Liberalism and Its Discontents." I think you make some very valid points about the causes of mass movements and the role of political polarization in those movements.

I also noticed that Eric Hoffer points out something similar in his book "The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements." In that book, he argues that poor people are not usually the ones who join revolutions. Instead, he says that people who have seen a sharp drop in their standard of living are much more likely to get caught up in a cause like this because they can still remember how good they used to have it, and thus are more prone to feel that their circumstance was a product of corruption or treachery.