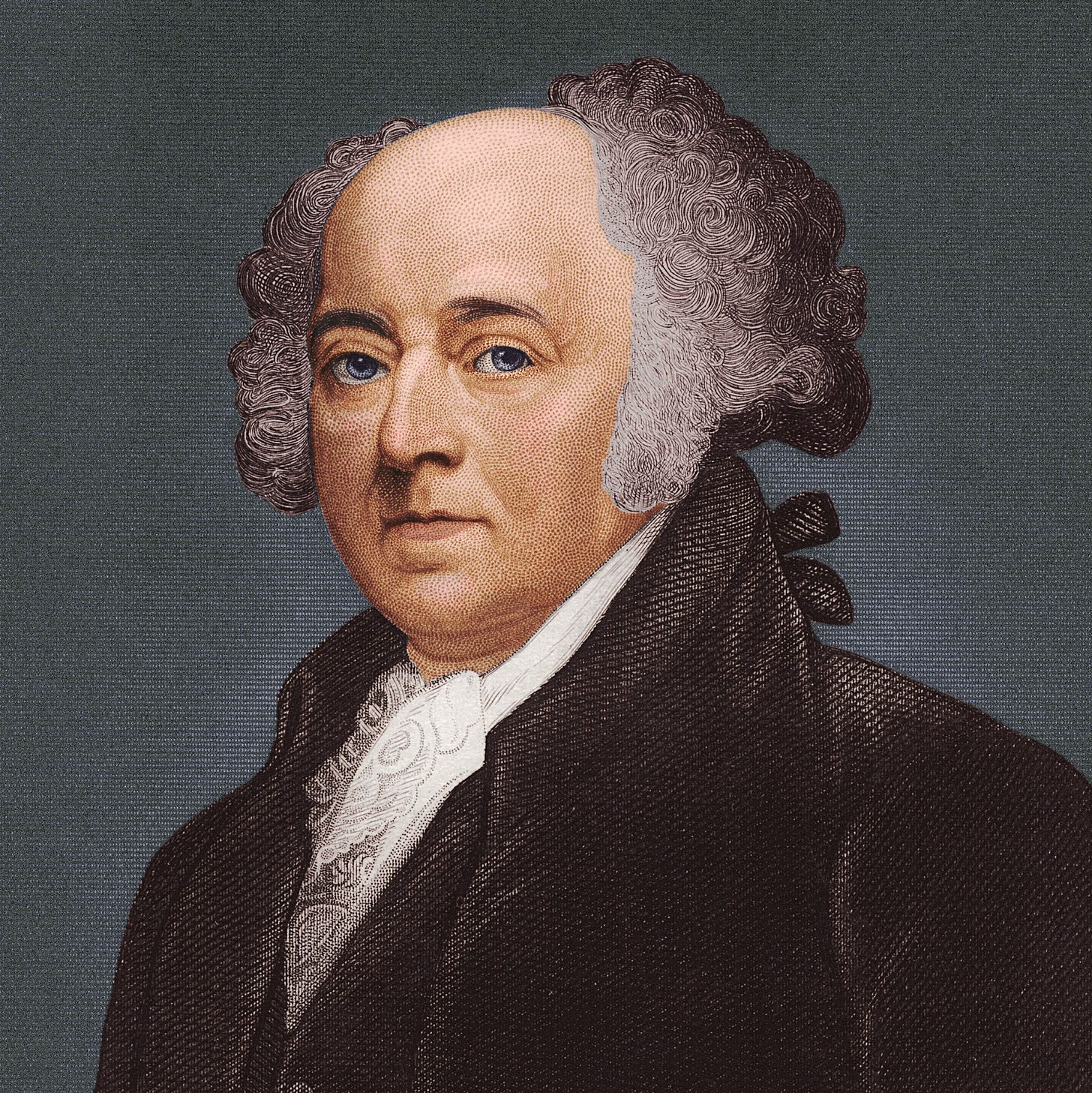

John Adams was the most democratic of the major founding fathers. To some degree this reflected his comparatively humble roots, measured against such Virginia grandees as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Adams received a good education, at Harvard College, but the rest of his success owed to his ambition and hard work.

Yet Adams was unable to embrace a fundamental principle of democracy, namely that everyone is entitled to an opinion and to the right to express it. Dictate opinions or penalize expression of them and democracy quickly dies.

Adams pleaded danger to the nation. Opinion suppressors always do. The second president shared the suspicions of France held by most members of his Federalist party. Provocations by France, principally seizures of American merchant ships on the high seas, prompted Adams to request appropriations from Congress to prepare an army for war against France. At the same time he launched an undeclared naval war against French ships.

To secure the home front, Adams and Federalists in Congress collaborated to produce the Alien and Sedition Acts, a four-part package designed to diminish the alleged influence of foreigners in American politics and to silence the opposition Republican party. Three parts of the package dealt with aliens, making it more difficult for them to become citizens and easier for the government to deport them in the event of war or national emergency.

The fourth part, the Sedition Act, declared that “if any person shall write, print, utter or publish . . . any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or either house of the said Congress, or the said President, or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute,” such persons would be guilty of sedition and subject to fine and imprisonment.

The Alien Acts were understood to be targeted against the Republicans, who were thought by the Federalists to benefit from the votes and support of immigrants. The Sedition Act was clearly aimed at critics of the Federalist president and Congress. Its aim was underscored by the final provision of the act, which called for its expiration at the end of the current presidential term. In other words, if the Federalists should lose control of the presidency, they wanted to be able to criticize a Republican successor to Adams.

The Alien and Sedition Acts turned out to be the greatest blunder of Adams's presidency. They didn't accomplish what he hoped for them and they produced a backlash he hadn't anticipated. No one was deported under the Alien Acts, and relatively few editors were arrested under the Sedition Act. Yet the arrestees included Benjamin Bache, a firebrand who died of yellow fever while awaiting trial, and thus became a martyr to free speech. Moreover, the measures proved unnecessary when the war against France never escalated beyond occasional actions at sea.

The Alien and Sedition Acts unified energized the Republican opposition. Its leader was Thomas Jefferson, who was vice president by virtue of being runner-up to Adams in the electoral voting for president in 1796, under the original scheme for choosing vice presidents. Jefferson and fellow Republican James Madison covertly coached the legislatures of Kentucky and Virginia to pass resolutions condemning the Alien and Sedition Acts and pioneering the doctrine of nullification, which proclaimed a right of states to resist enforcement of federal laws they considered unconstitutional. The corollary to nullification was secession, which eventually broke the Union in the 1860s.

More immediately, popular outrage at Adams and the Federalists led to their overthrow in the 1800 elections. Jefferson soundly defeated Adams in a rematch of their previous contest.

The rules of American democracy were still taking shape. Americans hadn't agreed on the principle of judicial review, by which the Supreme Court could declare laws unconstitutional. Yet Americans broadly believed that Adams and the Federalists had gone too far in trying to suppress the opposition, and they practiced the principle of political review by rejecting the Federalists at the ballot box.

Things didn't have to happen this way. If Adams had been willing to accept the idea that criticism comes with the territory of democratic politics, he wouldn't have committed the action that prompted the reaction that drove him from office and, as it turned out, consigned his party to oblivion. Adams was the first Federalist president and the last.

All for naught. The Quasi-War, as the desultory conflict with France was called, came nowhere near threatening American security and ended with a shrug eighteen months after it started.

The lesson for other leaders is to worry less than Adams did about criticism. Mind your job and let the critics rail. If you react, you'll probably overreact. You might not lose your job, as Adams did, but you won't do yourself any good.

I really like the line at the end of the piece: “Mind your job and let the critics rail. If you react, you'll probably overreact.” It reminds me of what Ian mackaye of the band Fugazi once said, “other people say who you are and if you try to sway it it becomes an issue of propaganda. You are creating a false medium.”

Ive always been curious about this in your work and other historians: what do you mean when you use the term “democratic” or “democracy” ? Is it different than the classical greek conception of unlimited majority rule? Do you mean universal suffrage? I find it very confusing.

This quote from Adams seems to suggests that he conceived of democracy in the classical unlimited majority rule and therefore see’s the American republic as a system limited , i assume by natural rights of individuals inalienable by any majority:

“I do not say that democracy has been more pernicious on the whole, and in the long run, than monarchy or aristocracy. Democracy has never been and never can be so durable as aristocracy or monarchy; but while it lasts, it is more bloody than either. … Remember, democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide. It is in vain to say that democracy is less vain, less proud, less selfish, less ambitious, or less avaricious than aristocracy or monarchy. It is not true, in fact, and nowhere appears in history. Those passions are the same in all men, under all forms of simple government, and when unchecked, produce the same effects of fraud, violence, and cruelty. When clear prospects are opened before vanity, pride, avarice, or ambition, for their easy gratification, it is hard for the most considerate philosophers and the most conscientious moralists to resist the temptation. Individuals have conquered themselves. Nations and large bodies of men, never.”