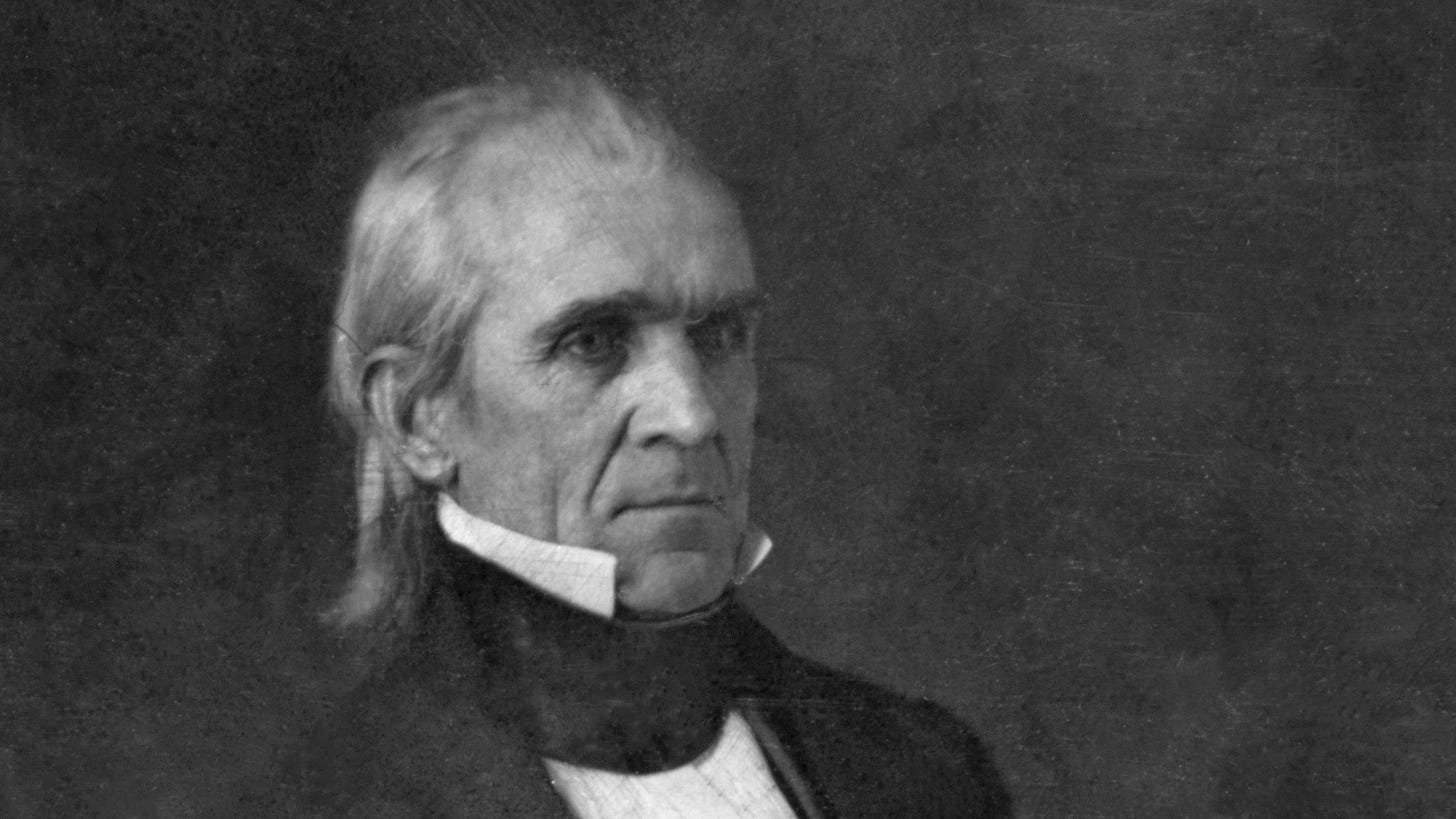

George Washington is applauded for having established the principle that no president should serve more than two terms. James Polk admired Washington but thought he could do him one better — one term better, to be precise.

“I deem the present to be a proper occasion to declare that if the nomination made by the convention shall be confirmed by the people and result in my election, I shall enter upon the discharge of the high and solemn duties of the office with the settled purpose of not being a candidate for re-election,” Polk declared upon receiving the Democratic nomination in 1844. "In the event of my election, it shall be my constant aim, by a strict adherence to the old republican land marks, to maintain and preserve the public prosperity, and at the end of four years I am resolved to retire to private life."

It was a fence-mending gesture. The contest for the Democratic nomination that year had been bruising. Polk was the compromise choice when none of the leading candidates succeeded in gaining the two-thirds majority of convention delegates Democratic rules required. By limiting himself to four years, Polk gave the losers hope they might still find their way to the White House.

Yet Polk realized that limiting himself to one term had advantages in its own right. Presidents and other office holders whose terms have a definite end-date are called lame ducks. The presidents in particular are lame because they strike no terror into their opponents, who are tempted to wait them out.

Polk had a different perspective. He judged that his one-term pledge would elevate him above politics. His actions would not be viewed through the lens of their effect on a reelection campaign. When he said he was working for the national interest, he would be taken more seriously than many presidents are.

Whatever the effect on voters of the one-term promise, Polk won the 1844 general election. He thereupon set himself to getting things done. His agenda was straightforward. "There are four great measures which are to be the measures of my administration," he said, according to the recollection of George Bancroft, the navy secretary. “One, a reduction of the tariff; another, the independent treasury; a third, the settlement of the Oregon boundary question; and lastly, the acquisition of California."

Polk's first two measures were accomplished by the standard methods of politics. His Democratic party had always disliked the high tariff favored by the Whigs, and the victory he and they won in 1844 allowed them to revise the tariff downward. The independent treasury combined the less controversial elements of the national bank dismantled by Andrew Jackson and the state banks whose unbridled lending had resulted in the financial panic of 1837. Again, this was a matter for legislation: the Independent Treasury Act of 1846.

The Oregon boundary was settled by negotiation with Britain. During his election campaign Polk had spoken belligerently. The rousing slogan was “54-40 or fight,” referring to the extreme northern border of the Oregon country, far above the 49th parallel, which farther east separated the United States from Canada. In office Polk settled for an 1846 treaty extending that parallel boundary to the Pacific.

Acquiring California from Mexico necessitated stronger measures. Polk tried to purchase California, but Mexico, having just lost Texas to the Americans, was in no mood to sell. Polk thereupon manufactured an incident on the border that allowed him to claim that American blood had been shed on American soil. Congress declared war, which didn't end until American troops occupied Mexico City and compelled the 1848 cession of California and New Mexico.

Like God after six days of creation, Polk after four years of the presidency surveyed his accomplishments and found them to be good. And in the fifth year he rested, which was to say he stuck with his promise to retire after one term.

His rest didn't last long. Three months after leaving office he contracted cholera and died.

This cast a pall over what might have been a worthy precedent. The example of a happily retired Polk would have encouraged successor presidents to emulate him and take the one-term pledge. America almost certainly would have been better off. Presidents’ second terms, from the 18th century until the 21st, have been mediocre at best and calamitous at worst. A first term president has energy and his pick of his party’s talent. By the second term the energy is gone and his team consists of second and third stringers. The important positive achievements from presidents’ second terms can be counted on one hand with fingers to spare.

The lesson applies to leaders generally. Front load your ambitions. Honeymoons don't last long. Take advantage of them. Like Polk, make a short list of what you want to do. Get it done and get out. You’ll be remembered for your accomplishment. If you don't get it done, get out anyway. Give someone else a turn. You’ll be remembered for your good sense and fair play.

Would that Biden had followed Polk's example.

Mexico said that a state of war existed if the US annexed Texas, which Mexico never acknowledged as independent. Polk tried to negotiate and Mexico would not even talk to his appointed representative. He didn't have to manufacture an incident. Mexican troops twice attacked US troops on land claimed by both countries. Mexico has traditionally been ruled by idiots, which is why Mexicans do so much better here than in their native country.

We started off with Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison and Monroe. They started off with the emperor Iturbide and Santa Anna. What could go wrong?