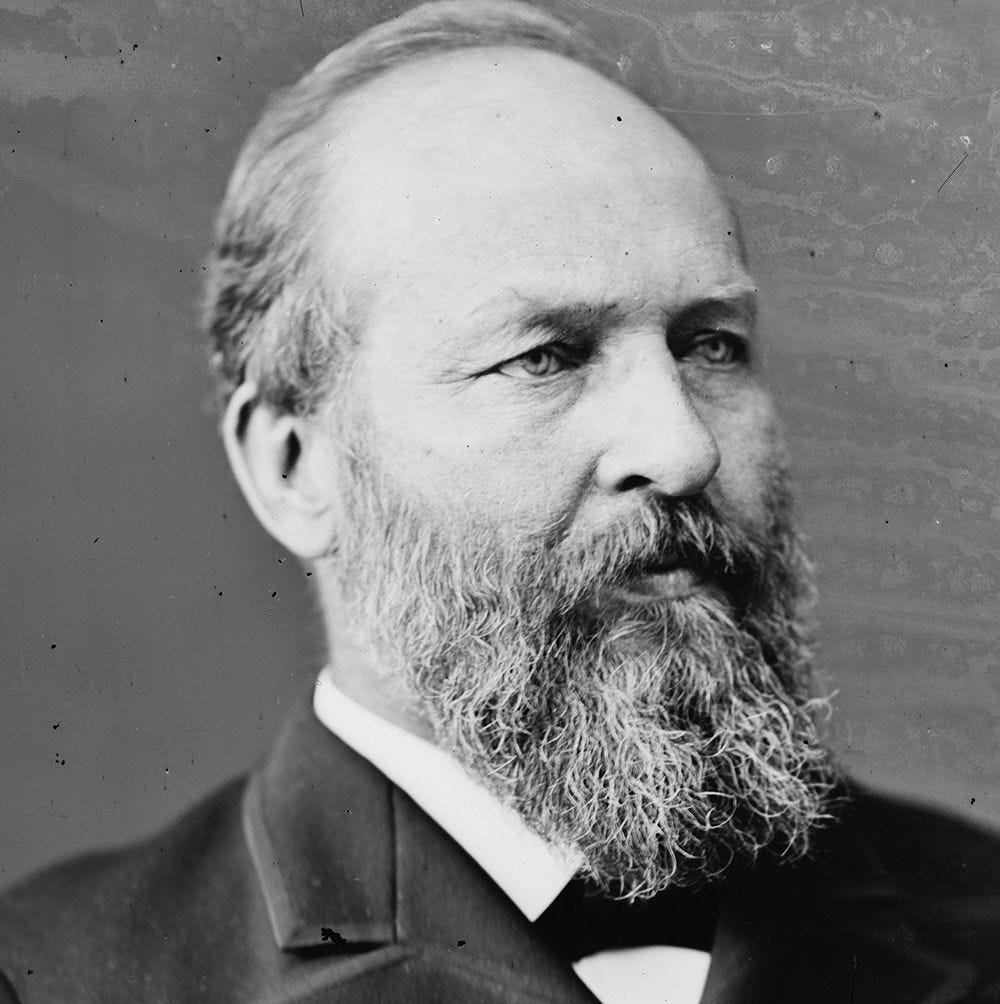

James Garfield: Pick your doctors carefully

Leadership lessons of the presidents

James Garfield might have made a good president. We'll never know, because he had bad doctors.

Garfield hadn't seemed destined for the presidency. He was a lawyer and preacher in Ohio before becoming a soldier in the Civil War, rising to the rank of major general in the Union army. During the war he was elected to Congress and he served in the House of Representatives until 1880, when a deadlocked Republican convention settled on him as a compromise between feuding factions in the party. The Republican hold on the electoral college persisted and Garfield was elected, narrowly.

In the first months after his inauguration, Garfield proposed legislation to reform the federal civil service. The patronage system, as the practice of using government jobs to reward political supporters was called, had become a headache for presidents and a target for reformers. New presidents were besieged by prospective office holders, who often had exaggerated ideas of their competence and what their efforts on behalf of the party entitled them to. A practice that once had made people happy evolved into one that left many people angry, as the applicants for positions far outnumbered the positions themselves.

One such angry office seeker was Charles Guiteau, who took out his anger on Garfield, shooting the president at a train station in Washington. Garfield's wound did not kill him at once, and as his condition stabilized the president and the public hoped for a full recovery.

But the wound festered and grew infected. Garfield's doctors had intended to leave the bullet in his body. This wasn't uncommon. Probing for slugs often introduced infection, while leaving them in place allowed them to become encysted and not particularly troublesome. A century later, when Ronald Reagan was wounded by a bullet from a would-be assassin, his surgeons almost left the bullet in his body because it was close to his heart and they feared trying to move it. Reagan's chief surgeon, however, decided to give removal one last try and retrieved the bullet safely.

Garfield's surgeons were thinking along similar lines, but their knowledge of infection and how to mitigate its risks was rudimentary. When Garfield didn't recover as quickly as they thought he should, they went in after the bullet. In doing so, they introduced new microbes that infected the wound and spread throughout his body.

He died two and a half months after the shooting.

He likely would have survived if his doctors had paid more attention to recent work by Joseph Lister demonstrating the importance of antisepsis in treating wounds. Or even if they had done nothing and left the bullet in place.

But their constant probing with dirty instruments fairly guaranteed Garfield's demise.

Yet in death Garfield accomplished an important part of his legislation program. Shamed by this tragic demonstration of the evils of the patronage system, Congress passed the Pendleton Act establishing the principle that federal employment should not be subject to the whims of politics.

Sadly, Garfield wasn't there to celebrate the victory. On the other hand, if he had been there, there might have been no victory.

Candace Millard wrote a really interesting book on Garfield's assassination called "Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President." I've had a few of my AP US History students read it for their winter book selection. They are always outraged at the doctors' incompetence and their belief that dirty medical instruments HELPED the healing process. And Guiteau? Well, he genuinely thought he'd get a federal job now that he had made Arthur President.......

and we now have a president intent on undoing the Pendleton Act and re-politicizing the civil service ala Jackson.