Is the world really smaller than it used to be?

When George Washington issued his farewell address in 1796 warning Americans against involvement in the affairs of Europe, that continent seemed far from American shores. A sailing vessel could require a month or two to traverse the Atlantic, and the return voyage was as long. A handful of back and forth messages might fill a year's time.

The Atlantic hadn't shrunk when James Monroe declared his eponymous doctrine in 1823. Monroe observed that the United States had not involved itself in the affairs of Europe, and he warned Europeans against involvement in the affairs of the Americas. This two-spheres approach characterized American foreign policy for a century, and it seemed to reflect obvious facts of geography.

But by the end of the 19th century it was being challenged. Part of the test was technological. Steam power made ocean travel more predictable if not always swifter. Unlike sailing vessels, however, steam ships required refueling, which made them dependent on coaling stations strategically located in waters the ships expected to ply. Theodore Roosevelt and other imperialists argued for acquisition of such stations in such distant locales like Asia. As part of the argument, they asserted that the world was getting smaller and the United States needed to protect itself by projecting power outward.

Woodrow Wilson didn’t agree with Theodore Roosevelt on much, but he did concur that events in places once considered far from American shores could have grave consequences for American life. Demolishing the conceptual wall the Monroe Doctrine had built between Europe and the Americas, Wilson took the United States to war in Europe on the reasoning that the world needed to be made "safe for democracy." If Germany triumphed in Europe, democracy in America would be imperiled.

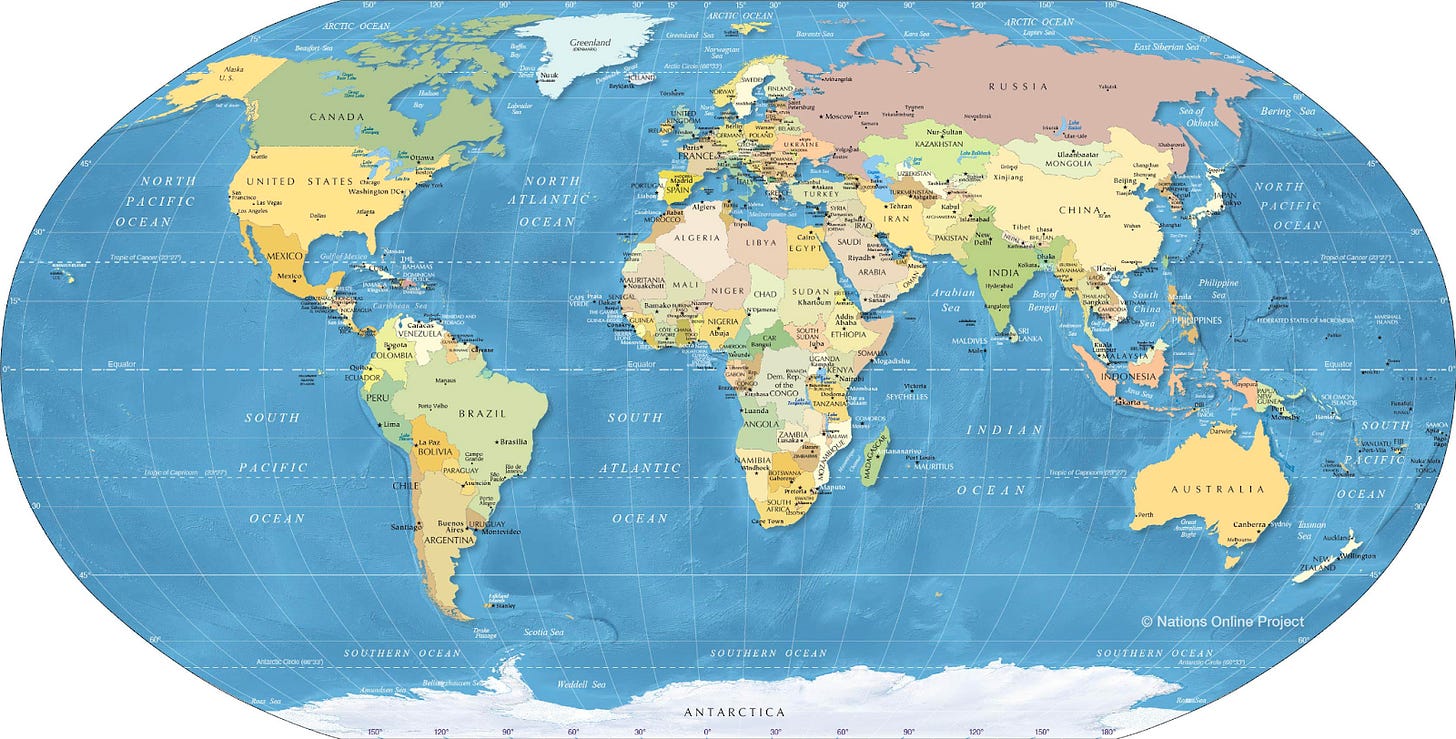

Franklin Roosevelt, a closeted Wilsonian during the 1930s, came out after Germany started another world war in 1939. Urging American aid for Britain, Roosevelt denounced the likes of Charles Lindbergh, who held that Britain’s problems were not America’s. “Some of us like to believe that even if Britain falls, we are still safe, because of the broad expanse of the Atlantic and of the Pacific,” the president said in a radio chat at the end of 1940. “But the width of those oceans is not what it was in the days of clipper ships. At one point between Africa and Brazil the distance is less from Washington that it is from Washington to Denver, Colorado—five hours for the latest type of bomber. And at the north end of the Pacific Ocean, America and Asia almost touch each other.”

Roosevelt was more explicit in private. Preparing his State of the Union address a few weeks later, he talked of securing freedom for people everywhere in the world. Adviser Harry Hopkins cautioned, “That covers an awful lot of territory, Mr. President. I don’t know how interested Americans are going to be in the people of Java.” Roosevelt replied, “I’m afraid they’ll have to be someday, Harry. The world is getting so small that even the people in Java are getting to be our neighbors.”

Nuclear weapons and missiles to carry them made the post-World War II planet seem smaller still. A missile launched from Russia could obliterate New York within half an hour. This perception underpinned the permanent readiness that characterized American military policy during the Cold War.

And yet in certain respects the world remains stubbornly large. To be sure, communication is more rapid than it was in the 18th century, although after the laying of transoceanic telegraph cables in the 19th century, people learned of events in distant zones almost in real time. The growth of international trade has made us business neighbors of people far away. And the weapons systems of the great powers can inflict swift damage across thousands of miles.

But the central question debated by Franklin Roosevelt and Charles Lindbergh was whether Germany posed a military threat to the American homeland. Lindbergh granted that German bombers might be able to stage demonstrative raids on American cities—much like the Doolittle raid on Tokyo after the United States entered the war against Japan. To invade the United States, however, Germany would have to transport troops across the Atlantic, much as the British had transported troops across the Atlantic during the Revolutionary War. In fact, the German transport would be more difficult, under the threat of American war planes. Nothing in the way World War II played out proved Lindbergh wrong.

Nor did subsequent wars much alter the reckoning. American troops were transported to Korea by ship and plane, and to Vietnam primarily by plane. But they still had to be transported. And they still fought for control of territory as soldiers had fought for territory for millennia. Indeed, the current war in Ukraine isn't very different from the Napoleonic wars in the recognition by both sides that control of territory will determine the war's outcome. A war over Taiwan might begin with attacks from a distance, but it won’t end in success for China until Chinese troops physically occupy the island. And, again because of advances in air power, transporting those troops across the Taiwan Strait will be more difficult than when Japanese troops seized Taiwan in the 1890s.

The rapid spread of covid made the world seem smaller than when influenza went pandemic in 1918, but the difficulties of containing it in nearly two hundred countries showed that our globe is still pretty big. Climate change underscores the confined nature of Spaceship Earth, but the inability of the passengers to agree on remedies reminds us that distance can be political and cultural as much as geographic.

Brands writes about travel in the "old days": "a sailing vessel could require a month or two to traverse the Atlantic, and the return voyage was as long." This was really borne home a year or so ago when I read McCullough's classic biography of John Adams. (David McCullough is my fave historian next to Brands.) Before he became president, Adams went to France on an important mission. Abigail Adams followed later. McCullough talks about the primitive conditions on her ship. Her maid had to hold up a curtain so she could dress unobserved by the crew. The voyage took over a month, with bad food, seasickness, poor sanitation, etc. It was a far cry from a diplomat's spouse today flying first-class and joining his/her spouse in seven-eight hours.