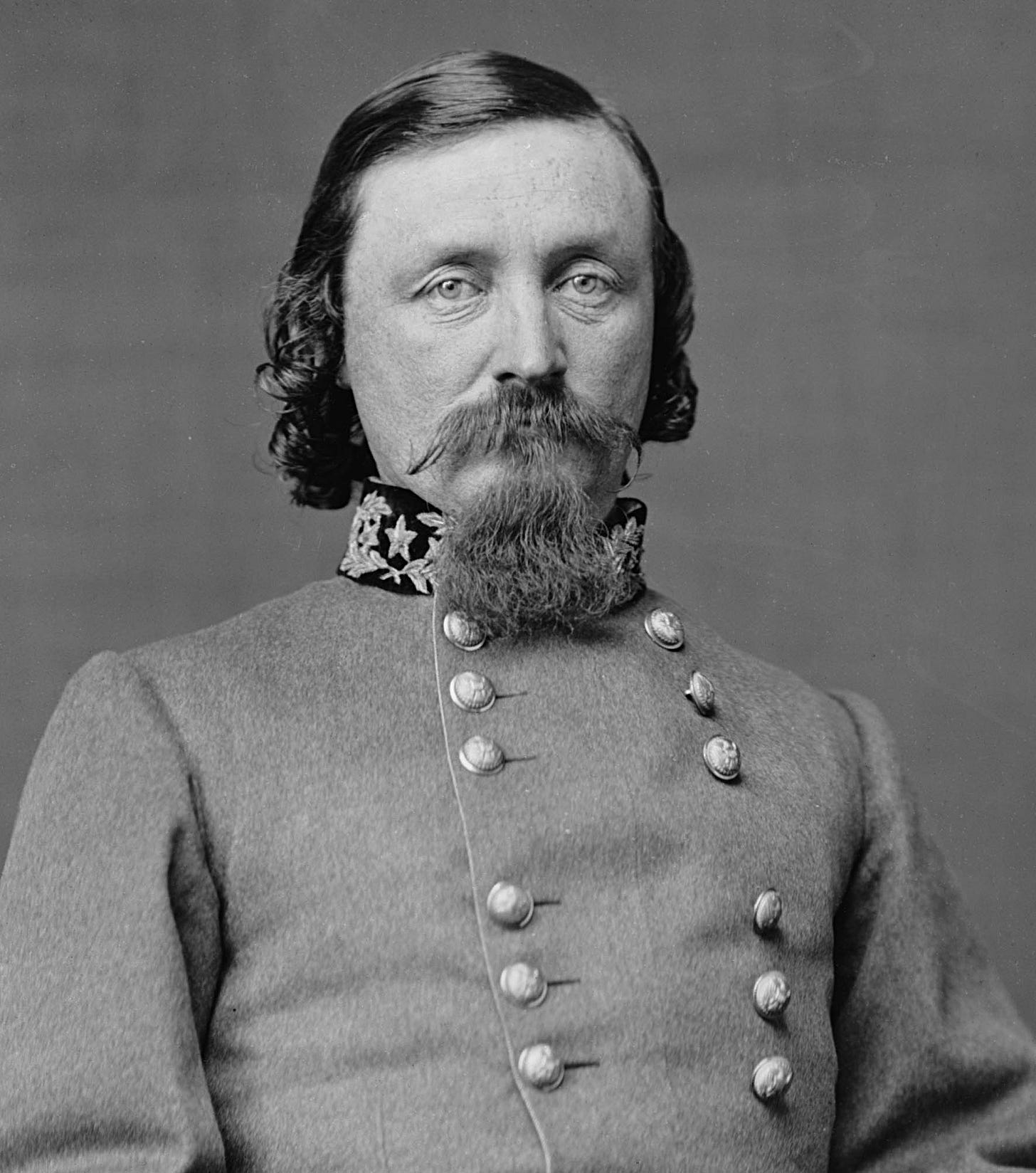

“For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it's still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out and Pickett himself with his long oiled ringlets and his hat in one hand probably and his sword in the other looking up the hill waiting for Longstreet to give the word and it's all in the balance, it hasn't happened yet, it hasn't even begun yet . . .”

So wrote William Faulkner in Intruder in the Dust, eight-five years after the battle of Gettysburg, which was decided by the failure of Pickett’s charge to dislodge the Union defenders of their central position on Cemetery Ridge. To Faulkner’s fourteen-year-olds, and to many other people, if Pickett’s charge had turned out differently, so might the Gettysburg campaign and the entire Civil War.

How would that have worked? What would it have meant?

Robert E. Lee had led his Army of Northern Virginia into Pennsylvania to pressure Washington from the rear. He didn’t expect to capture the Union capital, merely to show that the war Abraham Lincoln had insisted on waging wasn’t about to succeed. Lincoln would be up for reelection in little more than a year, and a discouraged Northern electorate might replace him with someone amenable to a negotiated peace, one that acknowledged Confederate independence.

This was the way the Revolutionary War had ended. The British defeat at Yorktown convinced the British government that a victory over the American secessionists would be too costly to be worth pursuing further. A Union defeat at Gettysburg might have a comparable effect on the Union government.

There was much to this argument. Even after the Union victory at Gettysburg, and the nearly simultaneous Union capture of Vicksburg, Northern spirits flagged in the summer of 1864 to the point where Lincoln anticipated losing his reelection bid. He wrote and sealed a memo outlining his response after his defeat. He never had to unseal the memo, because William Sherman’s capture of Atlanta and Phil Sheridan’s sweep through the Shenandoah Valley buoyed Union spirits sufficiently to carry Lincoln to reelection victory.

But suppose Lincoln had been defeated, and successor president George McClellan had negotiated a peace entailing Confederate independence. What then?

Two things at first: A second republic where only one had existed before, and the continuation of slavery. How long would these have lasted?

The answer is unknowable on both points. Regarding slavery, the likeliest answer is, Not long. Legal slavery had been nearly ubiquitous in the world in the eighteenth century; at the two-thirds mark of the nineteenth century it had almost disappeared. Changing attitudes accompanied changing modes of economic organization to doom the institution. Modernizing economies required flexible labor forces; employers had to be able to shed workers in response to downturns in demand. Labor forces under slavery were as inflexible as could be. If the Confederacy clung to slavery, it would consign itself to the backwaters of the world economy, besides making it a pariah in world opinion.

And if the Confederacy chose emancipation—rather than having emancipation forced upon it—the process might have gone better than the actual emancipation did. The Confederates would have had an incentive to make emancipation work, rather than the temptation to resist and sabotage it. In any case, in light of events of the next century, voluntary emancipation could hardly have gone worse—for the emancipated men and women, and for the South as a whole—than compulsory emancipation did.

Would the Confederate republic have lasted? Probably. Nations don’t lightly abandon independence, especially when hard-won. The Confederacy almost certainly would not have re-amalgamated with the Union.

Would it have broken into smaller pieces, as many critics of secession warned? Possibly, but probably not. A republic one-third the size of the United States in 1860 was plausible; much smaller than that and dis-economies of small scale began to set in.

Would subsequent wars between the United States and the Confederacy have occurred? This too was an argument raised by opponents of secession. Possibly, but probably not. Assuming an end of slavery, the major bone of contention between the two sections would have disappeared. Tariff policy, another divisive issue, would have been for each country to determine separately.

The most likely outcome would have been a gradual reknitting of the Union and Confederate economies, short of political reunion. This had happened between the United States and Britain after American independence. A commercial union was created in Europe after World War II, eventually giving rise to the European Union. A commercial union among the United States, Canada and Mexico was established in the 1990s.

In fact, something with characteristics of the EU and NAFTA would have been the most probable long-term result. Instead of three countries in NAFTA, there would be four. Or perhaps the three would be the United States, the Confederacy and Canada. And given their shared English language and heritage, the three countries might have extended their ties beyond the economic realm to mutual defense and some aspects of politics.

All this is speculation, of course. Which is just as well for Faulkner’s teen. He could dream, undisturbed by reality.

One problem that the Confederacy would have faced had all this happened is that it was a confederacy. That form of gov't had already demonstrated its weaknesses (i.e., the Articles of Confederation) and, I believe, even during the war Jefferson Davis had troubles convincing the states to act uniformly. I suspect that the Confederacy would have gradually crumbled with various southern states seceding from the secession and returning to the Union, leaving the diehards increasingly isolated.

Agreed with most thoughts on the South. Any reading of Oakes's scholarship shows the Stephens/Cruikshank of slavery forever had completely waned. I recommend Scorpion Sting for anyone who lives in this modern lens of Civil War scholarship that acted like slavery was not on its death throes is simply ignoring the vast majority of primary sources as well as all respectable historiography.

As I mentioned previously, manumission was never reversed as the idea of re-enslavement was odious to 18-19th century sensibilities (partly why Dred Scott was so incendiary to most people). Also, to claim "racism" ignores that the vast majority of northern immigrants (Irish and German) had little "racial" in common with most northerners. Hence the desire to send hundreds of thousands to kill each other. The modernist historian fights this battle with slavery being the most important thing to the South despite few besides Stephens and some rabid folks caring about it. Also, ignores the absolute hatred of the Planters and the overseer class. Heard one attempt recently to square the circle by claiming Genovese was racist. Genovese as neo-agrarian? God help our academy...

Economically "what ifs" are detailed extremely well by Brian Schoen's book, "The Fragile Fabric of Union." He details the attempts to create merchant banking between the UK and the South to bypass NYC and Boston. The concern of that point reminds us that NYC attempted to secede from the Union during the Civil War.

As regards the North, may I be so brash to suggest that I think Dr. Brands might be overlooking the potential immigrant unrest after a losing war. Think of the inability to potentially bury dead ("This Republic of Suffering" in Reverse) for these poor veteran families. The Michael Walsh (Wilentz discusses him in detail in Chants' Democratic, yet a forgotten voice post Civil War) ethos of workers plight being worse than the slave now has a key data point with a harmonious South/gradual emancipation, and factory workers' bodies rotting throughout the South. Perhaps the industrial labor strife accelerates. Perhaps the Irish do not join the Union army in droves for the push West. Do the Indian Wars succeed without the Irish? Does the reconstituted South with a strong merchant banking system out of Charleston to the world purchase the rights to some Western territories? Does an independent NYC become closer aligned to the UK? Interesting questions to ponder for sure.

Thank you for the post.