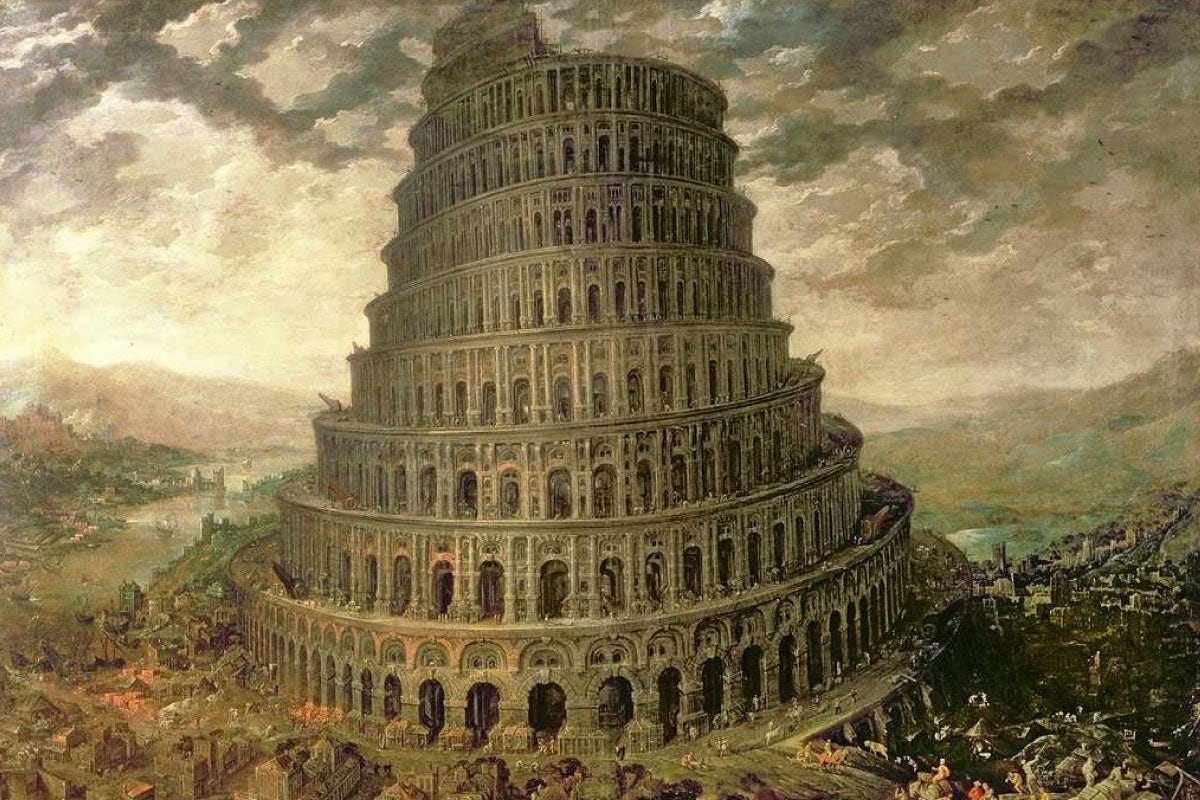

Human Babel

Feature or bug?

"And the whole earth was of one language, and one speech."

So begins the eleventh chapter of the book of Genesis. The next eight verses explain the origins of the multiplicity of human languages. The speakers of the single language got proud and decided to build a tower to heaven. God grew annoyed at their presumption. "Let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech." He did, and people have been speaking many languages ever since.

Modern anthropologists and linguists differ with the biblical version on details but most agree with its premise that human languages evolved from one to many. Yet they disagree with the authors of Genesis on the mechanism. It wasn't an irked God deliberately making languages different but accidental mutations in pronunciation and usage that took hold over time in populations separated by geography or culture.

However they originated, the thousands of human languages are one of the most striking features of life among homo sapiens. For most of the history of our species, the number of languages was growing, as humans colonized new niches.

For the last few centuries, however, the number has been shrinking. Societies aren’t as isolated from each other as they used to be, and their differences tend to erode.

Linguists and others lament the loss of languages. With each language that disappears, a slice of the human experience vanishes.

There’s definitely something to this argument. Yet there's a flip side to the story. The purpose of language is to communicate. And communication is easier when people speak the same language. The fewer the languages, the more likely people will speak the same one.

In some realms of human activity, monolingualism is mandated. Air traffic controllers around the world default to English. Midair misunderstandings can have fatal consequences.

Even where it is not required, a common language is a convenience. It facilitates commerce, government, science and other important parts of life. These advantages are what produces the selective pressure that causes less-used languages to die out.

It's not hard to imagine the trends of recent centuries continuing until humans all speak a single language, or perhaps one of a few. At which point we will be back to the start. Will God step in again and restore Babel? Will language mutate and differentiate as it did long ago? Or will the single language constitute a stable equilibrium that lasts indefinitely?

To predict what God will do is presumptuous—the sort of thing that got the tower-builders into trouble. Better not to go there. Another round of accidental mutation and differentiation seems unlikely, given that human populations are not separated from each other the way they once were. A stable equilibrium seems the likeliest outcome.

But not a necessary outcome. A metaphorical reading of Genesis might substitute human pride for God in causing languages to diverge. Perverse humans had their own reasons to speak differently.

Communication isn’t the only purpose language serves. It marks out different groups. Sometimes this is done quite consciously. Teenagers are constantly devising new slang to confuse their parents. Individuals engaged in a common activity speak in jargon that sets them apart. The Gileadites—in the book of Judges—distinguished themselves from the Ephraimites by the inability of the latter to pronounce the word shibboleth. Scores of thousands of Ephraimites were slain for hissing when they should have been shushing.

Language has been a point of nationalist pride. Nationalist groups emphasize the languages that set their people apart: Catalan and Basque in regions of Spain; Irish (Gaeilge) in Ireland; Hawaiian in Hawaii; Ukrainian (not Russian) in Ukraine; and many others. The founders of Israel reached two millennia into the past to make Hebrew their country’s language.

On balance, the forces that lead to the loss of languages are still greater than those pushing back. A century from now there almost certainly will be fewer languages than there are today. But we’ll probably never get to just one. A little Babel seems built into the human soul.

There can be no question that commerce and political union tend to favor the Big Languages and marginalize other "little" languages such as Scottish Gaelic, Irish Gaelic, Navajo , Quechua, etc. I think mankind has a tendency towards monolingualism. Certainly nationalists, almost invariably, favor one official national language. So I do not believe a little Babel is bulit into the human soul.

Quite the contrary. One has to invest in and work at maintaining a bilingual household or to encourage polyglotism.

However, a healthy bilingualism is possible over a long term: Switzerland is a good example. Canada (English and French) is another. The United States seems to be permanently bilingual Spanish/English in some regions. Another example would be Israel (Hebrew and English). But I would say that Israel did not have to reach into the past to revive Hebrew. Hebrew has always been a language that has been studied and spoken aloud. In modern times it merely replaced Yiddish or Ladino. But we recall Yiddish and Ladino were often written with Hebrew characters.

However, Official bilingualism, as it is called in Anglophone Canada, detracts from multiculturalism because it unfairly prioritizes French over other minority languages. Scottish Gaelic is still spoken in Nova Scotia but has diminished greatly since 1900 and has had little government support. The same is true for Canada's indigenous languages.

But French like English is a Big Language or culture language not unlike Latin or Greek in their time.

St. Patrick could (probably )speak at least two Celtic dialects -Old Irish and British) but he wrote almost exclusively in Latin.

Why? Because Latin was a "Big Language" or culture language in a way Irish Gaelic was not. So historically Big Languages (languages that are commercially or culturally important) are more likely to be a Koine or lingua franca) and so therefore much more likely to survive over a long period of time.

Italian is a lesser BIg Language and so is German BUT both these languages are such powerful cultural languages (with a vast literature and musical culture) that their songs will be sung for centuries all over the world. Arabic, Chinese, Portuguese all seem to have a guaranteed future.

I have been a student of languages all of my life and now in retirement I am studying Modern Greek and Ancient Greek as well as reading Latin every day. Most of the languages I study have strong associations with literature, poetry and song. I have read most international literature in translation, of course, but when I have read poetry or songs in their original I know that translations are not sufficient so I try whenever possible to study bilingual texts and the original versions.

Each language is indeed God's work of art. Official bilingualism may not be possible everywhere but I think language studies are very important for everyone and that we should respect the cultures and languages of others.

As someone with both an M.A. and Ph.D. in linguistics (UT Austin 1964 and 1974, respectively), I found Brands' and Munro's discussions fascinating. Let me share a humorous story which was a segment on the CBS Evening News several decades ago. The story was about a scholar in Israel who was trying to increase the use of Yiddish there. However, even his own children didn't want to learn it, preferring to answer in Hebrew when dad spoke in Yiddish. The reporter asked the father "why are you so insistent on your kids learning Yiddish?" He replied: "So they won't forget they're Jewish." In other words, he considered Hebrew to be the language of the secular state of Israel, whereas for him one felt one's "Jewishness" only through the medium of Yiddish.