Two weeks ago, the world’s thinkers on international affairs were wondering what happened to Ukraine’s counteroffensive against occupying Russian forces and whether the budget follies in Washington would diminish American support for Ukraine. This week it’s all about Israel’s war against Hamas and what it means for the Middle East and the larger world. Will it scuttle the Israeli-Saudi peace deal the Biden administration has been pushing so hard? Will Vladimir Putin exploit the distraction of America to commit some new crime? Will Xi Jinping move against Taiwan?

The coincidence of these concerns raises a fundamental question of international affairs: How do longstanding conflicts end? The one between Israel and the Palestinians goes back 75 years to the founding of Israel in 1948. Yet it has roots far deeper. The Zionists who created modern Israel traced their land claim to the covenant given by God to Abraham. The Palestinians assert possessory rights of comparable vintage.

The struggle between Russia and Ukraine dates from the 2014 seizure of Crimea and eastern Ukraine by Russia. But before that, Ukraine was forcibly folded into the Soviet Union in the 1920s. And before that, Ukraine was bounced between the Russian empire and the Polish and Habsburg empires.

The Taiwan issue dates to the 1940s, when the losers of China’s civil war took refuge on Taiwan and talked America into protecting them. But China’s desire to reclaim control of Taiwan is a half-century older, originating in the seizure and occupation of Taiwan by Japan, which ruled it until the end of World War II.

In an earlier era, when one country or people conquered another, the conquerors often had little compunction about killing, expelling, enslaving, absorbing or otherwise subjugating the conquered. Wars could end definitively, in results that lasted centuries.

One of the clearest examples comes from America history. Euro-Americans fought American Indian nations for nearly 400 years before the war for America ended in the late 19th century. Large numbers of the Indians died, mostly from introduced diseases to which they had little resistance. The outcome was as definitive as the outcomes of wars ever are. Territory remaining under Indian control was a very small fraction of the territory they had occupied when the first Europeans arrived. And even that control was circumscribed by the laws of the United States. Indian populations have revived since their nadir, but there is no prospect the tribes will ever regain what they once called their own.

This outcome inspired a response by British foreign secretary Ernest Bevin to American complaints that the British in the 1940s weren’t treating the people of India well. Bevin refused to be instructed about Indians by the Americans. "We know what you did to your Indians," he was reported to have said.

These days genocide and ethnic cleansing are frowned upon. The modern version of the Carthaginian peace—named for Rome's destruction of Carthage after the last of the Punic wars—was the draconian settlement imposed on Germany after World War I. But this was draconian only in economic terms, and it wasn't long enforced. It sowed resentment in Germany rather than the salt Rome sowed in Carthage, and within fifteen years Hitler had burst its bounds. After World War II, victorious America did not simply not destroy Germany and Japan but underwrote their reconstruction.

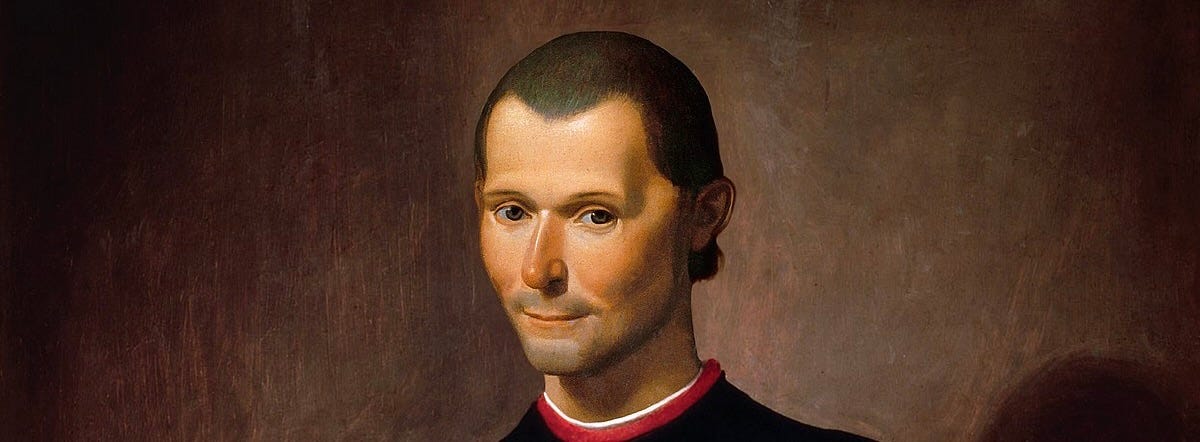

The world wars, however, aren’t good models for stubborn conflict. The belligerents accepted the existence of one another as sovereign states, and this acceptance set limits upon the treatment of the losers. Smaller conflicts—like that between the Israelis and the Palestinians—are a better test. When two peoples fight over the same land, the fight can go on and on. Machiavelli understood the dynamic. “Above all he must refrain from seizing the property of others,” the Italian philosopher and historian said of the wise prince, “because a man is quicker to forget the death of his father than the loss of his patrimony.” Everyone dies, and each death eventually fades into the background of memory. Moreover, a dead father can’t brought back to life. A stolen patrimony, by contrast, especially if it is land, persists. Generations pass, but the land remains. And to those with ears appropriately tuned, it cries out for redemption.

The leaders of China understand the problem, and they have taken—and inflicted—great pains to neutralize it. The civil war in China had scarcely ended when the victorious Communists sent troops into Tibet, and ever since, China’s policy has been to replace that country’s culture with Chinese culture and to swamp its population with Chinese people. Something similar has been happening in Xinjiang, where Uyghur culture and people have been suppressed in a campaign of sinification. The land will remain, but the people will be changed, eliminating any separatist or revanchist feeling. At least that’s the plan.

Taiwan is a different story. The culture there is already Chinese, the indigenous Taiwanese having long since been as marginalized as the indigenous peoples of America were. The conflict over Taiwan is really a civil war among Chinese, comparable to the effort of eleven American states to create a country of their own in the 1860s. Should the Chinese of the mainland extend their control over the Chinese of Taiwan, that conflict will probably come to an end. American Confederates told themselves after their defeat that the South would rise again, but they never acted on their boast.

Yet time matters in the Taiwan case. It wasn't very long ago that the government on Taiwan maintained the fiction that it was the legitimate government of China. This assertion played into the hands of the mainland government, in terms of the cultural cohesion of China and Taiwan. In the last couple of decades, however, more and more voices in Taiwan are calling out for independence. The longer they are allowed to speak without effective rebuttal from Beijing, the more difficult the task of reunification will be. Beijing is aware of this, and has stated firmly that the status quote cannot persist forever.

Ukraine shows what happens when a new status quo is allowed to persist. Ukraine became independent of Russia in 1991 largely as a result of events internal to Russia, not because of heroic independence efforts by the Ukranians. But during 30 years of independence, many Ukrainians developed a national consciousness they hadn't felt before. Now they are fighting heroically for their independence. Whether they will be able to sustain their independence remains to be seen, but China's leaders are surely paying attention to the Ukrainian struggle as a cautionary example of what happens if reunification is delayed too long.

Working in the Ukrainians' favor is the fact that the Russians always have the option of calling off the war and going home. Putin might lose face, but the existence of Russia is not in danger. Likewise for the people and government of Taiwan. China will not be threatened in any strategic way by the mere existence of an independent Taiwan. The significance of Ukraine to Russia and of Taiwan to China is chiefly symbolic. Symbols matter, but they don't have to be deal-breakers.

The fight between the Israelis and the Palestinians looks more intractable. Neither side has any fallback homeland. A two-state solution would leave angry people on each side claiming their land had been stolen from them. Machiavelli would have advised his prince to steer clear of such a struggle.

On the other hand, Ernest Bevin might have pointed out that India and Pakistan were separated by methods short of those America applied to its Indian problem. To be sure, millions died in the partition of the subcontinent. But with the principal exception of Kashmir, India and Pakistan no longer claim each other's territory.

Maybe there is hope for Israel and Palestine after all.

Thank you so very much for your expertise and insight which I feel offers both hope and perspective. Bill Rusen

This ignores the fact that, while in any other conflict mentioned the goal at worst is to destroy a culture and assimilate the people into their culture, in the case of Israel/Palestine, the leaders of one side have the ultimate goal of wiping the other side off the face of the planet as a people. That makes this conflict fundamentally different than any other conflict you've mentioned. It's a religious war.