How much pluribus? How much unum?

Franklin on assimilation

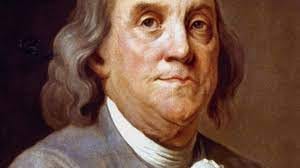

Benjamin Franklin was an open-minded and tolerant fellow, not least because he had benefited from the open-mindedness and tolerance of those who had founded Pennsylvania as a refuge for Quakers and other dissenters from orthodoxies in England and elsewhere. Philadelphia had accepted Franklin as a runaway from Boston and its Puritan theocracy, and he had thrived there as a questioner of most conventions.

Yet Franklin found his tolerance tested when he observed the habits of German immigrants to Pennsylvania. Not that their work ethic left anything to be desired—unlike immigrants from England, Franklin’s ancestral home. “When any of them”—the English immigrants— “happen to come here, where labour is much better paid than in England, their industry seems to diminish in equal proportion,” Franklin observed in a 1753 letter to an English friend. “But it is not so with the German labourers; they retain the habitual industry and frugality they bring with them, and now receiving higher wages, an accumulation arises that makes them all rich.” This spoke well for the Germans.

What did not speak well was the language the Germans spoke, as a consequence of their refusing to assimilate to the existing English-speaking population. “Few of their children in the country learn English,” Franklin remarked. “They import many books from Germany; and of the six printing houses in the province”—Pennsylvania— “two are entirely German, two half-German half-English, and but two entirely English. They have one German newspaper, and one half-German. Advertisements intended to be general are now printed in Dutch”—German (from Deutsch)—“and English; the signs in our streets have inscriptions in both languages, and in some places only German.”

German was displacing English in the courts of Pennsylvania, Franklin said. “They begin of late to make all their bonds and other legal writings in their own language, which (though I think it ought not to be) are allowed good in our courts, where the German business so increases that there is continual need of interpreters.

The Germans were making their presence felt in the politics of the colony. “I remember when they modestly declined intermeddling in our elections,” Franklin said, “but now they come in droves, and carry all before them, except in one or two counties.” The need for interpreters would spread beyond the courts. “I suppose in a few years they will be also necessary in the Assembly, to tell one half of our legislators what the other half say.”

Franklin worried what this would mean for life in Pennsylvania. “Unless the stream of their importation could be turned from this to other colonies . . .” he said, “they will soon so outnumber us that all the advantages we have will not be able to preserve our language, and even our government will become precarious.”

Franklin didn’t dislike Germans per se. “I am not against the admission of Germans in general, for they have their virtues,” he said. “Their industry and frugality is exemplary. They are excellent husbandmen and contribute greatly to the improvement of a country.”

What he disliked was the Germans’ insistence on creating a separate society within the larger English society. This could only bode ill for the cohesion of the existing English society in Pennsylvania.

To forestall such an outcome, Franklin proposed a solution in three parts. “Distribute them more equally; mix them with the English; establish English schools where they are now too thick-settled,” he said. This would produce the best solution of all, one that captured the benefits of the Germans’ frugality and diligence while avoiding the costs of their tendency to self-segregate.

If Franklin were writing in 2022, he might be accused of indulging in a variant of the “great replacement theory,” which asserts that the existing population and culture of America are at risk of being supplanted by immigrants who look and act differently. The extreme version of the theory posits a liberal conspiracy to encourage the immigration of people of color against the interests and future of white Americans. This version appeals to white nationalists looking for an excuse to blame liberals and non-white people for the things they don't like; it appears to have fueled the mass shooting of black people in Buffalo earlier this month.

Yet Franklin was no extremist, and the fact that he was complaining about Germans—a group about as close racially and culturally to the English as any group could be—shows that concerns about assimilation have roots that run deep and transcend race.

Franklin didn’t get his way; no policies were implemented to compel the Germans to spread out. In fact, what happened with the Germans was what happened with every other group of immigrants to America. Their children and grandchildren eventually assimilated, and American society carried on.

The worries never went away. After the Germans it was the Irish who seemed unassimilable. And then Italians and Poles and Russian Jews. And Chinese and Japanese. And Vietnamese and Mexicans and Central Americans and Haitians. Each was portrayed as being more different than the previous ones and therefore less assimilable. The fearmongers included the Ku Klux Klan, the Know-Nothing party, the California Workingmen's party, the John Birch Society and present-day white nationalists.

But the worriers were not all extremists. Change is upsetting to many people. And it’s not unnatural to worry that newcomers who bring different experiences and values to the United States might jeopardize the values that have made the United States successful. The future of self-government isn’t guaranteed. Franklin, the soul of reason, worried.

When the Continental Congress adopted the motto E pluribus unum—From many, one— it was referring to the thirteen states that came together to form one nation. Over time, the phrase was applied to the many different groups who came to America and formed the American people.

The challenge was always to find the right balance between the many and the one. So far we’ve managed pretty well. Very likely we will continue to do so. The extremists have always gotten it wrong, and there is no reason to think their losing streak is about to end.

Once again, a great post. Once again, however, I am lured away from the headline baiting post (I completely missed the Rockefeller one), and think about the ideas of Franklin and later what is an American identity. The policies and rhetoric to achieve those things are always filled with compromise and opportunity. Let the poli sci Phd.'s play academic buzzword games for those (Tocqueville, Engels, Strauss, Bingo!) impressed by their golden words. It would be interesting to think what Aquinas or Augustine would think about the chase for "trends" and "retweets."

Today's West is influenced by the lack of introspective doctrine on the above question. When the Cold War began, America was religion to the Communist godless, markets to the command economy, etc. This fight for ecumenism to unite against a clear enemy created good bedfellows (Anti-Catholic sentiment disappeared in the US a generation after Blaine amendments spread across the nation) and strange ones (Coca cola's expansion and profits is the American way!). The results of this American "ecumenism" was laid bare in 1978 when Solzhenitsyn approached the dais that fateful Spring day in Cambridge...

Attempts to find unity dilute what previously was an important identity. These two forces continually fight each other in the quest for compromise. Identifying what must not change has to start with the good old Chestertonian fence.

I would add that the great replacement theory is about importing Hispanics folks because they will vote for Democrat candidates. I don't see any xenophobia in it. (I could be wrong.) It is a simplistic prediction of the future that is almost guaranteed to be wrong. Even today, the Hispanic population is shifting away from the Democratic Party.

Another great post, Professor Brands. Thank you.