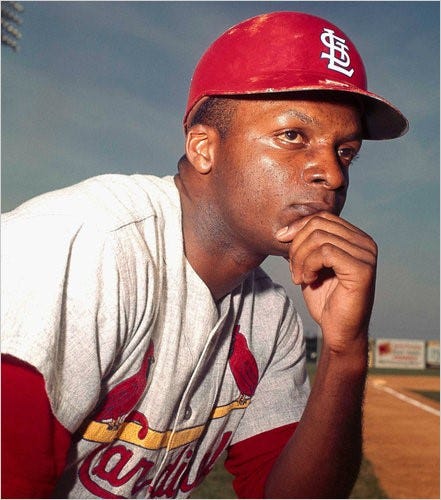

In 1972 baseball was still the American national pastime. Curt Flood knew this; so did Harry Blackmun. Flood was thirty-four years old and had played center field for the St. Louis Cardinals for twelve seasons. He batted and threw right-handed and had won the Gold Glove award for defensive excellence seven times, besides playing in three all-star games and twice helping the Cardinals to victory in the World Series.

Harry Blackmun was sixty-four years old, and had played associate justice for the Supreme Court for two years. Blackmun was a switch-hitter, sometimes writing left, as in the case of Roe v. Wade, to be decided the next year, and sometimes right. He was also a huge fan of baseball. “It is a century and a quarter since the New York Nine defeated the Knickerbockers 23 to 1 on Hoboken's Elysian Fields June 19, 1846, with Alexander Jay Cartwright as the instigator and the umpire,” he wrote for the benefit of Curt Flood and other interested parties. “The teams were amateur, but the contest marked a significant date in baseball's beginnings. That early game led ultimately to the development of professional baseball and its tightly organized structure.”

No detail escaped him. “The Cincinnati Red Stockings came into existence in 1869 upon an outpouring of local pride. With only one Cincinnatian on the payroll, this professional team traveled over 11,000 miles that summer, winning 56 games and tying one. Shortly thereafter, on St. Patrick's Day in 1871, the National Association of Professional Baseball Players was founded and the professional league was born. The ensuing colorful days are well known. The ardent follower and the student of baseball know of General Abner Doubleday; the formation of the National League in 1876; Chicago's supremacy in the first year's competition under the leadership of Al Spalding and with Cap Anson at third base; the formation of the American Association and then of the Union Association in the 1880's; the introduction of Sunday baseball; interleague warfare with cut-rate admission prices and player raiding; the development of the reserve ‘clause’”—and on and on.

Blackmun might have stopped there, for the case before him and the court—the case brought by Curt Flood—turned on the reserve clause. After Flood’s dozen years with St. Louis, the Cardinals’ management informed him that he had been traded to Philadelphia. Flood didn’t want to leave St. Louis, and he especially didn’t want to play in Philadelphia. Flood was a black man, and Philadelphia had a reputation for racist fans. Flood thought he and other major-league baseball players should not be required to move from one team and city to another at the whim of the team owners. As he put it in a letter to Bowie Kuhn, the commissioner of major league baseball, “After twelve years in the Major Leagues, I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several states.”

Kuhn disagreed. The commission of baseball served as the agent of the team owners, who since the nineteenth century—as noted by Justice Blackmun—had benefited from the reserve clause. Players received annual contracts, which included a clause reserving to the teams the exclusive right to the players’ services for the following year. A player could not shop his services around to the highest bidder, as nearly every other employee in America could do as a matter of course. When players were traded, often without their consultation, the reserve clause bound them to their new team. In theory, a player might sit out a season, playing for no team at all, and then seek a new employer. But a professional athlete’s career is typically short, and few players felt they could afford the lost salary. And because the teams judged it in their interest to maintain a solid front on the reserve clause, they would often refuse to hire a player who tried to circumvent the clause by sitting out.

This was the system Curt Flood wanted to change. The case of Flood v. Kuhn reached the Supreme Court in 1972. Public opinion—crucial in a case like this, professional baseball being a form of popular entertainment—was split. Working men and women could sympathize with Flood’s not wanting to be bound to single employer. Yet Flood was a wealthy man by ordinary standards; the salary he refused by not playing for Philadelphia in 1970 was $100,000, twenty times the median family income in America. More than a few fans thought he ought to take the money and shut up.

Harry Blackmun didn’t put the matter so bluntly, but that is what he and the Supreme Court decided. Blackmun acknowledged that the reserve clause gave the teams a monopoly over players’ services, and that this monopoly violated the spirit and letter of American antitrust law. Yet Blackmun, having recited the history of baseball, referred to the episodes of that history—in particular, previous Supreme Court decisions—that exempted major league baseball from antitrust law, on grounds that the business model of the sport required stability in team rosters. “With its reserve system enjoying exemption from the federal antitrust laws, baseball is, in a very distinct sense, an exception and an anomaly,” Blackmun wrote. Baseball’s exceptionalism was a political matter, not a judicial one. “If there is any inconsistency or illogic in all this, it is an inconsistency and illogic of long standing that is to be remedied by the Congress and In by this Court.”

Curt Flood lost his battle. But he won the war. By shining a light on the reserve clause, Flood made it susceptible to change in collective bargaining between the players’ union and the teams. Three years after Blackmun’s ruling, the teams accepted the principle of free agency in players’ contracts. And in 1998, Congress approved the Curt Flood Act, formally revoking the antitrust exemption of major league baseball in most matters.

Free agency produced an enormous increase in players’ salaries, leading in time to multiyear contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars for the best players. Baseball’s stars went from being merely rich to astronomically so.

The man who made it possible never benefited from the change. After refusing to report to Philadelphia, Flood was traded to Washington, where he played less than a month before retiring. He died in 1997, having just turned fifty-nine.

Once again, thank you for an illuminating and interesting essay. Bill Rusen