Candidates for leadership positions don't usually begin their interviews by describing their exit strategies. They should. Good exits are important indicators of successful tenures. When bosses leave in a blaze of glory or even a glow of satisfaction it means their enterprises are thriving and are positioned for further success.

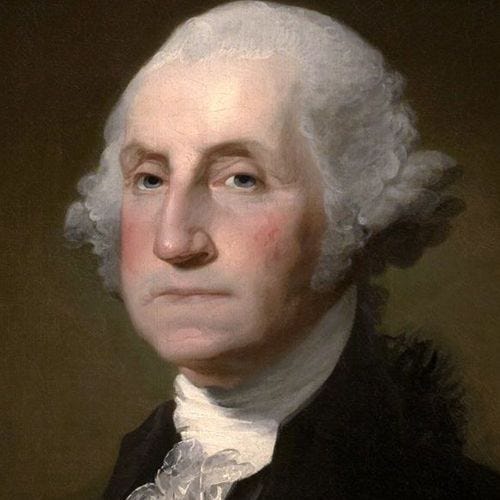

George Washington was thinking of leaving the presidency when he accepted it. Washington didn't want to be president. He was happy with his life as proprietor of Mount Vernon and its farms. He was satisfied with the reputation he had won as commanding general of the victorious Continental Army in the Revolutionary War. Indeed he feared that entering the political world, which was not an area of strength for him, would tarnish the reputation he had won in the military world, which was.

Yet Washington was prevailed upon by men he respected to permit his candidacy for first president under the new Constitution. They said the fledgling republic required his wise leadership. Once he set the ship of state on a steady course he could retire again, this time for good.

Washington won the vote of every elector, to no one's surprise, and took the oath of office at Federal Hall in New York, which served as the seat of government at that time. He formed his cabinet. He signed numerous laws creating federal agencies. He looked forward to the end of his four-year term as the end of his political career.

His eagerness to leave was made all the stronger by dissension that wracked his administration. His principal advisers, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, held opposite views of the purpose of government. Jefferson wanted government lean and unobtrusive, while Hamilton insisted that it be obvious and powerful. Their quarrel spread beyond the administration to the country at large and produced opposing parties, the Republicans and the Federalists.

Washington distrusted parties as undermining the civic spirit he thought essential to the survival of the republic. He chided Jefferson and Hamilton for their roles in producing the rift. He wondered why he had let himself be talked into entering politics. More than ever he looked toward the day he could leave the odious realm.

Jefferson and Hamilton didn't agree on much, but they both believed that Washington remained essential to the country's salvation. Each hoped Washington would talk sense into the other. Each pleaded with him to remain for a second term.

The same sense of duty that had prompted Washington to enter politics in the first place caused him to accept a second time.

But his second term was more frustrating than his first. War in Europe pulled the Republicans and the Federalists in opposite directions and caused party each to impugn the patriotism of the other. Washington leaned toward the Federalists in philosophy without embracing their partisan cause. For this the Republicans condemned him as a would-be monarch: King George I of America.

Washington finally said enough was enough. He bade farewell to the American people and in going gave them a lecture on how not to conduct themselves. They must not let attachment to party displace their attachment to their country. They must not let preference for one foreign country over another distract them from the interests of America. They must not lessen their devotion to the fundamental task of perfecting American self-government.

Washington made no effort to influence the choice of his successor. Vice President John Adams, a Federalist, defeated Republican Jefferson in a close race. At his inauguration, Adams couldn't miss the relief in Washington's demeanor. “He seemed to enjoy a triumph over me,” Adams wrote to his wife. "Me thought I heard him think, Ay! I am fairly out and you fairly in! See which of us will be happiest.”

The full importance of Washington's departure wouldn't become apparent until he died three years later, during what would have been his third term. Had Washington accepted a third election and died on the same schedule, he would have established an expectation that presidents would serve for life. The Constitution did not forbid it. Some of the Constitution's framers, most notably Hamilton, hoped the presidency would indeed be a life office.

Washington wanted no such thing, and he got out just in time. Instead of establishing a precedent of life tenure, he established a precedent of two terms and no more. So exalted was Washington's reputation and so powerful his example that the de facto two-term rule remained in force until 1940, when it was broken by Franklin Roosevelt. Even then, Washington's influence was sufficiently strong that a consensus quickly emerged that the Washington rule must be written into the Constitution, as it was by the 22nd Amendment.

Had Washington not walked away when he did, the tenor of subsequent American politics would have been dramatically different. Presidents would have been tempted to cling to power as long as life. Presidential elections would have become even more acrimonious than they did, on account of a perception in voters that they were choosing someone not for one term or two but for life.

The takeaway for leaders of any sort of enterprise is to keep in mind that the enterprise will last longer than you. Be thinking of your exit even as you enter the job. You will be remembered for your tenure but also for your departure and what you left behind.

“The takeaway for leaders of any sort of enterprise is to keep in mind that the enterprise will last longer than you.”

The best leaders’ best hope should be that it will.

I don’t know if you have an opinion, but I really think the immorality of Jefferson’s subterfuge while working with Washington was underplayed in Art of Power. I kept thinking to myself—how could he do that? How could he speak out of both sides of his mouth to Washington, for one, and also undermine the stability of the new government?

All that being said—I respected the way he conducted his presidency.