From 1850 to 2025

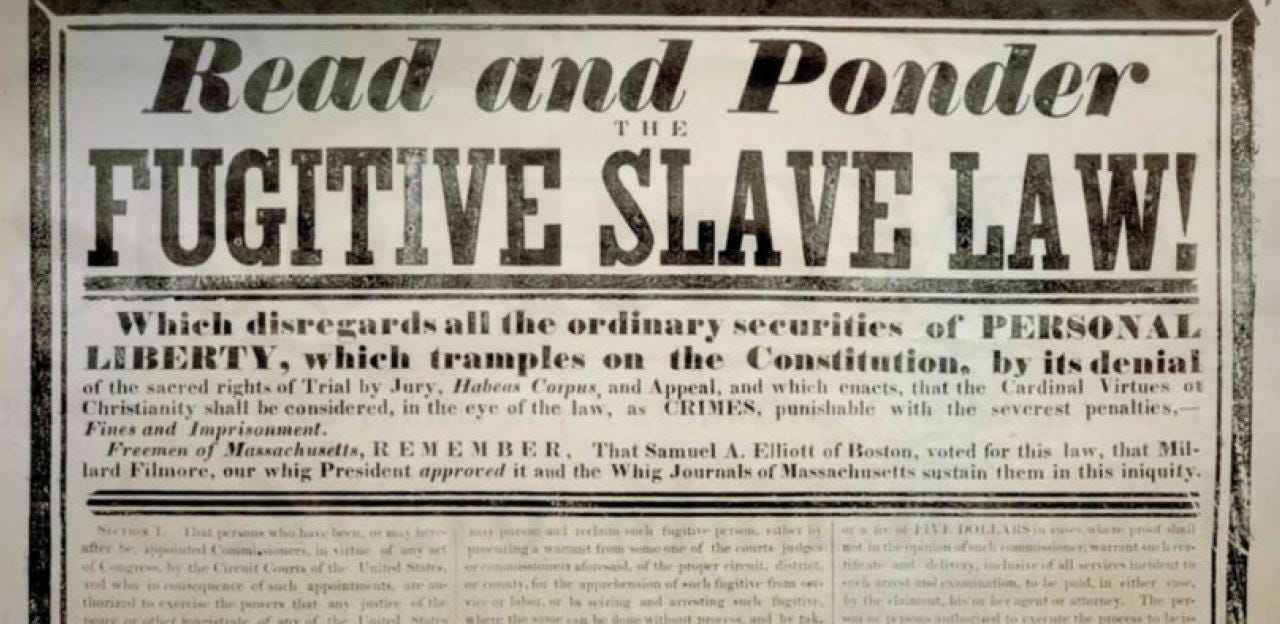

Trump and the Fugitive Slave Act

Donald Trump will be inaugurated for the second time in early 2025, the 175th year after passage of the Compromise of 1850. He has pledged to implement policies that seem likely to revive controversies aroused by that provocative piece of legislation.

The 1850 law was prompted by California’s request for admission to the Union. Californians had written a constitution forbidding slavery, in keeping with their opposition to that institution. The southern bloc in the Senate objected, as California's admission would tip the balance in the upper house in favor of the free states. Southerners demanded a quid pro quo: a strengthened fugitive slave law, which would stanch the flow of escaped slaves to the north. A deal was struck. The north got California, the south got the Fugitive Slave Act.

Antislavery opinion in the north was outraged. The new law required the cooperation of authorities in northern states in the capture and return of fugitive slaves. Many northern states had passed personal liberty laws forbidding such cooperation. These laws were presumptively unconstitutional, in that they violated the clause of Article IV that required the return of any “person held to service or labor” to the state from which such person had fled. But the laws hadn't been successfully challenged.

The Fugitive Slave Act did precisely that. Northern sheriffs and judges found themselves dragooned into the ranks of slavecatchers. Many complained on moral grounds. Others resented what they took to be southern arrogance in compelling northerners to bow to odious southern practices.

President-elect Trump's proposal to deport millions of undocumented immigrants will raise similar objections. Several states have declared themselves sanctuaries for undocumented immigrants. By state law or executive pronouncement they’ve pledged not to enforce federal immigration laws. More than a hundred cities and counties have taken similar positions.

Enforcement of the 1850 act triggered widespread civil disobedience in the northern states. Opponents of slavery mobbed slavecatchers and kept them from their unsavory though legal business. The “underground railroad”—the system of sympathizers and safe houses that aided escaped slaves—stretched to Canada, beyond the reach of the new law.

Southerners seethed at this patent nullification of federal law. It contributed to their growing belief that their states’ constitutional right to slavery would never be safe under a Union government controlled by enemies of the institution. When, ten years after passage of the fugitive law, the north elected Abraham Lincoln president on an antislavery platform, eleven southern states bolted the Union. The Civil War ensued.

A second civil war isn’t likely to follow enforcement of Trump’s pledge to deport undocumented immigrants. The fault lines in America today run through states, between cities and rural regions, as much as between states, as they did in 1860.

But a massive sweep against the undocumented will raise similar issues of jurisdiction and control. There aren’t enough federal enforcement officers and federal detention facilities to accomplish what Trump has promised. Any federal sweep will require state and local support.

And it will require that support in precisely the places where it will be given most reluctantly. The sanctuary states and cities tend to be the places with the largest numbers of undocumented immigrants. Locals don’t have to actively oppose the sweeps to stall them. They merely have to move slowly in supporting them.

Possibly Trump is aware of this prospect and welcomes it. He likes to provoke. If he can cast blue states and cities as violators of federal law on an issue that helped elect him, he might deem the deportation effort a win regardless of how many people are actually expelled.

By no means were the resisters against the 1850 fugitive law universally honored in the north. Many northerners condemned them for making a civil war more likely. Only in retrospect, after emancipation caused their antislavery activism to appear prescient, were they generally seen as being on the right side of history.

There’s no telling how Trump’s deportation effort, if he actually follows through on his campaign promise, will be viewed by history. If it leads to an enduring solution to America’s immigration problem, it might well be judged a stern but necessary step in the right direction. If it merely aggravates the polarization of American politics, it will be seen in a less favorable light.

I think a far closer analogy to the Fugitive Slave Act is not migrant deportation, which we have had mass deportations a couple of times already under FDR and Eisenhower for example.

No. A closer analogy to the Fugitive Slave Act will be when the Trump Administration enacts Project 2025 and it's attack on reproductive rights kicks in.

P2025 calls for the federal Dept of Health and Human Services to require states, on pain of losing federal dollars, to report to the DHHS the names and home addresses of women who get abortions in states where it is legal. The DHHS can then send those names back to anti-abortion states like Texas to prosecute the women when they return home.

This is a close analogy in which federal law would force people in "free states" to states to be compelled to support a "peculiar institution" - i.e. preventing women from getting necessary medical care.

Muchissimo gracias.

I use history to explore what we shall become, knowing who we are, and by learning from where we have come.

An insightful nugget in today’s essay: “A second civil war isn’t likely to follow enforcement of Trump’s pledge to deport undocumented immigrants. The fault lines in America today run through states, between cities and rural regions, as much as between states, as they did in 1860.”