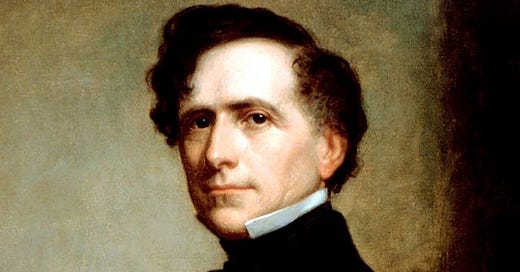

Franklin Pierce. The limits of conciliation

Leadership lessons of the president

A president from a small state like New Hampshire has no large home constituency to rely on. To make a name in national affairs he has to cultivate people from other states and other sections.

Franklin Pierce did this well enough to win the Democratic nomination in 1852. The nomination was tantamount to victory in the election, as the Whig party had blown itself to bits over the Compromise of 1850. Pierce trounced Winfield Scott by 254 to 42 in the electoral tally.

He continued his outreach efforts after inauguration. He populated his cabinet with southerners as well as northerners. The key post of secretary of war went to Jefferson Davis of Mississippi.

Pierce cultivated Congress, to conciliate the sectional factions there. Stephen Douglas of Illinois was the Democratic dynamo in the Senate. Douglas determined to end the debate in Congress over the future of the western territories regarding slavery. His formula was popular sovereignty — the principle of letting the residents of the territories decide for or against slavery when they drafted constitutions to convert their territories into states. What could be more democratic? asked Douglas. What more fitting for the Democratic party?

Pierce initially demurred. Popular sovereignty had two corollaries, he pointed out. First was the overturning of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had barred slavery from the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase. Many northerners would resist this as a surrender to the slave South.

The second corollary would be competition between proslavery and antislavery forces to populate the territories. Each would hasten to get its partisans on the ground ahead of the drafting of the state constitutions. Matters might quickly turn violent.

Yet Pierce worried that taking a stand against Douglas's approach would cause trouble. Sectionalism had destroyed the Whigs, and it might destroy the Democrats. Douglas portrayed popular sovereignty as the last resort of the party of Jefferson and Jackson. It might be the last resort of the Union as well, for if the Democrats split, there would be nothing holding the sections together.

Pierce let himself be persuaded. Popular sovereignty took legislative shape in the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.

He soon had cause to wish he’d held his ground. Many northerners were indeed outraged at this gift to the South. And slavery's advocates and opponents poured into Kansas Territory, with each side trying to discourage, intimidate and sometimes terrorize the other. Proslavery guerrillas sacked the antislavery community of Lawrence. An antislavery gang led by John Brown brutally murdered five proslavery men in a hamlet on Pottawatomie Creek. Newspapers around the country carried lurid stories of “Bleeding Kansas." On both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line editors and other opiners predicted the imminent end of the Union.

The Union survived the Kansas crisis. The Democratic party did too. Pierce’s career did not. Rather than eliciting credit from North and South for averting a worse outcome, his conciliating efforts brought him blame from each section for not delivering more of what it wanted. The Democrats denied him renomination and sent him back to New Hampshire.

James Blaine was from neighboring Maine and came to know Pierce in retirement. "Frank Pierce once told me that God Almighty had permitted no torture to be invented so cruel as the life of an ex-president," Blaine wrote to a friend. Blaine related a comment Pierce had made upon departing the White House in 1857: “There is nothing left for me but to get drunk.”

Which he did. He died of cirrhosis of the liver in 1869.

Great post!

Pierce’s Democrat successor, James Buchanan, was even worse.