War is never fought entirely for money, but rarely is lucre wholly absent from the agendas of belligerents. Washington, Jefferson and many other well-heeled American colonials were constantly in debt to British creditors. It wasn't lost on them that American independence might free them financially as well as politically. A sticking point at the end of the war was whether British creditors would be allowed to pursue prewar debts. The Treaty of Paris said they would but gave no guarantees. It also pledged that the British would return property seized during the war. The Americans got back their immovable property but not such movable property as slaves who had joined the British army to fight against their former masters. These “Black Loyalists" were spirited away by British ships at the end of the war. Following that treaty violation by the British, the Americans saw no reason to fulfill their promise about the debts.

Debt provided grease to lubricate the transfer of California to the United States at the end of the American war with Mexico. It also salved the American conscience. Having seized half of Mexico's territory, the United States agreed to assume debts owed by Mexico to American creditors. This and a modest cash payment allowed the Polk administration to claim that California and New Mexico had been purchased rather than stolen.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, debts were deployed as excuses for gunboat diplomacy. A small country in Asia, Africa or Latin America would fall into debt to Britain, France or Germany. When it got behind in payments, the European powers would send in gunboats, seize the customs houses, and divert the revenues to the European banks holding the debt. From this procedure, permanent occupations sometimes followed. The British occupation of Egypt lasted from 1882 to 1954.

American presidents adopted the technique for their own country. Adding a corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, Theodore Roosevelt warned the British and Germans against employing force to collect Latin American debts. Roosevelt acknowledged that force sometimes had to be used against small countries that misbehaved, but he said that in the Americas it was the United States that would exercise this “police power.” He and his successor, William Howard Taft, monetized the new policy by strong-arming Latin American debtors into borrowing money from American banks to pay off the Europeans. This way American gunboats, and the marines that accompanied them, became debt collectors not for European bankers but for Wall Street.

Debts vexed—indeed cursed—the peace settlement at the end of World War I. That conflict had converted the United States from a debtor nation to the underwriter of the world. Britain and France borrowed heavily from the United States to fund their war efforts. Upon victory, American officials made clear that the debts must be paid. The British and French determined to acquire the wherewithal from Germany, which was saddled with an enormous and open-ended bill for reparations. When Germany in the 1920s proved unable to pay the bill, its government was encouraged—effectively compelled—to borrow American money to cover the shortfall. A triangular trade in dollars resulted. Dollars flowed from America to Germany, then from Germany to Britain and France, and then from Britain and France back to America, with interest accruing en route. The racket was profitable for a while, but it collapsed amid the Great Depression when nearly everybody defaulted on nearly everything, after everyone had become embittered against everyone else.

Generals sometimes learn from the last war; so do presidents. Franklin Roosevelt chose to take debt off the table in relations with America's allies in World War II. The Lend Lease program proved neither lend nor lease. Instead the United States simply gave to Britain, Russia and China what they needed to fight against Germany and Japan. After the war America gave friendly Europeans reconstruction aid via the Marshall plan.

Of course nothing really comes free. To receive the Marshall money, the Europeans had to bury their ancient rivalries and collaborate in what became the Common Market and then the European Union. And they—and other recipients of American funding after the war—had to agree to the liberal principles of free trade American strategists devised to stave off a third world war and allow American penetration of foreign markets.

There's a saying in the world of finance that if you owe a bank a million dollars, you have a problem; but if you owe the bank a billion dollars, the bank has a problem. Sometimes the debts owed to Americans were leveraged against the United States. The Russian revolution of 1917 toppled a czarist government that owed money to Americans. The new Bolshevik regime repudiated the debt, saying that such things were capitalist affairs which socialism transcended. The United States government repudiated the repudiation. It withheld recognition of the Soviet Union. To be sure, the debt wasn't all that stuck in Washington's craw. The communists’ proclaimed desire to overthrow capitalist governments around the world was a bother too. But in the 1930s a bargain was struck. The United States recognized the Soviet Union, and the Soviet government acknowledged the principle of debt repayment. (Getting from principle to practice proved more difficult. The task hadn't ended when World War II began, and the czarist debts were swallowed up in that conflict.)

The use of debt to promote desired behavior continues. Like the atheist revolutionaries in Russia, Islamist revolutionaries in Iran in 1979 disavowed debts owed by their country to the United States and other western powers. The American part of the debt question grew more complicated when Iranian radicals seized scores of American hostages and held them for more than a year. The administration of Jimmy Carter responded by freezing Iranian assets. Eventually an agreement was struck for the release of the hostages in exchange for release of some of the assets and renegotiation of the debts. The renegotiation dragged on for decades, becoming entangled with Iran's support for terrorist groups in the Middle East, its potential for acquiring nuclear weapons, and the seizing of more hostages. The most recent progress occurred last fall, when the Biden administration agreed to release $6 billion in frozen Iranian assets in exchange for the release of five Americans held in Iran.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the United States and the European Union froze hundreds of billions of dollars of Russian assets. A debate has developed over how those frozen assets should be used. Some in Europe and the United States advocate employing the money, or at least interest on the money, to provide support for Ukraine in its war against Russia. Some go further, urging the use of the whole amount for the reconstruction of Ukraine. On the other side of the argument are those who cite history in saying that the prospect of repayment can be a useful lever in resolving larger issues. The money should remain frozen, they say, and be used as enticement to Russia to end the war.

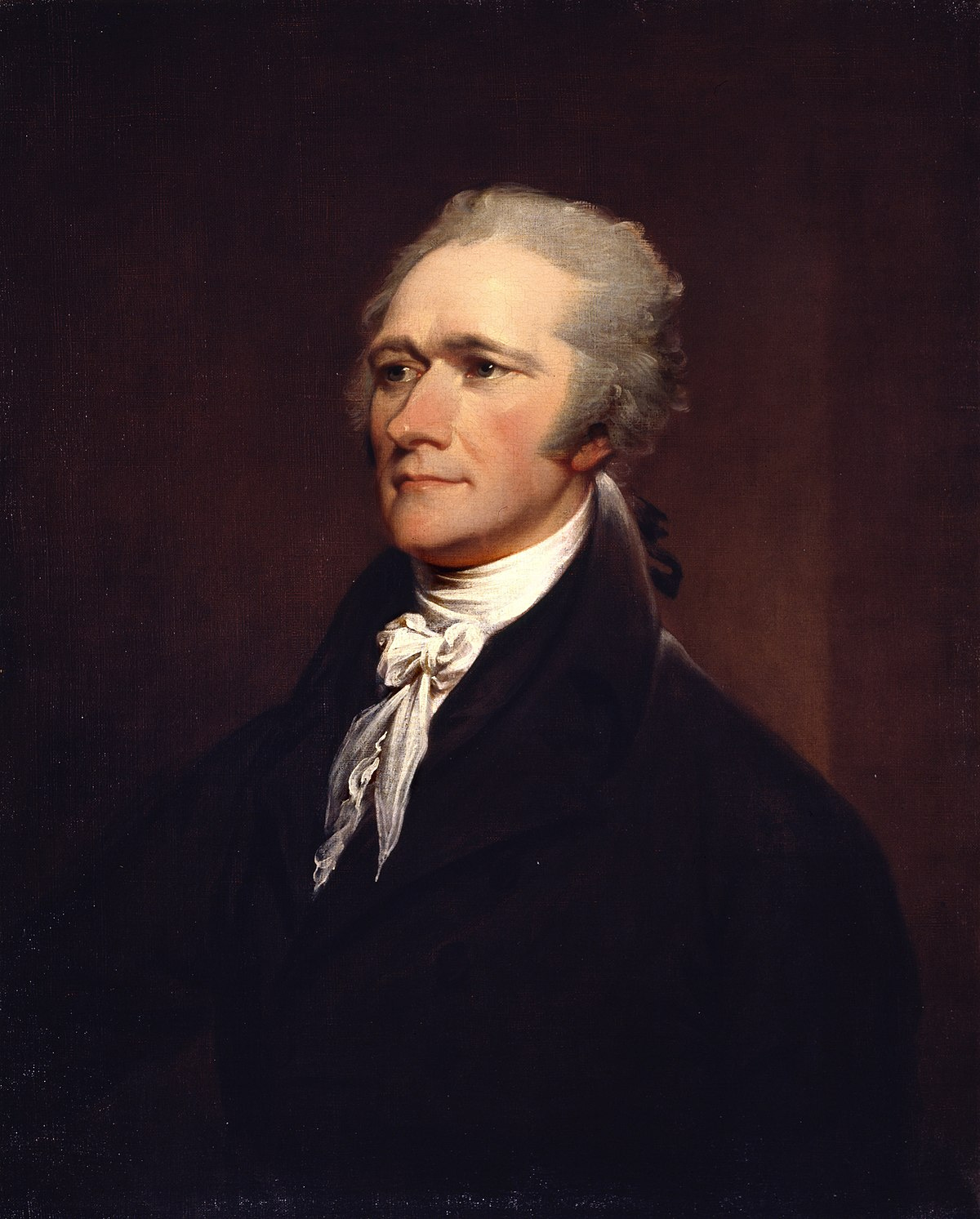

Alexander Hamilton said that a nation’s debt could be a blessing. History has shown that it can also be a sword, with two edges.

Don't forget the poor Haitians debt problem- they literally had to buy their freedom from France in 1825 under conditions such that they couldn't even pay off the principle. France got paid off by the US banks taking on the debt which wasn't paid off fully until 1947! Arguably this debt has hobbled Haiti ever since by never allowing the nation to really get a decent economy going