Exit gracefully

And timely

My father wasn’t happy when I told him I was going to quit the family business and become a teacher. Perhaps he never had a teacher who inspired him, or maybe he simply took his cues from the business culture he grew up in. But his was the philosophy that said that those who can, do; and those who can't, teach. I suppose I might have been flattered that he thought I would be wasting my talents in the classroom; at least he thought I had talents to waste. At the time, I didn’t look on it that way.

I've never regretted my choice of career. Yet I've come to realize that there was an underlying truth in my dad's point of view. It's something that applies to everyone the older we get. However great our accomplishments and in whatever field, there comes a time when our powers begin to decline. We can't do what we used to be able to do. That is, we can't do it ourselves. But if we can teach others to do it, then it will still get done. In other words, we all reach a stage in life where my dad's philosophy kicks in. We can't do, so we teach.

I've been thinking about this in the context of American presidential politics. Odds are that the race this fall is going to be between an octogenarian and a late septuagenarian. I ask myself the same question many others are asking: Why do these two old guys still covet the brass ring? And no less important, why haven't their parties and the American electorate insisted on finding younger replacements?

Both men, I suppose, would say their work isn't finished. After applying an appropriate political discount, I'll grant their sincerity in such claims. But don't they realize the work is more likely to be finished if they identify and promote successors who will carry on after they’re gone?

To be sure, choosing a successor is an uncertain business. Theodore Roosevelt handpicked William Howard Taft to continue the progressive work Roosevelt had begun. Taft in office proved to be less progressive than Roosevelt had thought, and Roosevelt came out of retirement to challenge him. But this actually revealed more about Roosevelt and his egomania than about Taft’s devotion to progressivism.

The corporate world is a better arena for assessing transfers of power, if only because in the corporate world there is a ruthless measure of success: the bottom line. Steve Jobs is often hailed as the prototype of the modern CEO: brilliant, demanding, visionary. No one is more responsible than Jobs for creating the smartphone milieu in which modern living takes place. Yet the best thing Jobs ever did, from the standpoint of Apple Inc., was to choose Tim Cook as his successor. Apple’s value under Cook has increased almost tenfold to three trillion dollars, making it the most valuable company in the world.

The line of succession at Microsoft, Apple's longtime rival, wasn't so straightforward. Founder Bill Gates handed the company off to Steve Ballmer, who missed the transition to mobile computing. But Ballmer tapped Satya Nadella, who after Ballmer's departure recaptured the Microsoft mojo and restored Microsoft to parity with Apple.

Jobs died too soon to see the thriving of Apple under Cook; Gates is still active and presumably proud of what Nadella has done.

Pride in one's proteges comes naturally to teachers. I'm sure I speak for most if not all of my fellow teachers when I say that nothing gives me more professional pleasure than learning about the successes of my former students.

I don’t think politicians feel the same way. Indeed, the evidence points in the other direction. It may be that they're working in an economy with a different currency. The currency of politics is power, and nothing is more jealously guarded than power. Histories of the Roman empire and many other empires and countries are littered with the corpses of competitors to the throne. In America, office holders have learned not to slay potential successors. But the way many of them cling to power lends to the suspicion that some would if they thought they could get away with it.

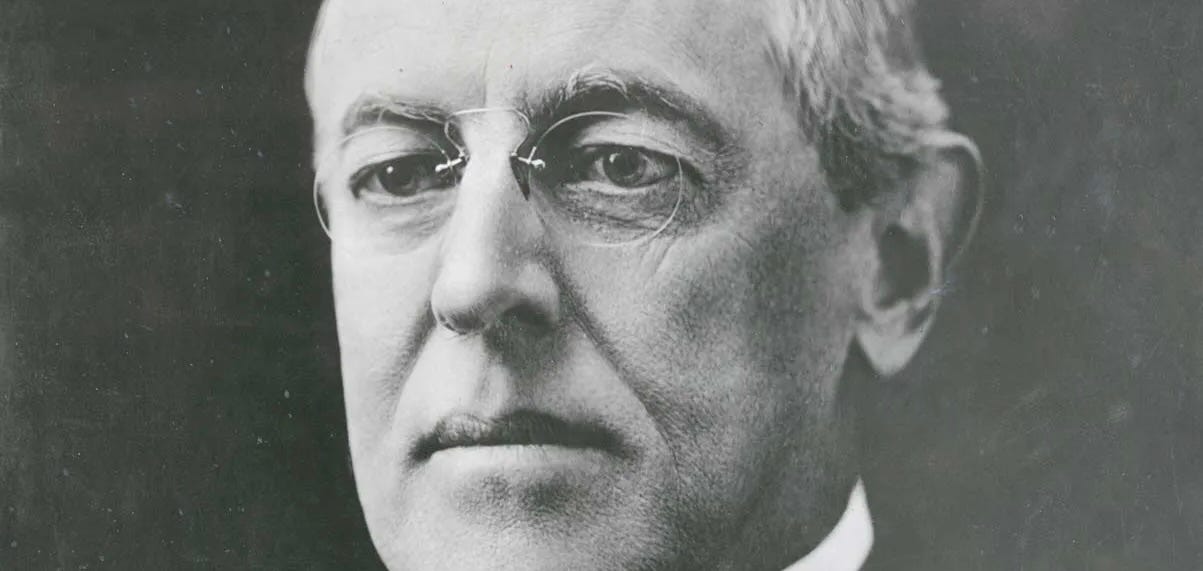

Woodrow Wilson should have been a test case. He remains the most prominent professor-turned-politician in American history. If any president should have been inclined to prepare a successor and step aside, it was Wilson. But Wilson wouldn't let go. Even after his debilitating stroke he imagined that the Democrats would turn to him for a precedent-busting third term. And when the Democratic ticket lost badly in 1920, he deluded himself into thinking he might be called out of retirement for 1924. Death spared him another rejection.

If Wilson couldn’t resist the temptations of power, I suppose it’s unrealistic to expect resistance from today’s politicians. Yet if they did resist—if they took a bow and exited gracefully—their example could be instructive for us all.

I love these essays. They show how history is directly applicable to the world in which we live. I teach very part-time through a state university. I know I can find ways to incorporate these essays into US history. That said, it is my Modern World History Students who are the thinkers. I will look for opportunities there as well.

Do you think the “new” tradition of European Royalty abdicating to a younger generation is significant in regards to today’s essay. Yes, they are constitutional monarchies. However, it might be a good example of giving up power and glory with grace.

So good, sir!