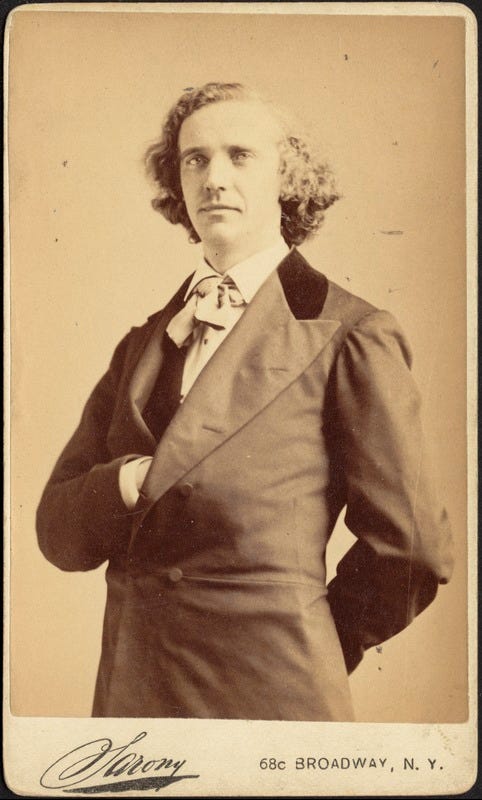

Victoria complements her public letter with a private message. She sends word to the office of the Golden Age, Theodore Tilton’s paper, that she wishes to see him. He has read her “card,” as open letters like hers to the World and Times are called, and deems it prudent to honor her wishes. She hands him a copy of the card. “She asked me to read it,” he recalls later. “I began to read it. She said, ‘I wish you would read it aloud.’” He does so, including the part about an eminent teacher having as concubine the wife of another eminent teacher. She looks him directly in the eye. “Do you know, sir, to whom I refer?” she says.

“How can I tell to whom you refer in a blind card like this?” he says.

“I refer, sir, to the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher and your wife.”

Tilton’s mouth says nothing, but his demeanor speaks volumes.

“I read, sir, by the expression on your face that my charge is true.”

He remains silent, prompting her to recount several particulars of the case. She says she has the story from multiple sources.

Without admitting anything, Tilton departs. He immediately goes to Henry Beecher and Frank Moulton, a mutual friend and confidant. “It was in that way that Mr. Beecher and Mr. Moulton and I came into consultation as to how to treat with Mrs. Woodhull and to deal with her threats to expose the secret between Mr. Beecher and Mrs. Tilton,” Tilton recalls.

Beecher displays extreme agitation, but Moulton tries to calm him. “Mr. Moulton said he did not see what reason a woman could have who didn’t know either Mr. Beecher or myself—who could not be supposed to have any personal enmity against or any interests in us,” Tilton says. “Mr. Moulton said he did not see what motive the woman could have for carrying forward any enmity, and that she needed only to be touched by kindness in order that all the enmity which had thus far exhibited itself in the threat might disappear. His proposition was to treat her with kindness, do some service for her, put her under some obligation to us.”

Beecher sighs with relief. “Mr. Beecher said that he would very cheerfully cooperate in that plan, and he thought it was the best and only plan.” He asks if Tilton will go along.

“I said I would, and we agreed, as part of the method by which we would deal with Mrs. Woodhull, that we would become personally acquainted with her, that we would treat her as gentlemen should treat a lady, and that we would in that manner put her under obligation to us—social obligation, kindly obligation.”

They talk of bringing their wives into the scheme—of having Mrs. Beecher, Mrs. Tilton and Mrs. Moulton befriend Victoria. Beecher declares that his wife—known among the Beechers as “the griffin”—will never cooperate. “Mr. Beecher said it was impossible for him to do anything in that regard with Mrs. Beecher; that she would never make any alliance with him to any such end; she was a hard woman to get along with, and she must be left out of that account.”

The plan proceeds without her. Tilton invites Victoria to his home, introduces her to Lib Tilton and generally acts ingratiatingly. Meanwhile he prints a series of articles flattering to Victoria and her cause in the Golden Age.

The plan appears to be working. Victoria responds to the overtures by asking Tilton to edit, for popular consumption, a version of her argument that women already possess the franchise by virtue of the original Constitution and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

Tilton accepts the assignment. “I took up the argument and, thinking thereby to do her a service, I spent a week in putting that argument in a close and compact shape, in as good English as I could command.”

A short time later Victoria has another request. “Mrs. Woodhull again sent for me and put into my hands a roll of manuscript, which she said was a biographical sketch of her life, written by her husband; that it was not written as satisfactorily to her as she desired it to be; and she asked me if I would take it and read it, and either revise it or amend it or make it out anew, that it might the more readily command the popular ear.”

Tilton again accepts the assignment. “I took that manuscript, and I read it, and I read it twice; and instead of merely revising it, I sat down, and at one heat, I wrote in what I designed to be a newspaper article the sum and substance of that narrative, a biographical sketch of Mrs. Woodhull. After it was done, I took it to her house in the evening. I read it to her. I had one it as well as I could.”

But Victoria doesn’t like it. “You have left out the most important parts,” she says.

“Well, I have left out some extravagant parts which I thought would mar the narrative,” he says.

“I wish you would put them in again.”

“What! Do you want me to say that you have called a dead child to life?”

“Yes, I do. For to write my life and leave out that incident would be to play the part of Hamlet with Hamlet omitted.”

“Do you want me to say, as this narrative has done by your husband, that you have had the power to heal the sick, like the apostles?”

“Yes, I do, because that is the exact truth.”

He asks if she wants him to restore the part about her receiving messages from the spirit world by way of Demosthenes.

“Yes, for he sometimes speaks through me.”

“Very well. If you want them all in I will put them in.”

Tilton retreats to the back parlor of Victoria’s house. For hours he writes of miracles and visits from the spirits. “I was there until two or three o’clock in the morning,” he says later. “When it was done I threw myself down on the sofa and slept all night, and took breakfast in the morning, and read it to the family. They pronounced it perfect. I went and published it.”