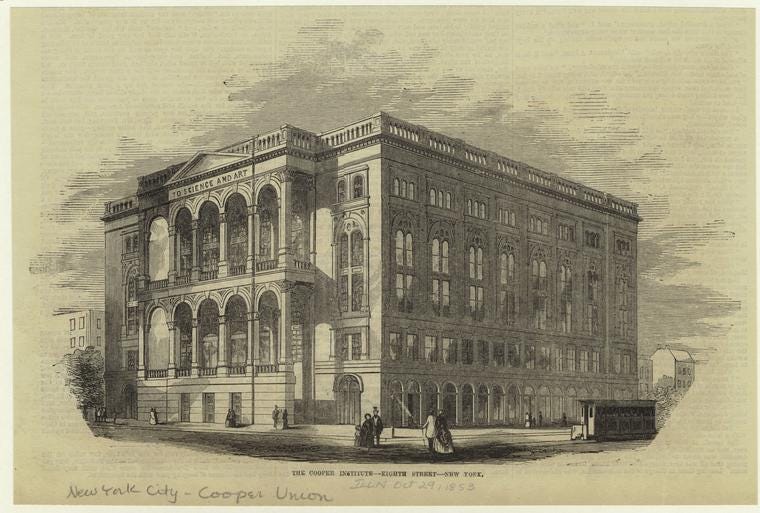

Victoria’s call for treason and secession thrills many most of those who have followed her remarkable rise and gets the attention of many who haven’t; it meanwhile puts her more in demand as a lecturer than ever. She hires the hall at New York’s Cooper Institute. “When the doors were opened a surging multitude was doing its best to get inside,” the Times explains, noting that the demand for tickets was enough to fill the hall twice. The address—substantively the same one she gave in Washington—evokes a delirious response. “She closed her lecture and walked off amid immense thunders of applause,” the World observes. “She was literally covered with bouquets as she made her exit.” A writer in the Herald praises Victoria to the heavens, literally. “If the women’s movement has a Joan of Arc, it is the gentle and yet fiery spirit, Victoria Woodhull,” the writer says. “She is one of the most remarkable women of her time.…She is a purest gem of the first water. Her sincerity, truthfulness, nobility and uprightness of character rank her as a pious Catholic would rank Theresa. She is a devotee, a religious enthusiast, a seer of visions.” The Tribune sticks to the secular in declaring Victoria the woman of the hour. “We toss our hats into the air for Woodhull,” the paper proclaims. “She has the courage of her own opinion. She means business. This is a spirit to respect. Would that the rest of those who burden themselves with the enfranchisement of one-half our population now lying in chains and slavery but had her sagacious courage.”

Victoria’s surging popularity causes the veteran suffragists to embrace her more tightly than ever. Elizabeth Stanton and Susan Anthony headline a meeting at New York’s Apollo Hall in May 1871; they insist that Victoria join them on the roster of speakers. Stanton kicks off the evening by borrowing the point Victoria has been making: that equality is indivisible. “There is but one safe and stable basis of national life: that is the equality of all the citizens,” Stanton says. “Equality must be the foundation of all true government.” But the political system has turned its back on equality. Stanton follows Victoria in blaming both parties. Reformers have expected much of the Republicans, the party that ended slavery, she says. But the Republicans have grown corrupt. “When Lincoln fell, the Republican regime gave us Andy Johnson, who convulsed the country for four years and only escaped impeachment by bribery, and now we have Grant, who is determined to make all men bow to him.…The Democratic party died with slavery; the Republican party has done its work, let it now be gathered to its fathers.”

Stanton yields the floor to Susan Anthony, who takes a cue from Victoria in declaring that women already possess the right to vote, if Congress will recognize the fact. “As women are counted in the basis of representation, subjected to taxation and punishment for crime, permitted to pre-empt lands, own property in American vessels, and take passports abroad, under the federal Constitution, they are citizens,” Anthony says. “And as under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments the specified right of all citizens to vote is plainly declared, we demand of Congress a law that shall secure to woman this fundamental right.” While reading her statement, Anthony is asked to speak up, as those in the back of the hall cannot hear. A gentleman volunteers his services as a reader. Anthony indignantly rejects the offer. “It is another piece of man’s presumption in imagining that he can read louder than a woman,” she says. “I beg to inform the gentleman that I can speak as loud as any man.”

Victoria doesn’t need to speak loudly when her turn comes; the hall falls utterly silent. She recapitulates her argument about women already possessing the vote, but she adds a twist. If Congress continues to fail women, she says, she will apply to the federal courts. Judges are bound by their oaths to follow the law, and, being appointed for life, they needn’t worry about reelection. She hopes the courts will see the light of wisdom. But if they don’t, women will have to take matters into their own hands. “If the country is ruled for the next twenty years as badly as it has in the last twenty years, liberty will be lost.…It is unwarrantable tyranny and despotism to deprive women of the franchise. We must have our rights. We will not give them up. If Congress refuses, we must adopt other means—to plant a government of righteousness instead of the government imposed upon us without our consent.”