4

Victoria’s visions, having carried her out of St. Louis and into the arms of James Blood, in 1868 propel her to New York and into the embrace of Cornelius Vanderbilt. Her supernatural guides have taken many forms, but one stands first. “The chief among her spiritual visitants, and one who has been a majestic guardian to her from the earliest years of her remembrance, she describes as a matured man of stately figure, clad in a Greek tunic, solemn and graceful in his aspect, strong in his influence, and altogether dominant over her life,” writes Theodore Tilton, to whom she has confided her gift. “For many years, notwithstanding an almost daily visit to her vision, he withheld his name, nor would her most importunate questionings induce him to utter it. But he always promised that in due time he would reveal his identity. Meanwhile he prophesied to her that she would rise to great distinction; that she would emerge from her poverty and live in a stately house; that she would win great wealth in a city which he pictured as crowded with ships; that she would publish and conduct a journal; and that finally, to crown her career, she would become the ruler of her people. At length, after patiently waiting on this spirit-guide for twenty years, one day in 1868, during a temporary sojourn in Pittsburgh, and while she was sitting at a marble table, he suddenly appeared to her, and wrote on the table in English letters the name ‘Demosthenes.’ At first the writing was indistinct, but grew to such a luster that the brightness filled the room. The apparition, familiar as it had been before, now affrighted her to trembling. The stately and commanding spirit told her to journey to New York, where she would find at No. 17 Great Jones Street a house in readiness for her, equipped in all things to her use and taste.”

Victoria feels she has no choice, and to New York she travels. And at 17 Great Jones Street she finds the residence her spirit described. “On entering the house, it fulfilled in reality the picture which she saw of it in her vision—the self-same hall, stairways, rooms, and furniture. Entering with some bewilderment into the library, she reached out her hand by chance, and without knowing what she did, took up a book which, on idly looking at its title, she saw (to her blood-chilling astonishment) to be ‘The Orations of Demosthenes.’”

This is Victoria’s story, and nothing can shake it. Demosthenes—or whoever—has chosen well, for the house on Great Jones Street has to be large to accommodate all the relatives who follow Victoria to New York. Her mother and father arrive, along with Tennessee. Three other sisters and various of their husbands and children fill the upstairs bedrooms. Victoria’s son and her younger child, a girl, occupy rooms of their own. Victoria’s two husbands complete the ménage.

The last pair are the ones that flummox the neighbors. Victoria still employs Canning Woodhull’s last name as her own, despite having claimed to divorced him. The divorce took place in Chicago, she says, although she doesn’t have the papers to prove it, and by the time anyone cares to check her claim, half of Chicago and many of its official records will have been destroyed in the great fire of 1871. Casting additional doubt on the divorce claim is Canning Woodhull’s presence in the house on Great Jones. But James Blood doesn’t seem to mind; he asserts that he is the lawful husband of the woman of the premises, and she corroborates his assertion despite employing his predecessor’s name.

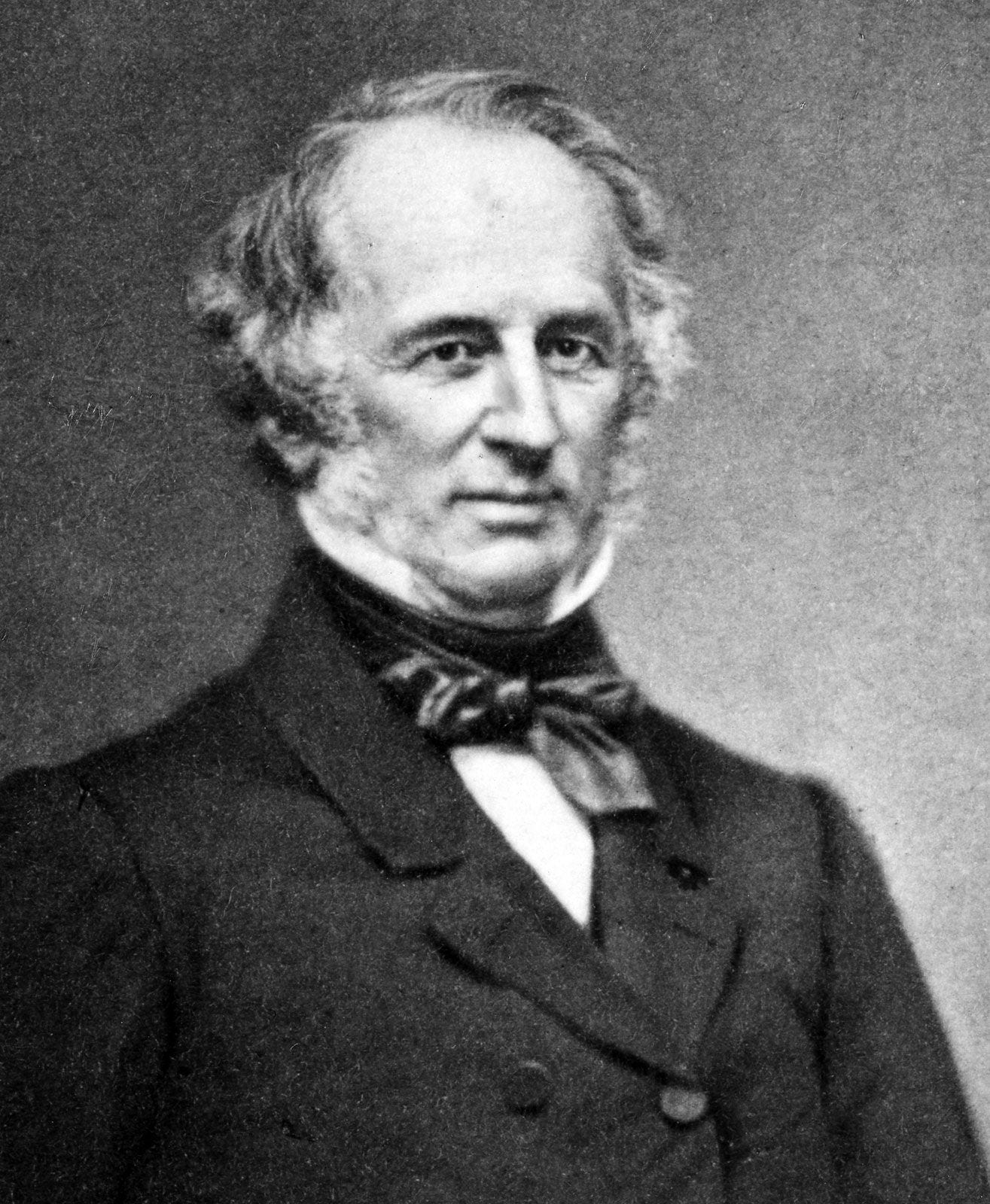

Supporting the tribe is an expensive undertaking, which is where Cornelius Vanderbilt comes in. The Commodore, as he has been called from his time in the steamboat trade, is the wealthiest man in America and, despite his seventy-three years, among the randiest. His wife of many decades has just died, and though the sad event has had little effect on his love life—he has long disported with younger women—it has changed the perceptions of his liaisons held by certain interested parties, namely his children and potential heirs. Should the Commodore remain single, they will inherit his hundreds of millions; should he remarry they will have to share the estate.

What Victoria has in mind for the Commodore she doesn’t say. Perhaps the name traced on the Pittsburgh table was actually “Vanderbilt” rather than “Demosthenes.” She can’t approach him directly, as she is a married woman. But her sister Tennessee can. Tennessee, named for the Volunteer state at a time when Buck Claflin hoped to practice some lucrative cons there, has begun writing her name as “Tennie C.” since coming east. She is unmarried, twenty-two and even more attractive than Victoria. She effortlessly plays the coquette, and after Victoria arranges a meeting for her with Vanderbilt, she is soon sitting in his lap, twisting her fingers in his flowing side-whiskers and teasing him with words and touch.

The Vanderbilt children take alarm. Their father has had many mistresses, but he seems unusually attached to his “little sparrow,” as he calls Tennie. He acts and speaks as though he might marry her. And the imagined sound of wedding bells hits the ears of William Vanderbilt and his siblings like the death knell of their dreams of fantastic wealth. They grumble against Tennie and Victoria, with the latter being, in their estimation, the malign intelligence behind the conspiracy to steal their inheritance.

5

Elizabeth Cady Stanton has been battling men her whole life. She has fought her father from the time she was a girl, her husband almost since their wedding, and male politicians from the time she realized important parts of the American constitution don’t apply to her. Her only brother died when she was eleven, prostrating their father, who was too dazed to notice her efforts to console him. “After standing a long while, I climbed upon his knee,” she remembers, “when he mechanically put his arm about me and, with my head resting against his beating heart, we both sat in silence, he thinking of the wreck of all his hopes in the loss of a dear son, and I wondering what could be said or done to fill the void in his breast. At length he heaved a deep sigh and said: ‘Oh, my daughter, I wish you were a boy!’”

For years she tries to be. She learns to ride horses, play chess, debate politics, speak and write Greek and Latin. She equals the best boys her age, winning, among other prizes, one for proficiency in the language of Plato. “How well I remember my joy in receiving that prize,” she recalls. “One thought alone filled my mind. ‘Now,’ said I, ‘my father will be satisfied with me.’” She takes the award home to her father. “Then, while I stood looking and waiting for him to say something which would show that he recognized the equality of the daughter with the son, he kissed me on the forehead and exclaimed, with a sigh, ‘Ah, you should have been a boy!’”

At twenty-four she marries Henry Stanton, an abolitionist ten years her senior. Her father doesn’t like Henry Stanton’s radical politics and discourages the match; perhaps this adds to Henry’s appeal. The wedding takes place on a whim: Henry is leaving for London to attend an international antislavery convention, and Elizabeth wants to join him. Propriety demands they travel as husband and wife. The ship is about to leave, necessitating a Friday wedding. The Presbyterian minister warns that a Friday wedding is bad luck, yet Elizabeth insists. She also insists that the traditional “obey” be dropped from the wedding vow. The reverend reluctantly grants this demand too. “But the good priest avenged himself for the points he conceded,” she recalls, “by keeping us on the rack with a long prayer and dissertation on the sacred institution.”

In London the couple attends the antislavery conference, although only Henry is admitted as a delegate. The English organizers, acceding to the clerics among them, refuse to seat the women representatives that various European and American groups have sent. “The clergymen seemed to have God and his angels especially in their care and keeping,” Elizabeth recalls wryly, “and were in agony lest the women should do or say anything to shock the heavenly hosts. Their all-sustaining conceit gave them abundant assurance that their movements must necessarily be all-pleasing to the celestials.”

Her experience in England opens her eyes to what she deems the hypocrisy of the clerics, and of the male abolitionists who sustain the clerics’ prejudice. The contradictions of the antislavery movement drive Elizabeth Stanton—and many of her sister abolitionists—to the campaign for women’s rights. She works to unfetter slaves only to discover the fetters that bind her; in advocating equality between the races she realizes how little equality her sex enjoys. Her view of reform broadens even as it grow more radical. Ending slavery will reshape the South, but ending the oppression of women will transform American society as a whole.

Her radicalization receives encouragement from a kindred spirit she meets in London. Lucretia Mott is a radical Quaker abolitionist and an enthusiast of most kinds of reform. For six weeks Elizabeth spends every waking moment with Lucretia. “Mrs. Mott was to me an entire new revelation of womanhood. I sought every opportunity to be at her side, and continually plied her with questions.” Elizabeth cannot get enough of the liberal dispensation. “I had never heard a woman talk what, as a Scotch Presbyterian, I had scarcely dared to think.”

The heady sense of possibility diminishes upon the birth of her first child, and shrinks further with several subsequent births. The physical demands of motherhood aren’t the problem. “On Tuesday night I walked nearly three miles, shopped, and made five calls,” she explains of the last stages of one pregnancy. “Then I came home, slept well all night, and on Wednesday morning at six I woke with a little pain which I well understood. I jumped up, bathed and dressed myself, hurried the breakfast, eating none myself, of course, got the house and all things in order.” She delivers the baby in less than an hour. “At ten o’clock the whole work was completed, the nurse and Amelia alone officiating. I had no doctor and Henry was in Syracuse.” She resumes her household business that day and continues the next. “When the baby was 24 hours old I got up, bathed and dressed, sponge bath and sitz bath, put on a wet bandage, ate my breakfast, walked on the piazza, and then, the day being beautiful, I took a ride of three miles on the plank road, then I came home, rested an hour or so and then read the newspapers and wrote a long letter to Mama.” Reflecting, she adds, “Am I not almost a savage? For what refined, delicate, genteel, civilized woman would get well in so indecently short a time?”

Stanton loves her children but not the care they require. “My duties were too numerous and varied, and none sufficiently exhilarating or intellectual to bring into play my higher faculties. I suffered with mental hunger, which, like an empty stomach, is very depressing. I had books, but no stimulating companionship.” Tending to the little ones pushes everything else aside. “Cleanliness, order, the love of the beautiful and artistic, all faded away in the struggle to accomplish what was absolutely necessary from hour to hour.”

Relief arrives only—and only partially—after her situation grows even worse. The abolitionists don’t suffer fools or half-hearts, and they often don’t suffer one another. Henry Stanton falls out with his antislavery brethren and removes the family to Seneca Falls, New York. City-bred Elizabeth isn’t prepared for small-town life, and her sense of isolation deepens. Lucretia Mott visits during the summer of 1848 and sympathizes as Elizabeth pours out her woes. They talk the matter over with other women in the area; together the group decides to do what reformers during that era do best: hold a meeting.

“Woman’s Rights Convention,” they advertise in a local paper. “A convention to discuss the social, civil and religious rights of woman will be held in the Wesleyan Chapel, at Seneca Falls, N.Y., on Wednesday and Thursday, the 19th and 20th of July.” Elizabeth Stanton, Lucretia Mott and the other organizers reasonably expect a fair attendance, knowing the neighborhood’s penchant for reform. Yet they wish to ensure that the core of their intended audience gets the message. “During the first day the meeting will be held exclusively for women,” they add.

The minister who agrees to open his chapel to the event either forgets his promise or changes his mind, for when Stanton arrives on Wednesday morning the building is locked. But one of her nephews climbs through a window and releases the door. By ones and twos the interested and curious come, till a hundred women fill the pews. None of the organizers has ever run a public meeting, and they aren’t sure where to start. Mott’s husband, James, volunteers to preside. The organizers have already been having second thoughts about their opening-day ban on men, some of whom have come twenty miles or more with their wives. To turn them away would be rude. The men are allowed to remain, and James Mott gavels the meeting to order.

The centerpiece of the proceedings is a “Declaration of Rights and Sentiments.” Stanton has written it quickly after gathering her thoughts for years and talking for days with the other organizers. Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence provides the model and the inspiration. “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” she says: “that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” In place of George III, Stanton substitutes generic man; in place of the oppressed American colonists, oppressed American women.

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her.…

He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise.

He has compelled her to submit to laws in the formation of which she had no voice.

He has withheld from her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men, both natives and foreigners.…

He has made her, if married, in the eyes of the law civilly dead.

He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.…

He has monopolized nearly all the profitable employments.…

He closes against her all the avenues to wealth and distinction.…

He has denied her the facilities for obtaining a thorough education.…

He has created a false public sentiment by giving to the world a different code of morals for men and women.…

He has endeavored, in every way that he could, to destroy her confidence in her own powers, to lessen her self-respect, and to make her willing to lead a dependent and abject life.

Stanton stops short of declaring independence for women, but what she does demand is plenty radical for its time and place. “We insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States.”

The meeting endorses the declaration, with sixty-eight women and thirty-two men affixing their signatures. The gathering also ratifies a series of resolutions, of which the most concrete and controversial is the ninth: “That it is the duty of the women of this country to secure themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise.” Henry Stanton has told Elizabeth he’ll leave town if she insists on sponsoring this resolution. Lucretia Mott advises her to delete it. Lucretia and others fear that such a forceful claim for political participation will undermine support for the broader platform. But Elizabeth answers that the franchise promises the only protection for whatever other rights women might claim. Besides, in an age of democracy simple equity dictates that women be allowed to vote. “To have drunkards, idiots, horse-racing rum-selling rowdies, ignorant foreigners and silly boys fully recognized, while we ourselves are thrust out from all the rights that belong to citizens is too grossly insulting,” she says. The convention approves the suffrage plank, barely.

6

Susan B. Anthony misses the Seneca Falls convention because she isn’t nearby, but also because Anthony is more concerned just then with temperance than with women’s rights. Anthony is the daughter of a Quaker who lapsed far enough to marry a Baptist but not so far as to leave the Meeting. He apologized to the Meeting, which satisfied them but annoyed his wife. She engaged in subtle acts of resistance against the expectations of Quaker orthodoxy; of her several children, Susan is the one who noticed.

Susan also notices how women experience opportunities for independence that haven’t existed a short time ago. Massachusetts is the birthplace of the American textile industry, and Susan’s father becomes an early textile capitalist. He builds a mill in the town of Adams, with twenty looms, and he hires that many young women to tend them. Whenever one of the women falls sick, Susan is pressed into service. She discovers that loom-tending isn’t more onerous than the chores she does around the house, and in some ways is less so. The mill hours are long but limited; once the mill closes for the day, the workers are free till the morrow, as Susan is not when assigned to housework and caring for her younger siblings. And the mill girls make money, which promises personal freedom. Most don’t pursue the promise; after a year or two at the loom they go home and marry. But the promise alone is tantalizing, and to none more than to Susan.

She attends a female seminary—a private girls’ school—and graduates to become a teacher in Canajoharie, New York. Her peers pair off with young men and wed, but Susan never does. She eventually evolves a philosophy of the single life for women. “I would not object to marriage if it were not that women throw away every plan and purpose of their own life to conform to the plans and purposes of the man’s life,” she writes later. Of her own case she says, “I’m sure no man could have made me any happier than I have been.” But at the time she simply seems hard to please.

Certain young men who appear to have prospects disqualify themselves by a taste for alcohol. “Oh rum, horrid rum!” she diarizes indignantly after a dance where the punch has been spiked. On another occasion her escort gets tipsy, and she swears off any but a total abstinence man. “I cannot think of going to a dance with one whose highest delight is to make a fool of himself.”

As her horror at whiskey mounts, her patience for pedagogy wanes. “I have had to manufacture the interest duty compels me to exhibit,” she writes after a trying day at school. She begins seeking another outlet for her physical and moral energy. Temperance seems as a good a cause as any. Her father favors temperance, as do many of her neighbors. The young men of her acquaintance obviously need the guidance temperance affords. And the temperance movement welcomes women—more readily than the abolition movement does. Abolition requires grappling with government, a realm off limits to women, but temperance might begin in the home, the woman’s domain. Susan Anthony enlists in the Daughters of Temperance and gives her first public speech, in 1849, on the “corrupting influence of the fashionable sippings of wine and brandy, those sure destroyers of mental and moral worth.”

Where abolition is the vehicle that brings Elizabeth Stanton to women’s rights, Susan Anthony rides temperance to the same destination. She doesn’t require long to realize that though drunkenness damages society as a whole, it injures women and children especially. When husbands and fathers drink away wages, the women and children go hungry; when the men become abusive, the wives and little ones feel the blows. The realization doesn’t diminish her animus toward alcohol, but it awakens an insight into the need for women to protect themselves and their children.

A reform-minded person in upstate New York in the mid-nineteenth century can’t avoid the antislavery movement, and after the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 prompts the expansion of the Underground Railroad, Anthony gets involved. She attends abolitionist meetings and shelters escaping slaves on the last leg of their journey to Canada.

Her abolitionist work introduces her to Elizabeth Stanton. “How well I remember the day!” Elizabeth Stanton writes. “George Thompson and William Lloyd Garrison having announced an antislavery meeting in Seneca Falls, Miss Anthony came to attend it. These gentlemen were my guests. Walking home after the adjournment, we met Mrs. Bloomer and Miss Anthony on the corner of the street, waiting to greet us. There she stood, with her good, earnest face and genial smile, dressed in gray delaine, hat and all the same color, relieved with pale blue ribbons, the perfection of neatness and sobriety. I liked her thoroughly.”

Susan Anthony reciprocates, afterward acknowledging the “intense attraction” toward Elizabeth she felt from the start. The two discover a complementary character in their gifts. “In writing we did better work together than either could alone,” Elizabeth explains. “While she is slow and analytical in composition, I am rapid and synthetic. I am the better writer, she the better critic. She supplied the facts and statistics, I the philosophy and rhetoric.” Anthony might not put things quite so, but she too recognizes the neat fit between their capabilities. Stanton is the senior partner in the early going, being five years older, longer in the reform movement and more widely recognized. Anthony is the more mobile, lacking husband and children. She visits the Stanton household periodically, then ventures forth into the world Stanton can reach only vicariously.

(To be continued)

I like it a lot. Keep it coming.

Interesting way to approach this period in our history. Will be looking to see the reactions from readers.