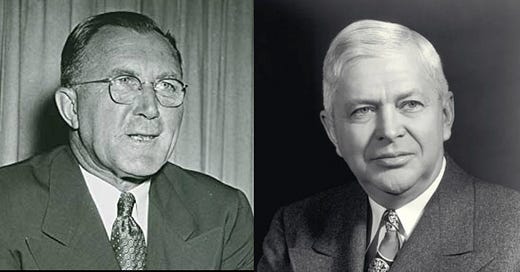

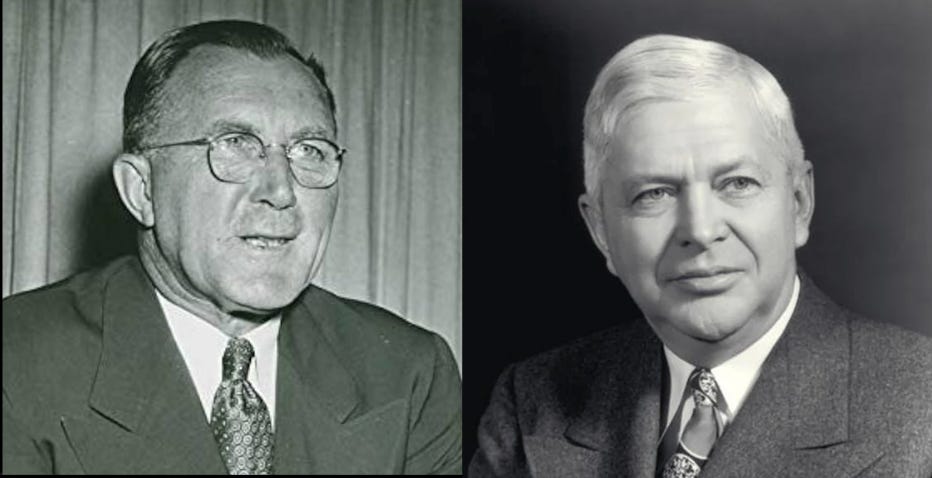

Charles Wilson was president of General Electric, one of America's largest and most powerful corporations, when he was asked to join the administration of Franklin Roosevelt. America had just entered World War II, and Wilson was appointed to the War Production Board, which effectively commandeered America's industrial economy for the duration of the war.

Wilson returned to General Electric at the end of the war but maintained his Washington connection. He chaired Harry Truman's Committee on Civil Rights, which recommended that the Pentagon end segregation in the armed services. In 1950, Truman made Wilson head of the Office of Defense Mobilization, overseeing the rapid buildup of the American military during and after the Korean War. Wilson was sometimes called America 's mobilization czar.

The title that rankled Truman more was “co-president.” Wilson's position prompted him to take a side when steelworkers demanded a pay increase to compensate for inflation. Wilson sided with management. Truman sided with the workers. Wilson resigned his position and returned to General Electric.

This wasn't the last America heard of Charles Wilson. But the Charles Wilson it subsequently heard of was a different Charles Wilson. This other Charles Wilson was also a business leader, president of General Motors. Confusion was inevitable. Adding middle initials was no help. The first Charles Wilson was Charles Edward Wilson. The second, who entered government service several months after the first departed, was Charles Erwin Wilson.

The second Charles Wilson ran the Pentagon under Dwight Eisenhower. To keep identities straight, he was called “Engine Charlie,” from his work building motors and the other parts of the cars General Motors produced. The first Charles Wilson retroactively became “Electric Charlie.”

The monikers eased the confusion only modestly. Many Americans conflated the two Charlies, who between them epitomized what Eisenhower would call the “military-industrial complex." Engine Charlie considered it a bad rap. He took seriously Eisenhower's order to streamline Pentagon operations and trim the American military budget. He responded to complaints that he might place the interest of General Motors before that of the United States by saying it had always been his belief that "what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa.” The commonly misquoted version put GM ahead of the US. Engine Charlie eventually stopped correcting it.

It's perhaps fitting that the modern incarnation of Electric Charlie and Engine Charlie is Elon Musk, who builds electric cars. Musk hasn't shown a conspicuous interest in history, but he might find the experiences of his predecessors illuminating. Each had the support of the president in bringing the disciplined thinking of business to the unruly arena of politics. The two Charlies had an arguably easier assignment, focusing on the military and not taking on the government as a whole, as Musk is doing.

Nonetheless each was frustrated and left government feeling defeated. They both discovered that Washington was a company town, not unlike Schenectady, the home of GE, and Detroit, of GM. The company was government, the business was politics, and the bottom line was getting reelected. In business the Charlies answered to boards of directors, with which they were in tune, since the boards had chosen them. In government they answered to the president, who had chosen them, but also to Congress, which had not. The members of Congress, moreover, answered to voters, who might have no sympathy whatsoever with the borrowed bosses.

Electric Charlie fell out with Truman over steelworkers’ wages. Wilson thought a pay hike would bake inflation into the economy and therefore must be resisted. Truman counted the workers as Democratic constituents.

Engine Charlie’s greater problem was with members of Congress whose districts included military bases and weapons factories. Over the years the defense budget had been designed to include as many such districts as possible. Every cut Wilson proposed met political resistance from the representatives of those districts, whose resistance was abetted by lobbyists for the defense industry and by uniformed officers who sabotaged anything that reduced their budgets and accompanying perks. During four years the resistance wore Wilson down. He resigned, with the budget bigger than ever.

The resistance wore Eisenhower down too. The president’s farewell warning about the military-industrial complex was aimed not at Wilson but at the lobbyists and the brass.

Elon Musk’s tour in government is only weeks old. Yet resistance to the cuts he has recommended is already forming. Sacked government employees are filing lawsuits. Voters in the districts where the ax will fall are berating their congressional representatives. Members of the House and a third of senators have November 3, 2026 circled on their calendars. The Republicans, who control Congress, will have to make a calculation between now and then whether they’re at greater risk from defying Donald Trump or defying their constituents.

Meanwhile Musk can take comfort from knowing what Electric Charlie and Engine Charlie understood: that if the political gig goes sour, there’s always the industry job to fall back on. They eventually bailed. He will too.

Don't forget businessman Robert McNamara as Secretary of Defense. One key aspect of his cost reductions was in aircraft where he considered there to be too much redundancy.

This attitude might work for automobile production but not necessarily for military aircraft. The redundancy mentality still existed in the Pentagon as it tried that with the F35 Joint Strike Fighter.

But each branch needed different performance and features for their aircraft which ended up making three different versions of the plane instead of a "joint" vehicle.

The attempt to create a universal combat aircraft for the Navy, Marines and Air Force caused cost over-runs so badly that the military tried to kill the program. But as you note in your article- Congress-people fought to keep the program because it was a JOBS program for their districts.

I was recently reading this great book: “the long hard road : lithium ion battery and the electric car.” and not surprisedly Musk’s name only appears in one chapter. He wasn’t a founder of Tesla but he did end up firing one of the founders. The other two founders eventually left the company.