There is no record that Adam and Eve ever formally married, either before or after they had Cain, Abel and Seth. Adam hinted at the institution of marriage when he said, "Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and shall cleave unto his wife, and they shall be one flesh." It's hard to know what to make of this statement, given that Adam did not have a mother or a father, and at this point he hadn't fathered any children.

Societies required time to introduce the institution of marriage. The practice of marriage apparently evolved as a way of controlling the sexual behavior of males and females and keeping track of children. In time, as some societies grew wealthier, marriage made the transmission of property from one generation to the next more predictable and regular.

Precisely when governments got in on the act is unclear. In ancient Greece and Rome rich folks made marriage contracts for their children. Poor folks didn't bother.

The Catholic church was slow to become involved and it did so to combat the teachings of heretical sects that treated procreation as evil. No, said the Council of Verona in 1184; marriage is a good thing. So good, in fact, that we're going to make it a sacrament.

Which was fine at times and in places where priests were available to perform marriages. But young love often couldn't wait, and informal marriages persisted.

England's King Henry VIII liked marriage so much he committed it six times. But he didn't like Catholic marriage law, which would have confined him to once. So Henry yanked England out of Rome's orbit, compelling the English to devise new marriage laws.

The ones they settled on remained in force when Benjamin Franklin and Deborah Read Rogers were contemplating wedlock in the late 1720s. Ben and Debby had first met when he arrived in Philadelphia after fleeing apprenticeship and his family in Boston. He was seventeen and she three years younger. He showed promise, being a talented and well-spoken young man. And he acquired prospects by cultivating the governor of Pennsylvania. By the time he did, he made an attractive partner to Debby, who now was of marriageable age. They planned to wed.

But first he had to go to London to purchase equipment to set himself up as a printer, employing the credit of the governor. In London he discovered that the governor had no credit, and he was left to fend for himself. He took work in a print shop and amused himself in the great imperial capital.

Its sights and sounds caused his memory of Debby to fade. He wrote but once, to say he wouldn't be returning soon. She began to wonder if he was ever coming back to America.

Rather than grow old waiting for him, she looked about for a substitute. John Rogers, a newcomer to Philadelphia, caught her eye. Rogers proposed and they were married.

All seemed well for a while. But then rumors arose that he had been married before. He fell into debt and skipped town. A report from the West Indies suggested he had died there. But no death certificate reached Philadelphia, and in its absence Debby remained his wife. Or not, if indeed he had been married before. Debby found herself in legal limbo, uncertain whether she was married or ever had been.

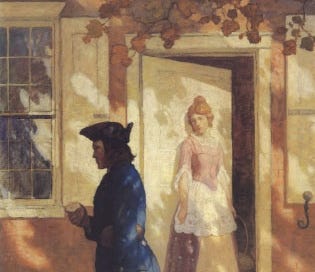

Ben eventually tired of London and returned to Philadelphia. He was embarrassed to encounter Debby, whom he had abandoned. She was embarrassed for having been abandoned by Rogers. Their mutual discomfiture eventually gave way to renewed affection and desire. They arranged to marry.

But they couldn't do so formally, given the clouds surrounding Debby's status. Informal marriage, as it had evolved under the traditions and practices of the English common law, offered an alternative. They would take up residence together and let the neighbors know they intended to live as husband and wife. In the event, however, that John Rogers reappeared, they would not have placed themselves in jeopardy of the laws against bigamy.

If he remained absent or dead, the common law marriage would acquire the same status as a formal marriage. Children born to the marriage would be spared the stigma of bastardy, and Debby would have the same claims on Ben's property that any wife had on her husband's.

Rogers never did reappear. The marriage of Ben and Debby lasted four and a half decades. He spent much of the last two decades in London representing the interests of the American colonies to the British government. She declined to join him, believing, no doubt correctly, that she wouldn't be comfortable in London society. The Franklin union wasn't quite such a model of marital bliss as that of John and Abigail Adams, for example, but its durability spoke well for the practical usefulness of common law marriage.

Brands, in his usual excellent article, writes "There is no record that Adam and Eve ever formally married." Although a Christian, I'm not a fundamentalist and don't believe the Adam, Eve, talking snake story in the Hebrew scriptures. Some fundamentalists call that the "domino theory of religion": Doubt the Adam and Eve story and pretty soon you'll doubt the Resurrection. Some theologians try to reconcile the truth of the scriptural creation story with evolution. But as the philosopher Bertrand Russell points out in one of his essays, that also presents problems. He asks humorously "at what stage of his development did Neanderthal Man become capable of eternal damnation?"