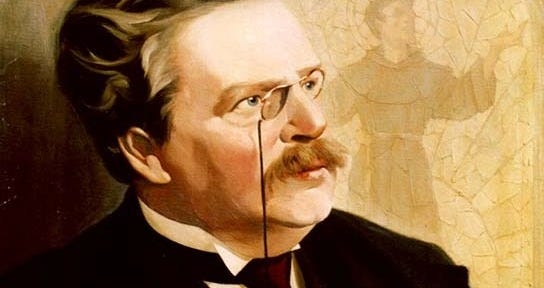

“In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle, a principle which will probably be called a paradox,” wrote G. K. Chesterton in 1929. “There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, ‘I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.’ To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: ‘If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.’”

Chesterton’s principle caught on. Called “Chesterton’s fence,” it declares that before making a change in some state of affairs, first discover why that state of affairs exists. Somebody had a reason for erecting that fence. Don't tear it down until you know what the reason was.

This is always good counsel, and not least when the president of the United States threatens to roll back history to the age of imperialism and seize the Panama Canal. When Theodore Roosevelt manhandled Colombia to spring Panama loose, in exchange for control of a strip of land on which to construct a canal across the isthmus, most of the world yawned. In the previous decades European imperialists had seized nearly the entire continent of Africa. The United States itself had annexed the Philippine archipelago, comprising seven thousand islands. A strip across Panama seemed hardly worth a fuss.

Times changed. Two world wars discredited imperialism, compelling the imperialists to relinquish the territory they had seized. The United States led the way by freeing the Philippines in 1946. Britain surrendered India and large parts of Africa and the Middle East. France followed, grudgingly in Southeast Asia after a nasty war in Vietnam, and even more grudgingly in North Africa after an even nastier war in Algeria.

It was in this context that the United States during the 1960s confronted nationalist violence in Panama, where it clung to the canal zone. The context also included the Castro revolution in Cuba and the Cuban missile crisis. Lyndon Johnson, while directing America's war in Vietnam, had no appetite for another war closer to home. He commenced negotiations with the government of Panama on the future of the canal zone.

The negotiations went very slowly. They outlasted Johnson. They outlasted Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. By the time Jimmy Carter became president, the United States had lost the Vietnam War and Americans were most reluctant to embark on anything like it. Moreover, Carter had his hands full with incipient revolutions in Iran and Nicaragua. As a final impetus to settlement, the last of the European imperialists in Africa, Portugal, had recently thrown in the towel in Angola. For the United States to appear more retrograde than Portugal was a very bad look for American democracy.

The Panama canal was a crucial lifeline for the American economy. But Carter's military and intelligence people told him it would be nearly indefensible against sabotage should Panamanian nationalists determine to do it harm. Panamanians were most of the workers on the canal. They came and went by the thousands every day. The canal would be safer in Panamanian hands.

Carter took the advice and concluded an agreement with Omar Torrijos, the leader of Panama. Embodied in two treaties, the agreement specified that Panama would regain control of the canal zone in 1999.

Republicans led by Ronald Reagan, former California governor and a likely challenger to Carter in 1980, criticized Carter and the treaties but failed to prevent their ratification by the Senate.

Other challenges emerged between Panama and the United States, leading to an American invasion of the country in 1989 and the seizure and extradition of Manuel Noriega, who spent seventeen years in American prison after being convicted of drug smuggling and money laundering. But through it all the canal operated smoothly. By 1999 the handover was a non-issue in American politics.

The canal remained a non-issue until Donald Trump raised it. Perhaps he's not serious in threatening to seize the canal. Possibly this is merely the opening gambit in negotiations to lower tolls on American shipping.

But if he is serious, he ought to think seriously about why the canal zone was returned to the Panamanians and what a reversal of the return agreement would signify to the world. It would immediately place the United States in the odious company of Russia in reneging on solemnly ratified treaties. Russia agreed to the independence of Ukraine and now is employing military force to bring Ukraine back under Russian control. If Trump follows through on his threat, the United States will be doing the same to Panama. America's moral case against a Chinese attempt to re-subjugate Taiwan will be gravely eroded.

Trump's action would revive Panamanian nationalism against the United States and would render the canal vulnerable to nationalist sabotage once more. Trump has complained about a pernicious Chinese influence in Panama, without providing evidence. His threats might cause the government to Panama to seek a foreign protector. China might be willing to oblige, at least diplomatically and economically.

Americans have become inured to Trump's bluster. His threats and subsequent reversals have become so common as to rarely register in America. Foreigners and their governments are not yet so nonchalant. Nor should they be. In countries like Panama, national sovereignty is at stake.

There's no reason to think Trump himself is familiar with how the current situation in Panama came to be. But his advisers ought to be, and they ought to let him know that things could get a lot worse. They were a lot worse before the Panama treaties took effect.

January has been a whirl of Presidential pardons and Executive Orders from both the outgoing and incoming administrations. I am pretty certain I know what the Constitution says about both (pardons explicitly stated in Article II, Section 2; Orders inferred by the “Take Care Clause” of Article II, Section 3), but I am deficient in my knowledge of their use by each of the 45 prior occupants of the White House. I would appreciate your thoughts on both in an upcoming essay.

I have reread Jefferson’s Inaugural Address to restore serenity to my present political soul and consoled by the knowledge of Jefferson and Adams’s reconciliation.

Two words that should never be used in the same sentence when referencing Trump: think seriously"- He doesn't- and he won't listen to advisors either