Caution: Midterms ahead

Midterm elections are always important. At the most basic level, they determine who will control Congress during the second half of a president's term. If the president's party gains or retains control of Congress, that president's final two years will be smoother and more productive than otherwise. Moreover, midterm elections serve as a reality check on a president. Especially in the days before public opinion polling, they indicated how voters were perceiving the performance of the president. Then and now, they could and can help a first-term president decide whether to run for a second term. They can cause would-be successors to the president to start campaigning, or to decide to sit on the sidelines for another four years.

No midterm election has had a greater effect on American history than the 1866 congressional races. Never has the landscape of American politics been more convoluted. The Democratic party had broken into three pieces in 1860 and it remained divided. A rift of suspicion separated Tammany Hall and its ilk in the East from the Midwesterners who had loved Stephen Douglas; a wider gulf yawned between those two constituencies and the rebel Southern Democrats. Republicans were barely more coherent, with Radical Republicans fighting conservatives over the legacy of Abraham Lincoln.

The Civil War had finished, but the map of American politics was still being contested. Lincoln and the Republicans had gone to war asserting that the eleven states of the Confederacy had never really left the Union; they were merely in rebellion. But now that Lincoln was dead, his heirs—especially the Radicals—were saying that those states were not part of the Union, at least not sufficiently to vote and send representatives and senators to Congress. Meanwhile, the Southern Democrats who had claimed during the war that they weren’t part of the Union now asserted unblushingly were, and should be treated as though the late unpleasantness had never happened.

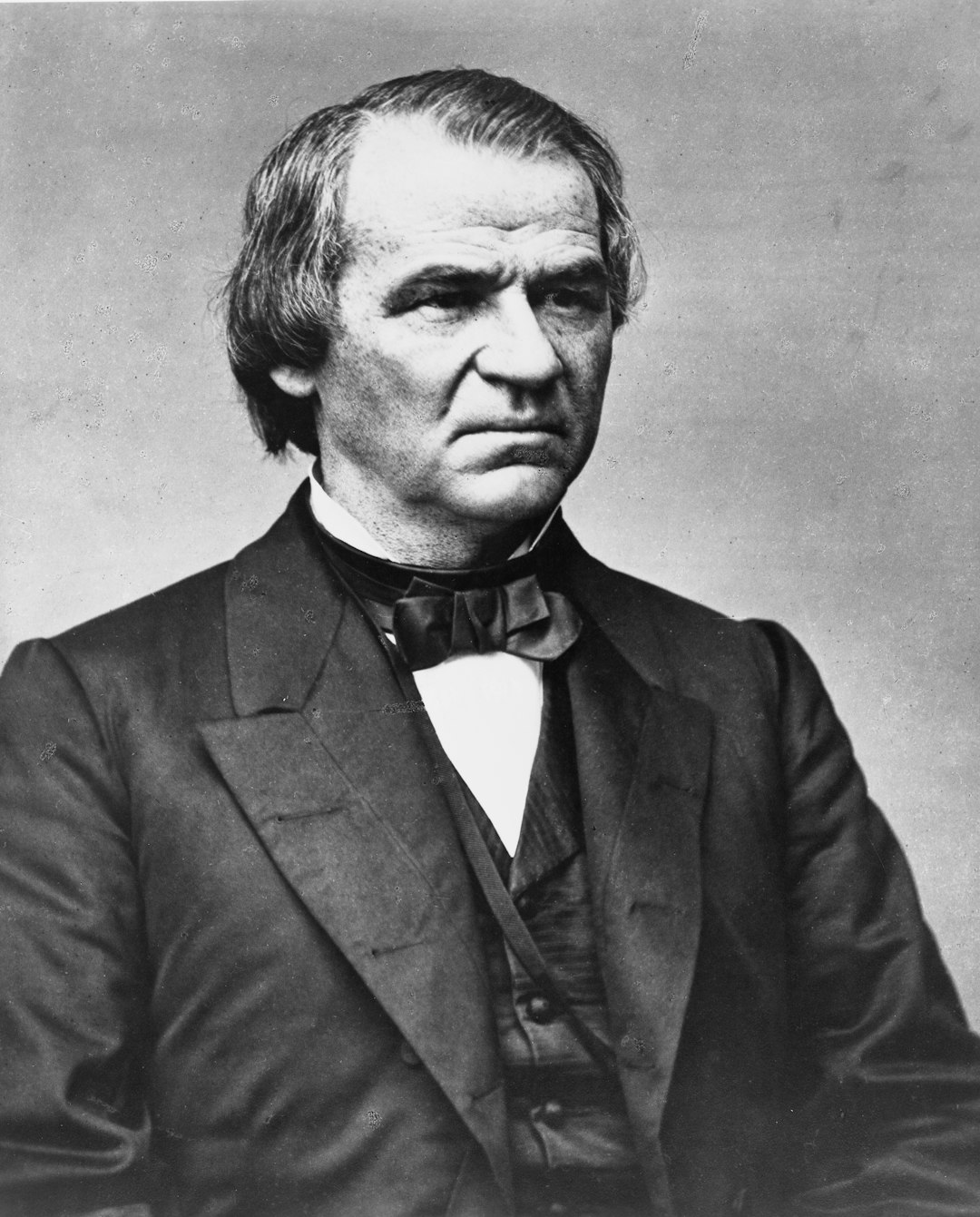

At the center of the multiple controversies, although not on the ballot, was Andrew Johnson. The Tennessee Unionist—a rebel against his own rebel state—had seemed to Lincoln a good fit for the president’s unity ticket in 1864, but no one had ever intended that Johnson be president. The Republicans of all stripes resented the presence of this Southern Democrat in the chair of Lincoln; none of them believed he should have the guiding role in Reconstruction.

Johnson himself had never expected to be president. He knew he been a ticket balancer for Lincoln. But upon Lincoln's death, Johnson had the epiphany common to all vice presidents who inherit the White House: that he was president of the United States. No matter how unlikely his path that position, he was now the man at the center of American politics. And he was reluctant to step aside.

Instead he stepped right into the middle of the muddle of the midterm elections. Until then, presidents had not campaigned for other candidates. Such politicking demeaned their own dignity and that of their office. Dignity was not a priority with Johnson. A tailor by trade, largely illiterate until adulthood, Johnson treated politics like a frontier brawl. He liked nothing better than trading insults and slanders with his rivals.

In the early autumn of 1866, Johnson made a "swing around the circle"— a counterclockwise loop north from Washington to New York, then west to the Ohio Valley and south and east back to Washington. One reason presidents hadn't done this sort of thing before was that railroads hadn’t existed to make it possible. What would have taken three months a generation earlier, Johnson accomplished in eighteen days.

He spoke vigorously and often on behalf of the magnanimous Reconstruction policy he had inherited from Lincoln, and on behalf of candidates who supported it. But Johnson wasn't Lincoln, and he had none of the aura of the Great Emancipator. Anyway, the Radical Republicans would have disputed Lincoln's policy had Lincoln lived. Disputing that policy when it bore Johnson’s name was irresistible.

The Radicals placed hecklers in the crowds that turned out to hear Johnson. They baited him off topic, and he took the bait, engaging in shouting matches that made him look less presidential than ever.

The heckling was tactical but also substantive. In recent months, riots in Memphis and New Orleans had turned into massacres of Republicans, some whites but mostly blacks. The Radicals asserted that the violence revealed the bankruptcy of Johnson's Reconstruction policy. They aimed to wrest control of Reconstruction from the president and take charge themselves. They would remand the Confederate states to military control, re-launching Reconstruction ab initio.

When the Republicans, led by the Radicals, prevailed in the midterm elections, that’s exactly what they did. As soon as the new Congress convened, the Radicals launched an all-out assault on Johnson. They passed a series of measures imposing military rule on the South, prescribing strict standards for lifting military rule, and making Congress the judge of whether the standards had been met. When Johnson vetoed the measures, they overrode his veto.

They also passed the Tenure of Office Act, which forbade the president to fire members of his cabinet. As they expected, Johnson challenged it by firing the secretary of war, Edwin Stanton. This gave the Radicals the excuse they needed to impeach Johnson.

He escaped conviction in the Senate by a single vote. But his presidency was dead in the water. The Radicals reigned supreme.

The lesson for future presidents should have been to eschew involvement in midterm elections. Presidents who get involved risk making the elections referendums on themselves—if the candidates they stump for lose. If the candidates win, those candidates claim the credit for themselves.

But it's been a hard lesson to heed. Franklin Roosevelt didn’t do so, and when the candidates he backed in 1938 lost, his plans for another round of New Deal reform were as dead in the water as Johnson's post-1866 presidency was.

Joe Biden has made a few campaign appearances for Democrats around the country ahead of this November’s midterms. He’d be smart to avoid many more. There’s not much upside, and a lot of down.

I appreciate the article. I have a question though. I think that it should be obvious that our republic is the best form of government seen in the history of the world, I think everyone could agree with that, but currently, our government is a bit messy. I also know that our government hasn't changed much since its founding as we have barely amended it over the nearly three hundred years it has existed. What do you think went wrong between our founding, and now, to make our government the mess it currently is?

Thanks for this. Great background history of this crucial period. I recently read Stahr's book on SALMON P. CHASE and I learned a lot about this ardent Unionist and his contributions to the Union, the war and Lincoln's cabinet.

You wrote:

"But it's been a hard lesson to heed. Franklin Roosevelt didn’t do so, and when the candidates he backed in 1938 lost, his plans for another round of New Deal reform were as dead in the water as Johnson's post-1866 presidency was."

I think you are right that Biden won't make many appearances. Mr. Biden is so unpopular all he can do is hurt his cause and his side. If the polls are correct BIden's presidency will essentially be checkmated for the rest of his term. Biden will become, very early, a lame duck.

Thanks again for an excellent and cogent article. I love your books and enjoy reading these articles. To me you are one of the top modern American historians.