Cast down your bucket where you are

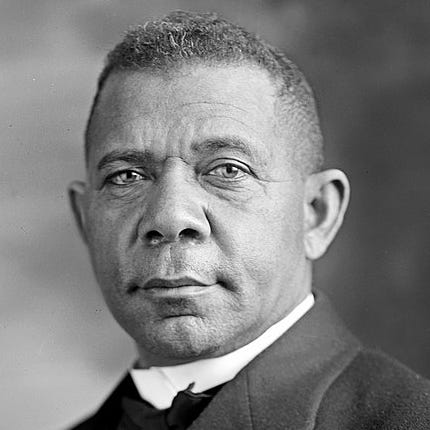

Booker Washington and the Atlanta Compromise

“When I first came to Tuskegee, I determined that I would make it my home,” Booker T. Washington recalled. Washington had been born into slavery in Virginia; emancipation arrived while he was a boy. He attended the Hampton Agricultural and Industrial School, founded by Northern missionaries in Reconstruction Virginia, and upon graduation was recommended for principal of the new Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers, in Tuskegee, Alabama. He received the job offer, accepted it and relocated to Tuskegee.

The creation of the Tuskegee school had been part of a political deal between blacks, who hadn’t yet lost the vote in this part of Alabama, and whites; and Washington respected the bargain. “I would take as much pride in the right actions of the people of the town as any white man could do,” he said of his new home. “I would, at the same time, deplore the wrong-doing of the people as much as any white man. I determined never to say anything in a public address in the North that I would not be willing to say in the South. I early learned that it is a hard matter to convert an individual by abusing him, and that this is more often accomplished by giving credit for all the praiseworthy actions performed than by calling attention alone to all the evil done.”

Washington didn’t deny the evil. “I have not failed, at the proper time and in the proper manner, to call attention, in no uncertain terms, to the wrongs which any part of the South has been guilty of,” he said. “I have found that there is a large element in the South that is quick to respond to straightforward, honest criticism of any wrong policy.” But, again, there was a time and place for everything. “As a rule, the place to criticize the South, when criticism is necessary, is in the South—not in Boston. A Boston man who came to Alabama to criticize Boston would not effect so much good, I think, as one who had his word of criticism to say in Boston.”

Southern leaders took note of Washington’s attitude and offered him a forum. He was invited to speak at the opening of the Cotton States Exposition in Atlanta in 1895. He accepted the invitation, fully aware of the responsibility it placed upon him. “I remembered that I had been a slave; that my early years had been spent in the lowest depths of poverty and ignorance, and that I had had little opportunity to prepare me for such a responsibility as this. It was only a few years before that time that any white man in the audience might have claimed me as his slave; and it was easily possible that some of my former owners might be present to hear me speak.

I knew, too, that this was the first time in the entire history of the Negro that a member of my race had been asked to speak from the same platform with white Southern men and women on any important national occasion. I was asked now to speak to an audience composed of the wealth and culture of the white South, the representatives of my former masters. I knew, too, that while the greater part of my audience would be composed of Southern people, yet there would be present a large number of Northern whites, as well as a great many men and women of my own race.”

As the day grew closer, the burden got heavier. “On the morning of September 17, together with Mrs. Washington and my three children, I started for Atlanta,” Washington recalled. “I felt a good deal as I suppose a man feels when he is on his way to the gallows. In passing through the town of Tuskegee I met a white farmer who lived some distance out in the country. In a jesting manner this man said: ‘Washington, you have spoken before the Northern white people, the Negroes in the South, and to us country white people in the South; but in Atlanta, tomorrow, you will have before you the Northern whites, the Southern whites, and the Negroes all together. I am afraid that you have got yourself into a tight place.’ This farmer diagnosed the situation correctly, but his frank words did not add anything to my comfort.”

The moment arrived, and Washington went straight to his point. “One third of the population of the South is of the Negro race,” he said. “No enterprise seeking the material, civil or moral welfare of this section can disregard this element of our population and reach the highest success.” For better or worse, the fates of the two races in the South were joined.

During the final decade of the nineteenth century, some black leaders preached emigration to Africa as a cure for their people’s problems. At the same time, white industrialists looked to Europe for the workers who would fill their factories. Washington had a message for both, by way of a story.

“A ship lost at sea for many days suddenly sighted a friendly vessel,” he said. “From the mast of the unfortunate vessel was seen a signal, ‘Water, water; we die of thirst!’ The answer from the friendly vessel at once came back, ‘Cast down your bucket where you are.’ A second time the signal, ‘Water, water; send us water!’ ran up from the distressed vessel, and was answered, ‘Cast down your bucket where you are.’ And a third and fourth signal for water was answered, ‘Cast down your bucket where you are.’ The captain of the distressed vessel, at last heeding the injunction, cast down his bucket, and it came up full of fresh, sparkling water from the mouth of the Amazon River.”

Washington drew the moral from his story. Looking at the black men and women crowded in the balcony of the hall, he said, “To those of my race who depend on bettering their condition in a foreign land, or who underestimate the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the Southern white man, who is their next-door neighbor, I would say: ‘Cast down your bucket where you are’— cast it down in making friends in every manly way of the people of all races by whom we are surrounded. Cast it down in agriculture, mechanics, in commerce, in domestic service, and in the professions.”

Washington then spoke to the white people in the hall’s main section. “To those of the white race who look to the incoming of those of foreign birth and strange tongue and habits for the prosperity of the South, were I permitted I would repeat what I say to my own race, ‘Cast down your bucket where you are.’ Cast it down among the eight millions of Negroes whose habits you know, whose fidelity and love you have tested in days when to have proved treacherous meant the ruin of your firesides. Cast down your bucket among these people who have, without strikes and labour wars, tilled your fields, cleared your forests, builded your railroads and cities, and brought forth treasures from the bowels of the earth, and helped make possible this magnificent representation of the progress of the South.” Washington was referring here to the black workers who had built the hall and other structures of the exposition.

“Casting down your bucket among my people,” Washington continued, “helping and encouraging them as you are doing on these grounds and to education of head, hand, and heart, you will find that they will buy your surplus land, make blossom the waste places in your fields, and run your factories. While doing this, you can be sure in the future, as in the past, that you and your families will be surrounded by the most patient, faithful, law-abiding, and unresentful people that the world has seen. As we have proved our loyalty to you in the past, in nursing your children, watching by the sick-bed of your mothers and fathers, and often following them with tear-dimmed eyes to their graves, so in the future, in our humble way, we shall stand by you with a devotion that no foreigner can approach, ready to lay down our lives, if need be, in defense of yours, interlacing our industrial, commercial, civil, and religious life with yours in a way that shall make the interests of both races one.”

Washington held up his right hand to illustrate the words he now spoke: “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”

Washington thought he might have been considered presumptuous by some of the whites in his audience. He tempered his boldness by an aside to the blacks. “Whatever other sins the South may be called to bear, when it comes to business, pure and simple, it is in the South that the Negro is given a man’s chance in the commercial world,” he said. “Our greatest danger is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labour, and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life; shall prosper in proportion as we learn to draw the line between the superficial and the substantial, the ornamental gewgaws of life and the useful. No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem. It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top.”

Here Washington was speaking as well to Northern blacks like W. E. B. Du Bois, who emphasized the intellectual and professional advancement of blacks, especially the most gifted, whom Du Bois called the “talented tenth.” Du Bois demanded full rights for black people, all at once.

Washington rejected this course as impractical and counterproductive. “The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing. No race that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized. It is important and right that all privileges of the law be ours, but it is vastly more important that we be prepared for the exercise of these privileges. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera-house.”

Washington’s prioritizing of economic opportunity over political and social equality came to be called the “Atlanta compromise.” Du Bois and other Northern black intellectuals rejected it as demeaning, but Washington judged that it was the only path forward for most black people in the South.

As for Southern whites, they would never make a better bargain, Washington said. “I pledge that in your effort to work out the great and intricate problem which God has laid at the doors of the South, you shall have at all times the patient, sympathetic help of my race.” he promised. Both races would be the winners. “Beyond material benefits will be that higher good that, let us pray God, will come in a blotting out of sectional differences and racial animosities and suspicions, in a determination to administer absolute justice, in a willing obedience among all classes to the mandates of law. This, coupled with our material prosperity, will bring into our beloved South a new heaven and a new earth.”

Washington didn’t get all he wanted. But he got more than nothing. His offer lost some of its salience when the Supreme Court the next year gave its seal of approval to segregation in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson. Southern whites didn’t have to give Washington anything in return for his not pressing for social and political equality. Yet the bargain he outlined had its attractions still. Booker Washington became the favorite black man of white philanthropists, who gladly supported his conservative approach to race relations as an alternative to the more radical demands of Du Bois and the Northern intellectuals.

Du Bois and the others continued to scorn Washington’s compromise. But while they won occasional and mostly symbolic victories for the talented tenth, he helped the humble nine-tenths make modestly better lives for themselves, furrow by furrow, bucket by bucket.

In reading the complete text of the Atlanta address, one can appreciate the careful wording of Washington's work. He was addressing a difficult issue in a. dangerous time. Historians generally have sided with Dubois over the need for greater social equality among the races, but this would take another sixty years for this equality to become a reality. Thanks for providing the extended address.

I have studied Booker T. Washington and Dubois. Both had a case but it all depends on where you are in your life and who you are. I think Dubois is a rather tragic figure. Let us not forget he left the USA to live in Africa and became a Communist by the end of life. By many measures, Booker T. Washington was a happier and more successul figure in America as an American. Washington adapted to the world in which he lived; I think he accepted the fact that progress in racial relations would take generations. But in the mean time, Washington thought, African Americans have to take personal responsiblity for their education and training and their habits and be economically stable and successful. With economic success other opportunties would come.

My father worked in a slaughter house at night when he was in high school. To do so he had to sacrifice any social life or any sports (even though he had been a soccer star in his native land). This experience had a strong influence on his entire life. He learned to be almost completely self-sufficient and I would say socially isolated.

For example, he chose to have no friendships or social relationships with the workers at the slaughter house with the exception of some older workers who befriended him and looked after him while he slept returning home on the Manhattan to Brooklyn subway at 3AM. He was lucky in that his mother and sister fed him, shopped for any sundries he needed and washed and ironed his clothes. My father turned over HIS ENTIRE paycheck to his mother. She would give him $1.50 so he could see movies and have a small snack.

My father's chief relaxations were reading, Saturday movies and Sunday baseball games with his father. He usually went alone to the movies. I don't remember him ever saying he went to baseball games with his friends or alone. He had a few American acquaintences but really he had no intimate friends. This was big change from his early life when he was a popular athlete and had many many close friends. Sadly, he was separated by emigration from most of his close friends and many were killed in WW2. My father's early life from age 12 was focused almost completely on working to support his family as his father had lost his job in 1932 and did not go back to work until 1937. My father continued his industriousness after high school and studied at Brooklyn College where he graduated in 1937. Soon the war came and but my father continued in his pattern of perseverence. He began miltary service as a E-1 private and worked his way up to corporal and finally an NCO in the MPs. From there he went to OCS and became a 2nd Lt. He went overseas in 1943-46 and rose in rank to 1st Lt. After the war he went to NYU on the GI bill and had a career in business in which he was reasonably successful in achievement a stable career. I think he could have advanced economically much more if he had sacrificed his family life and intellectual life. But he chose to focus on his private family life and his private intellectual life. Others would bar hop or play golf on business trips. My father would read Homer in the original Greek in his hotel rooms in Atlanta. His chief hobbies were opera (listening and collected historial recordings), literature, languages, classic movies, plays and baseball. I think my father was somewhat lonely except for the close friendship with my mother and her friends. In someways he lived the solitary isolated life of a prisoner but he was never bored and I think he was happiest when he escaped into his music and books. We are shaped by our environment and its challenges but we also are shaped by individual choices in how we respond to those challenges. I never once saw my father inebriated. He drank beer and wine but not spirits. He believed in moderation. He smoked cigarettes for about 25 years but quit in his 40s and smoked only cigars. He loved smoking cigars. But on the advice of his doctor he quit cigars also in his 50s. He lived a reasonably long life and a very healthy one until he was 87 when he fell and broke his hip. Thereafter he declined physically but remained mentally sharp until the very end. His very last words were "I think this is the best breakfast I have ever had." He suffered a stroke and lingered a few days in the hospital. He was listening to Wotan's farewell (Lieb wohl) in the hospital. I was not present but my sister said he reacted and there were tears falling from his eyes. My father's last lesson to me is that there is such a thing a a Good Death. If one can say goodbye to one's loved ones and die without pain and suffering in bed surrounded by loved ones and beautiful music then one can say one has experieced a Good Death.