Herman Melville went to sea as a young man. He shipped out from New Bedford aboard the whaler Acushnet and plied the hunting grounds of the South Pacific. He jumped ship in the Marquesas Islands, where he gathered material for his first book. He observed what contact with the outside world was doing to the people and culture of Polynesia, and it made him wonder who were the savages and who the civilized. He described a campaign by French marines against the Typees, who had resisted the French invasion. The natives fought the strangers to a standstill, compelling the latter to retreat to their ship.

“The invaders, on their march back to the sea, consoled themselves for their repulse by setting fire to every house and temple in their route; and a long line of smoking ruins defaced the once-smiling bosom of the valley, and proclaimed to its pagan inhabitants the spirit that reigned in the breasts of Christian soldiers. Who can wonder at the deadly hatred of the Typees to all foreigners after such unprovoked atrocities?

“Thus it is that they whom we denominate ‘savages’ are made to deserve the title. When the inhabitants of some sequestered island first descry the ‘big canoe’ of the European rolling through the blue waters towards their shores, they rush down to the beach in crowds, and with open arms stand ready to embrace the strangers. Fatal embrace! They fold to their bosom the vipers whose sting is destined to poison all their joys; and the instinctive feeling of love within their breast is soon converted into the bitterest hate.”

The spoiling of Eden formed a central motif of Melville's Typee, and it captured the imagination of readers in America and England. Appearing in the 1840s, at a time when American soldiers and settlers were doing to the aboriginal peoples of North America what the French naval officers and missionaries were doing to the Polynesians, Typee found an audience among the many Americans unbeguiled by the propaganda of Manifest Destiny. Just as a split between North and South marked American attitudes towards slavery, so a division between East and West characterized thinking about Indians. Easterners, having long since seized all the Indian land there was to seize, had the luxury of criticizing Westerners whose hands were still dirty and bloody.

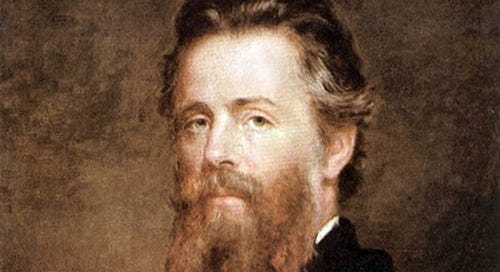

Melville was of the East. Born and raised in New York, he became a protege of Nathaniel Hawthorne, the bard of New England Puritanism. A strong Puritan streak would run through Melville’s greatest novel, Moby Dick, with its Bible-spouting and biblically named anti-hero Ahab.

Yet Typee was more to Americans’ taste than Moby Dick, as long as Melville lived. In its descriptions of nubile Polynesian girls clad in next to nothing, the book titillated even as it educated, in the genteelly erotic fashion that would make National Geographic magazine an item of intense interest to generations of teenage boys. Reviewers remarked on Melville's broad-mindedness in not condemning the islanders for moral laxity.

Melville wasn’t so naive as to think Polynesia entirely troubled. Yet on balance it measured well against the society from which he had come. “In a primitive state of society, the enjoyments of life, though few and simple, are spread over a great extent, and are unalloyed; but Civilization, for every advantage she imparts, holds a hundred evils in reserve—the heart-burnings, the jealousies, the social rivalries, the family dissentions, and the thousand self-inflicted discomforts of refined life, which make up in units the swelling aggregate of human misery, are unknown among these unsophisticated people.”

There was a particular aspect of Typee life that had to be explained to skeptical outsiders. “It will be urged that these shocking unprincipled wretches are cannibals. Very true; and a rather bad trait in their character it must be allowed. But they are such only when they seek to gratify the passion of revenge upon their enemies; and I ask whether the mere eating of human flesh so very far exceeds in barbarity that custom which only a few years since was practised in enlightened England—a convicted traitor, perhaps a man found guilty of honesty, patriotism, and suchlike heinous crimes, had his head lopped off with a huge axe, his bowels dragged out and thrown into a fire; while his body, carved into four quarters, was with his head exposed upon pikes, and permitted to rot and fester among the public haunts of men!”

Melville’s own sojourn in the Marquesas Islands was limited, and so is that of his alter ego. His hosts treat him well, but he worries that they might not always do so. When he discovers the preserved head of a white man, he decides not to risk winding up on the menu. With the aid of a ship’s captain short of sailors, he contrives his escape from Eden.

Typee made a name and a bit of money for Melville. Neither lasted long. And when his magnum opus, Moby Dick, hit bookshops in 1851 it landed with a thud. His final decades were spent in obscurity.

It took another few decades and the efforts of academics like Carl Van Doren for Melville’s reputation to revive. Moby Dick appeared on reading lists in college courses, where it remained for a half-century or so. Melville is still mentioned today but not read much more than in the last years of his life.

quote: Appearing in the 1840s, at a time when American soldiers and settlers were doing to the aboriginal peoples of North America what the French naval officers and missionaries were doing to the Polynesians,

and the english to the aboriginal people in Australia

I have read Moby Dick twice in the last 10 years. It is magnificent.