Canadian echoes of Calhoun

Nullification in Alberta

The provincial legislature of Alberta recently approved a measure called the “Alberta Sovereignty Within a United Canada Act.” The measure “defends Alberta’s interests by giving our province a legal framework to push back on federal laws or policies that negatively impact the province,” according to the bill’s sponsors. “The act will be used to address federal legislation and policies that are unconstitutional, violate Albertans’ charter rights or that affect or interfere with our provincial constitutional rights.”

This studied vagueness, and legal verbiage within the act itself, mask the radical—perhaps revolutionary—heart of the measure, which is that decisions on constitutionality will rest with the provincial assembly, and not with the supreme court of Canada. The act states that if, “in the opinion of the Legislative Assembly, a federal initiative (i) is unconstitutional on the basis that it (A) intrudes into an area of provincial legislative jurisdiction under the Constitution of Canada, or (B) violates the rights and freedoms of one or more Albertans under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms; or (ii) causes or is anticipated to cause harm to Albertans,” then the Lieutenant Governor in Council can “suspend or modify the application or operation” of the offensive federal measures or actions.

The history of Canada diverged from the history of what would become the United States when the United States diverged from the British empire in the 1770s and Canada declined to join the American secession. Canada never fully separated from Britain; indeed, the new act was approved during what its heading characterizes as “Fourth Session, 30th Legislature, 1 Charles III”—that is, in the first year of the reign of King Charles III. Moreover, the measure didn’t take effect until it received “royal assent”—a pro forma but still symbolic okay. Canada is not a republic but a constitutional monarchy, under the British crown.

Yet despite the differences between Canada and the United States, the two countries share certain challenges, including the question of where the line lies between national and local authority, and who will determine and defend that line. Like American states, Canadian provinces customarily and constitutionally handle certain issues of politics and law, while leaving others to the national government.

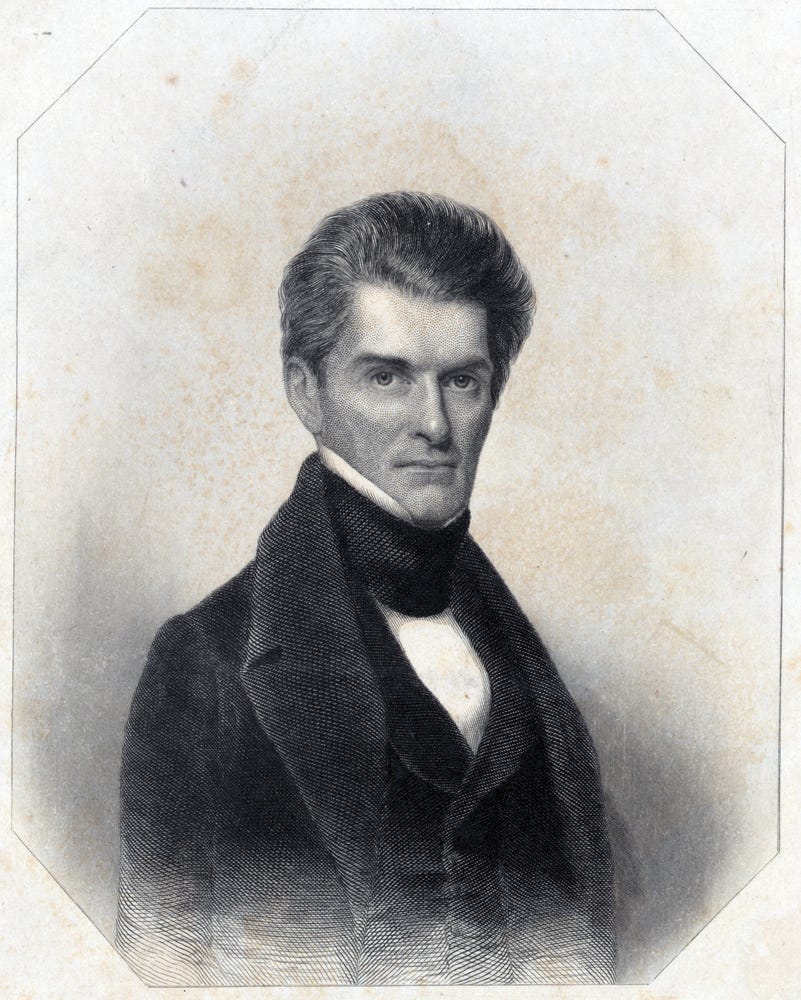

The new Alberta act has an American analogue: South Carolina’s 1832 Ordinance of Nullification, against a federal tariff of 1828. Authored by John Calhoun, the South Carolina ordinance singled out the tariff law—the “tariff of abominations,” its critics called it—as unconstitutional and henceforth annulled within the boundaries of the state. But the principle the ordinance rested on—that states could judge for themselves when the federal government had overstepped—had broad applicability.

The 1832 ordinance nearly led to war between South Carolina and the United States. Andrew Jackson angrily rejected the law and its premise, and he prepared to lead an army into South Carolina to enforce the tariff law and explode the pretensions of the nullifiers. Matters didn’t come to that: Henry Clay brokered a compromise that modified the tariff and rescinded the nullification ordinance.

Yet the question of where federal authority stops and state authority starts persisted, and it still does. The Civil War made clear that states can’t leave the Union, but short of that, we still argue about who—the states or the feds—should make voting laws, regulate abortion, fund education and health care, mandate vaccination, deal with immigrants and treat many other matters. We eventually agreed that our Supreme Court is the final arbiter on such issues, but the court itself changes its mind about which issues it will arbitrate.

Alberta, like several western states in the United States, has long chafed at federal restrictions on the use of land and other natural resources; again like some western states, it resents being made to follow rules written in a national capital far away, by people who don’t understand life in the West.

How far the fight over sovereignty will go in Canada remains to be seen. The national government has declined to rise to Alberta’s bait so far. It’s not clear what would trigger a confrontation, nor whether Albertans really want to go there. It may be that posturing will suffice for those behind the new act.

But you never know. South Carolina lowered its fists after the 1832 nullification crisis, but it never took off the gloves. When next crisis came, in 1860, it came out swinging. Alberta’s nullifiers, having made a big deal of provincial sovereignty, will be inclined to defend what they’ve asserted. At some point, on some issue, Canada’s national government will feel obliged to defend national sovereignty.

This story is far from over. It might be just beginning.

More years back than I care to count (think fall 1960) when I was taking my required Government class at UT Austin, a student asked the prof: "What is the definition of a legal revolution?" Without giving it a second's thought, the prof answered: "One that succeeds!" I think the same can be said of secession. A legal secession is one that succeeds. Back when the USSR and Yugoslavia were imploding, a columnist for _Time_ wrote (I'm paraphrasing): "The principle of secession in our own country wasn't decided by academics at a conference of historians and political scientists, but rather on the battlefields of Gettysburg and Antietam."

It should also be noted that most of the leaders of the so-called Freedom Convoy which converged on the Canadian capital in early 2022 are all from western provinces (Alberta, Manitoba, etc). Their views parallel rightwing views in the USA not just about the nature of federalism, but are also imbued with anti-semitic views (invoking Soros- as usual), Covid conspiracy rhetoric, and even invoking election conspiracy views about Dominion voting machines. It's exhausting!