Bring back the bosses!

Or at least their practical spirit

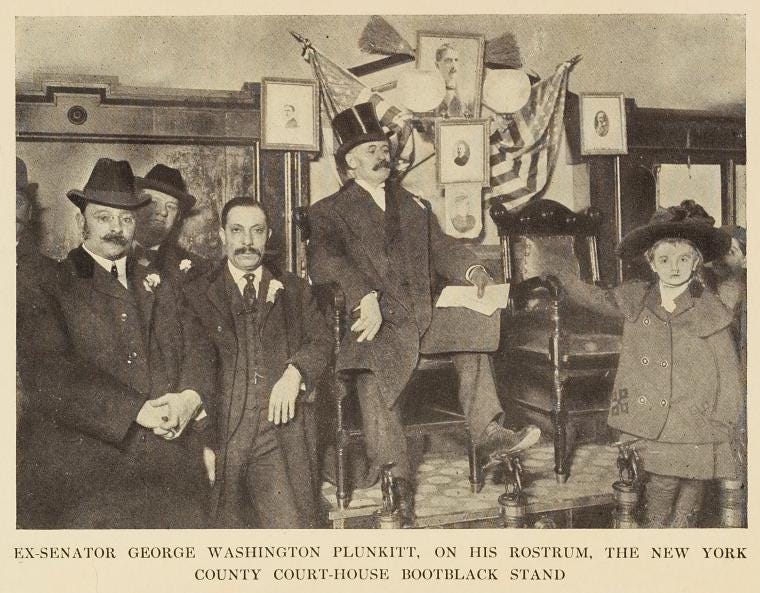

“Everybody is talkin’ these days about Tammany men growin’ rich on graft, but nobody thinks of drawin’ the distinction between honest graft and dishonest graft,” said George Washington Plunkitt to journalist William Riordon in the first decade of the twentieth century. Plunkitt was a New York state senator and Democratic stalwart, a member of the party organization known as Tammany Hall. “Yes, many of our men have grown rich in politics. I have myself. I’ve made a big fortune out of the game, and I’m gettin’ richer every day, but I’ve not gone in for dishonest graft—blackmailin’ gamblers, saloon-keepers, disorderly people, etc.—and neither has any of the men who have made big fortunes in politics. There’s an honest graft, and I’m an example of how it works. I might sum up the whole thing by sayin’: I seen my opportunities and I took ’em.”

Plunkitt gave an example. “My party’s in power in the city, and it’s goin’ to undertake a lot of public improvements. Well, I’m tipped off, say, that they’re going to lay out a new park at a certain place. I see my opportunity and I take it. I go to that place and I buy up all the land I can in the neighborhood. Then the board of this or that makes its plan public, and there is a rush to get my land, which nobody cared particular for before. Ain’t it perfectly honest to charge a good price and make a profit on my investment and foresight? Of course, it is. Well, that’s honest graft.”

Plunkitt observed that trading on informed insight was nothing more than what Wall Streeters did every day. The money men profited far beyond what a public servant could make, and they were lionized, not criticized. Was that fair?

Moreover, Tammany provided public services. “I’ve got a regular system for this. If there’s a fire in Ninth, Tenth, or Eleventh Avenue, for example, any hour of the day or night, I’m usually there with some of my election district captains as soon as the fire-engines. If a family is burned out, I don’t ask whether they are Republicans or Democrats, and I don’t refer them to the Charity Organization Society, which would investigate their case in a month or two and decide they were worthy of help about the time they are dead from starvation. I just get quarters for them, buy clothes for them if their clothes were burned up, and fix them up till they get things runnin’ again. It’s philanthropy, but it’s politics, too—mighty good politics. Who can tell how many votes one of these fires brings me? The poor are the most grateful people in the world, and, let me tell you, they have more friends in their neighborhoods than the rich have in theirs.”

Tammany took care of its constituents, and they took care of Tammany. “I know every man, woman, and child in the Fifteenth District, except them that’s been born this summer and I know some of them, too. I know what they like and what they don't like, what they are strong at and what they are weak in, and I reach them by approachin’ at the right side. For instance, here's how I gather in the young men. I hear of a young feller that’s proud of his voice, thinks that he can sing fine. I ask him to come around to Washington Hall and join our Glee Club. He comes and sings, and he’s a follower of Plunkitt for life. Another young feller gains a reputation as a base-ball player in a vacant lot. I bring him into our base-ball club. That fixes him. You’ll find him workin’ for my ticket at the polls next election day. Then there's the feller that likes rowin’ on the river, the young feller that makes a name as a waltzer on his block, the young feller that's handy with his dukes. I rope them all in by givin’ them opportunities to show themselves off. I don’t trouble them with political arguments. I just study human nature and act accordin’.”

Plunkitt’s view of the beneficence of Tammany Hall wasn’t universally shared. Reformers regularly decried the graft Tammany skimmed from contracts and services, and they pointed out that that money came out of taxpayers’ pockets. Occasionally a graft more egregious than usual provoked sufficient uproar that Tammany got tossed out of power for a time. But Plunkitt’s formula—of providing needed services in exchange for grateful votes—persisted for decades. The power of Tammany Hall, and Tammany’s counterparts in other cities in America, was broken only when government formally began providing the services Tammany had been providing informally. In some cities the transition took place during the Progressive era of the early twentieth century; elsewhere it awaited the New Deal in the 1930s.

Which model was more humane and efficient is hard to say. The government version required an increase in taxes, but the graft of the Tammany era was, in essence, a tax. The government model was theoretically more transparent, but the bureaucracies that grew up to provide the services could be as opaque in their own way as Plunkitt’s “honest graft.”

One thing Plunkitt’s approach had that modern politics could benefit from was a clear-eyed practicality. For Plunkitt, politics was about solving problems—the day-to-day problems of ordinary people. If Plunkitt had been asked what his philosophy or ideology was, whether he was a liberal or a conservative, he would have laughed at the inanity of the question. Indeed he loved to roast “the college professors and philosophers,” as he called them, who pontificated on politics but knew nothing of people. When William Riordon gathered Plunkitt’s comments into a small book, it bore the subtitle “A Series of Very Plain Talks on Very Practical Politics.”

One of the reasons politics today is so nasty and bitter is that it is performative rather than practical. Politics has become part of people's identity, in a way religion used to be. Politicians pose and make statements, and are judged accordingly, rather than on what they get done; unsurprisingly, less and less gets done. We could do without some of Plunkitt’s “honest graft,” but our public affairs would benefit from a large dose of his conviction that politics is the practical art of bettering lives.

Professor Brands, I just used two of these quotes with my APUSH class last week when talking about the rise of Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed during and after the Civil War. Glad to have a picture of Mr. Plunkitt-he has less hair than I imagined. I said a similar thing that you did-we may hate the corruption of those machines, but they DID get things done and provided an avenue for the integration of all the immigrants flowing into the cities during the late 1800s. Practical politics indeed. (And I type this as my school system in Delaware is closed because of 3-4 inches of snow, snow that could be reasonably easily removed if the government was more practical and less "performative." But I'm teaching on-line because yeah, that works well.)