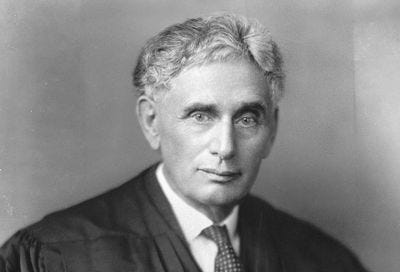

Louis Brandeis had grown up with the giant trusts and never liked them. Born in 1856 in Louisville to Jewish immigrants from Bohemia, he watched from one or two states over as John Rockefeller built Standard Oil in Ohio and Andrew Carnegie assembled Carnegie Steel in Pennsylvania. Brandeis’s parents expected great things from him, and he did not disappoint; heading east in his middle teens for education, he graduated from Harvard Law School at the age of twenty with the highest grade point average in the school’s history.

He opened a law practice in Boston and took as clients various businesses and their owners. But their causes never engaged his sympathies as much as those of their workers and customers did. The emergence of the progressive movement in the 1890s found Brandeis at its intellectual cutting edge. Labor relations became a specialty.

In 1912, when progressives in Congress launched an investigation into the conduct of the United States Steel Corporation, the successor to Carnegie Steel, they called Brandeis to testify. He criticized various practices of the steel trust but focused particularly on the power the corporation wielded over its workers. Steel workers often labored 12 hours a day for 7 days a week; the work was so rigorous that many were old men by the age of 40. Labor unions had made inroads at other companies and in other industries, but U.S. Steel had stoutly resisted them.

Brandeis pointed out the irony in this. “While the corporation is the greatest example of combination, the most conspicuous instance of combination of capital in the world, it has, as an incident of the power which it acquires through that combination and through its association with railroads and the financial world, undertaken—and undertaken successfully—to deny the right of combination to the working man,” he said. “And these horrible conditions of labor, which are a disgrace to America, considering the wealth which has surrounded and flown out of this industry, are the result of having killed, or eliminated from the steel industry, unionism. All the power of capital and all the ability and intelligence of the men who wield and who serve the capital have been used to make practically slaves of these operatives.”

As onerous as the working conditions were, and as meager the pay of the average worker, there was a larger issue at stake, Brandeis said. “The question here is not so much the question whether the number of cents per hour that this miserable creature receives is a little more or a little less. Whether it is enough, none of us are competent to determine. What we are competent to determine, sitting right here, as American citizens, is whether any men in the United States, be they directors of the steel corporation or anyone else, are entitled and can safely determine the conditions under which a large portion of the American people shall live; whether it is or is not absolutely essential to fairness, for results in an American democracy, to say that the great mass of working people should have an opportunity to combine, and by their collective bargaining secure for themselves what may be a fair return for their labor.”

The touchstone of the progressive movement was democracy. The progressives extended democracy by winning approving of the Seventeenth Amendment, which mandated direct election of senators (previously chosen by state legislatures); by the inauguration of primary elections, which gave voters a larger say in the nominating process; and by the adoption in many states of the initiative and referendum and the recall of elected officials.

Brandeis proposed to extend democracy further, into the economy. “We cannot maintain democratic conditions in America if we allow organizations to arise in our midst with the power of the steel corporation,” he said. “Liberty of the American citizen cannot endure against such organizations.” The steel trust was the biggest threat to democracy but hardly the only one. The principle of industrial democracy must be ensured throughout the economy. “There is no hope for American democracy unless the American working man is permitted to combine, and, through combination and collective bargaining, secure for himself the rights of industrial liberty,” Brandeis said.

Brandeis had heard the complaints against unions: that they infringed upon the liberty of individual workers, that they fomented class warfare, that they fostered a caste system within the working class, favoring skilled workers over unskilled. “No one can be more conscious than I am of the abuses of trade organizations,” he said. “Their acts are in many instances acts to be condemned, to be opposed, acts to be suppressed.”

But the sins of labor weren’t labor’s sins alone. “They are like all the abuses of liberty with which we are familiar,” Brandeis said. “We must maintain liberty, political liberty in spite of its abuses, and we must maintain the liberty of combination, and encourage combination on the part of unions, but hold them up to a high responsibility of using well that power which is entrusted to them.” Indeed, said Brandeis, merely recognizing the right of labor to organize would go far toward curing the abuses. “If we once come to a time where, instead of fighting for their existence, their existence is assured them, and they fight only for their rights, a large part of the abuses of which we complain today on the part of organized labor will cease.”

Brandeis’s call for democracy in the economy helped inspire Congress, during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, to establish the Federal Trade Commission, tasked with policing competition and punishing actions that subverted it. Brandeis’s efforts also won him appointment by Wilson to the Supreme Court, where he still sat in the 1930s when Congress approved the National Labor Relations Act, guaranteeing workers the right to unionize.

Yet the fight for economic democracy never ended. After a halcyon period during the generation after World War II, labor unions began to lose their hold, commencing a decline that lasted into the twenty-first century. Though Brandeis was long dead, his spirit lived on in a school of economists and policy advocates who called themselves “neo-Brandeisians” and made the same arguments against Amazon and Facebook that their namesake had leveled against U.S. Steel.

(See also https://hwbrands.substack.com/p/bork-v-brandeis)