The great majority of rulers in recorded history have been men. Given that men represent just half the human population, they are vastly overrepresented in leadership ranks. Why is this so?

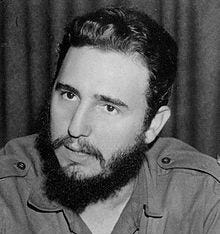

Revolutionaries throughout history have tended to be younger adults rather than older ones. Fidel Castro was 27 when he proclaimed his intention to overthrow the government of Cuba. No one thought his age unusual. Benjamin Franklin was 70 when he signed the American Declaration of Independence. Many people did think his age unusual. Why does revolution appear to be a young person's enterprise?

The best athletes in any sport tend not to become the best coaches. Indeed, the best coaches very often were mediocre players. What accounts for this?

Various answers to these and similar questions have been offered over the centuries. In olden times rulers were often the chief warriors of a tribe or people. Men, who on average are physically stronger than women, had an advantage on the field of battle. Yet the overrepresentation of men in leadership persisted long after kings were expected to lead their troops into battle personally.

The flip side of this same argument notes that women are able to bear children, while men are not. The survival of a band or tribe required not risking this unique ability unnecessarily. To lose a warrior on the field of battle was a misfortune. To lose a potential mother was a calamity.

These answers are essentially biological. But culture obviously has had an influence. A practice once established tends to stay established. Those who benefit from a practice have a vested interest in preserving it. Male rulers liked the idea of ruling and promoted ideologies that kept them on top. “We've always done it this way” is an argument that is logically suspect but often persuasive.

In modern times the overrepresentation of men in leadership positions has become attenuated. Is this due to biology or culture? Is modern leadership more a function of character traits that men and women share more equally? Or have humans changed their minds and decided to give women a fairer shake in politics?

About those revolutionaries: Are younger people inherently more impatient than older people? More idealistic? Do these traits naturally diminish with physical age? Or is it the case that older people have learned through experience that change is difficult and unpredictable and that revolution is often not the best solution to social problems?

Clearly the ability to swim fast is distinct from the ability to teach and motivate someone to swim fast. Is there something biological that tends to prevent these separate abilities from appearing together in single individuals? Or is there something cultural that spurs less gifted swimmers to focus their energies on developing coaching skills?

The answers to these questions, predictably, is a little of each. Biology has something to tell us, but so does culture.

If these questions resided solely in the realm of philosophy or mere curiosity, this ambivalent answer would suffice. But the questions have long been posed in the realm of politics. And politics abhors ambivalence. Partisans want actionable answers.

As a rule, defenders of the status quo have favored biological explanations for observed differences. When only men could vote, it was common to hear them say that women were less intelligent, at least on subjects under discussion in politics. Colonialists justified their dominion on grounds that the peoples being colonized were inherently unable to govern themselves.

Biological explanations have the advantage, for defenders of the status quo, that from the human time scale, biology is largely immutable. Attempting change, therefore, is a fool's errand.

Conversely, challengers to the status quo typically favor cultural explanations. These have the advantage of being subject to change within any given lifetime. If women don't know as much about politics as men, that's because they're not educated as men are educated. Educate the women, and they will be as capable of political participation as men. The reason colonized people aren't good at self-government is they've never had the opportunity to govern themselves. Give them a chance, and they will learn.

Historians, as historians, needn't choose sides in the debate between status quo and change. Indeed they probably oughtn't choose sides. They can best promote human understanding by investigating the general relation between nature and nurture in the past with open minds.

For those historians who work in the academic world, this can be risky business. When Larry Summers was president of Harvard, he mused, in what apparently was a spirit of open-minded inquiry, whether the larger proportion of men than women in the natural sciences might reflect innate differences in the distribution of certain intellectual traits between men and women. Summers is an economist by training. He seemed to be thinking in statistical terms. The median IQ — to oversimplify — of men and women might be the same. But the bell curves that produce the same median might have different tails, with more men at the extreme low end and more at the extreme high end. People who become academic scientists are taken from the high end of the distribution and there might be more of these among men than among women.

He presented the question as worth considering. His audience didn't consider it worth considering at all. He was roundly denounced for suggesting any such thing. Most of the critics presented no evidence and didn't want even to entertain the possibility he floated. They simply assumed that the comparative dearth of women is due entirely to discrimination.

Maybe it is. But it shouldn't be taken as an article of faith. It should be demonstrated with evidence.

Whoa! You're cruisin' for a bruisin' as my grandmother used to say ;-)

I just finished Founding Partisans and it put a lot of things in perspective for me. I was shocked at the heavy handedness employee to deal with major protests and the Sedition Act. Libertarians like myself would have been appalled.