Time is a conundrum. It puzzles even physicists, for whom it is a foundational concept. Einstein wrote it into his description of the universe, as a fourth dimension after length, width and height. This made the calculations easier, but it didn't necessarily yield insight. The three ordinary dimensions are observably reversible. I can go forward and back, left and right, up and down. But time appears to permit one direction only—toward the future. No one has figured out how to go back in time.

Time is as foundational for historians as for physicists. And it is often as puzzling. We go backward in time, in our research and our imaginations. We sometimes wish we could go backward in time physically, to clear up a question our research leaves unanswered. What was Cornwallis thinking in letting himself be trapped at Yorktown? I'd love to be able to ask him.

Just as every person is an amateur physicist, everyone is a historian. I don't jump off cliffs because I know about the law of gravity. I form a mental model about the past, because without it I wouldn't be able to operate effectively in the present. On federal holidays in America, banks are closed. They have been for many years. So I won't expect my bank to be open next Fourth of July.

Two mental models have predominated in thinking about history. One is linear, the other cyclical.

In the linear model, history moves in a single direction. This direction has been characterized variously: toward greater complexity, toward a higher state of civilization, toward the fulfillment of religious prophecy, toward inevitable demise. Observations of the past have been adduced to support the different characterizations. Urban life in China at the beginning of the 21st century certainly seemed more complex than village life in China had been been five centuries before.

The characterizations could be self-serving. People who spoke of “higher civilization” generally placed themselves on the upper rungs. People who looked to the fulfillment of religious prophecy typically reckoned they were among the saved.

These observations demonstrate that a conception of history's direction is as much about the future as about the past. Knowledge is power, and no knowledge is more powerful than that which foretells the future. If I spot a trend in the stock market before others do, and if that trend continues into the future, I can become rich. If I correctly project political trends from the past into the future, I can jump aboard the winning party and get a plum job in the next administration. If the end is indeed nigh, a timely repentance can save my eternal soul.

The second common model of history is the cyclical one. History moves not in a straight line but in a circle. Patterns repeat. An empire rises, then it falls. A new empire rises, then it too falls. Economists speak of the business cycle. A shortfall of product causes prices to rise. Rising prices prompt producers to increase output. Collectively they overshoot the mark, and their excess production causes prices to fall and some producers to fail. The reduced output makes prices rise again, and the cycle repeats.

The linear model of history appeals to cultures that value the idea of progress. History has a direction, and the measure of a culture, society or nation is the progress it makes in that direction. Cultures that are part of the Abrahamic tradition of religions—Judaism, Christianity, Islam—lean toward the linear view, for in each religion adherents believe that the world unfolds according to God’s plan. The plan commenced with the creation of the heavens and the earth. It did or will proceed with the coming of the Messiah. It will culminate in an end time when the dead will be resurrected and the world finally perfected.

Other cultures are more comfortable with a cyclical view of things. The Chinese calendar embodies twelve-year cycles. Chinese historians developed a theory of government based on dynastic cycles under the “mandate of heaven,” which provided legitimacy when governance was good but was withdrawn when rulers grew corrupt. Chinese philosophers saw the cosmos as moving through cycles of yin and yang, representing different kinds of energy and force.

Hindu thinkers placed individual lives in the context of an eternal cycle of life, death and rebirth. Most people would pass through many incarnations. The fortunate would finally escape the cycle by achieving the transcendence of moksha.

As the Hindu example reveals, the linear and cyclical models needn’t be mutually exclusive. When joined, the combination can be represented not separately by a straight line or a circle but by a hybrid cycloid, which is the path of a point on a wheel as the wheel rolls down a road. From the frame of reference of the wheel itself, the point’s motion is cyclical—to wit, circular. But from the frame of the road, the point makes longitudinal progress.

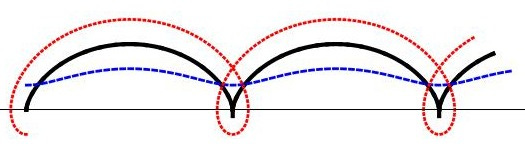

Cycloids come in varieties. If the point is on the rim of the wheel (in black above), the linear motion halts when the point touches the road. It then speeds up, reaching a maximum when the point is farthest from the road. If the point is near the axle (blue), the linear motion merely slows and speeds up. If the wheel is a railroad wheel and the point is on the flange that extends beyond the rail (red), the point goes backward periodically.

This sounds complicated. But history is complicated, and the different cycloids show how the linear and cyclical models apply in the real world. Lots of things are cyclical—days, seasons, ice ages, political campaigns, epidemics—but they never return the system to the exact place it started. There’s always some linear motion, if only because the rest of the cosmos has changed while the observed cycle was completing its turn.

This is what makes using history to predict the future at once tempting and dicey. The cyclical aspect of history makes us look for similarities between the past and the present. We can always find something. But the linear aspect of history means that the present is not exactly like the past. The wheel has moved down the road. We can’t be sure in advance whether the similarities with the past, or the differences, will be decisive.

So we have no choice but to roll along as best we can.