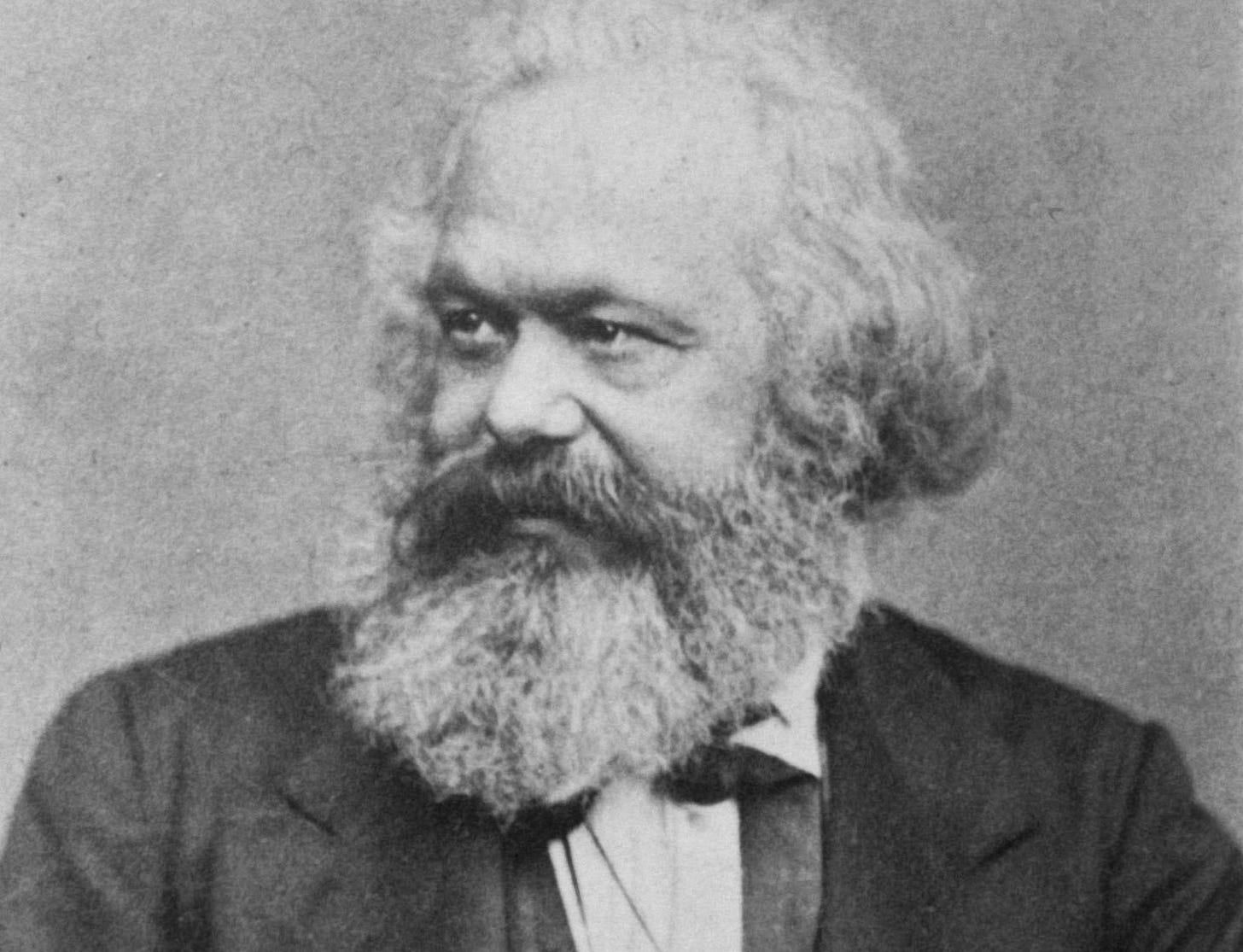

Karl Marx was a matter-of-fact historian. Which was to say he emphasized matter and facts in his study of history. People fought over the everyday stuff of life, he said. “The history of all hitherto existing human society is the history of class struggles,” he wrote in 1848. And what the classes struggled over was the means of production: that which created material wealth in societies.

The big story of European history in the middle of the 19th century was the emergence of industrial capitalism. This new phenomenon had arisen from the contradictions of feudalism, Marx said. A new class of merchant property owners, the bourgeoisie, had burst the chains of feudalism and seized control of the levers of government power, which they now operated to their own benefit.

Marx's materialist interpretation of history challenged the liberal idealism associated with the Whig party in Britain, to which Marx was about to flee. The Whig idealists, taking their cues from the Enlightenment of the 18th century, interpreted history as the unfolding of the ideas of human freedom articulated by the likes of John Locke, Jean Jacques Rousseau and Thomas Jefferson. The American revolution, the French revolution, the numerous revolutions in Spanish America, the Greek revolution, and the 1848 revolutions in progress at the time of Marx's writing were attempts to put the formulas of “life, liberty and property,” "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” and "liberty, equality and fraternity” into practice.

In certain respects the split between Marx and the Whigs went back to the debate between Aristotle and Plato over substance and form. It was refracted through the musings of Descartes on the distinction of body and mind. More than a few historians were willing to have a foot in each camp. Man does not live by bread alone, as Moses and Jesus said. But without bread man does not live at all.

If Marx and his opponents had been content to be mere historians, such a compromise might have been acceptable. But they were political activists as well. The class struggle wouldn't stop at capitalism, Marx predicted. Indeed it was in the process of producing socialism, which would result when the industrial working class, the proletariat, overthrew the bourgeoisie and took control of the state. This was inevitable, Marx said, and it would be a blessing to humanity.

The liberal Whigs wanted none of this. They were the bourgeoisie, and they didn't fancy being overthrown. History would continue to unfold not through Marx's socialist revolution, they said, but through incremental improvements in the existing status quo.

The future proved both sides partly right. Socialist revolutions succeeded in Russia, China and some smaller countries, although Marx might not have recognized the leaders of these revolutions, who were rarely card-carrying members of the proletariat. In the most fully industrialized countries, where Marx thought the revolution would occur first, a Whiggish evolution forestalled socialist revolution.

Yet historians should be judged not by their predictions of the future but by their explanations of the past. The question remains whether the materialists or the idealists have the better of the historical argument. Put otherwise, if you had to explain the history of the world in five minutes, would you focus on what people did or what they thought?

You might object that this is a false dichotomy. People can't act without thinking. You might also object that this gives the advantage to the materialist side. It's easier to demonstrate what people did than what they thought. Conversely, you might object that this gives the advantage to the idealists. Historians are beguiled by the written record. The written record is skewed by what people in power said and wrote. And people tend to put the most positive gloss—which often means the most idealistic interpretation—on their actions.

On this point modern technology might be helpful. Traditional memoirs were sometimes self-consciously written to influence future historians. Some still are. But it's impossible to maintain a consistent false persona in everyday emails, texts and phone calls. Just as no one is a hero to his valet, no one can escape the indefatigable scrutiny of the cloud. Future historians will know more about their subjects than the subjects themselves did.

This won't resolve the underlying question of materialism versus idealism, which like most questions of philosophy is ultimately unresolvable. History is, among other things, applied philosophy.

Nevertheless, pursuing the question thoughtfully will shed additional light on humans and our behavior, which is the point of the whole exercise.

As a historian, I am very pleased you wrote this post. Yes, history is applied philosophy. Well put.

Same as above!