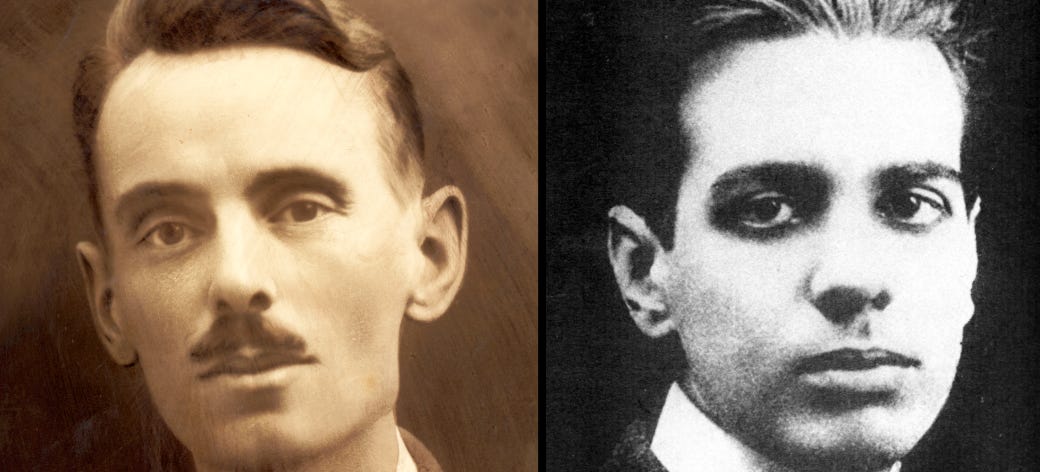

In 1913 a French mathematician named Emile Borel proposed a thought experiment: “Let us imagine that one has trained a million monkeys to strike the keys of a typewriter at random and that, under the supervision of illiterate foremen, these typing monkeys work industriously ten hours a day with a million typewriters of various models. The illiterate foremen would gather the blackened pages and bind them into volumes. At the end of a year, these volumes would be found to contain the exact copy of books of every kind and in every language preserved in the richest libraries in the world.”

In 1941 Argentine author and librarian Jorge Luis Borges employed a similar idea in his short story “The Library of Babel.” There were no monkeys in Borges’ library, just books of the sort they would have produced. “Its bookshelves contain all possible combinations of the twenty-two orthographic symbols (a number which, though unimaginably vast, is not infinite)—that is, all that is able to be expressed, in every language. All—the detailed history of the future, the autobiographies of the archangels, the faithful catalog of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogs, the proof of the falsity of those false catalogs, a proof of the falsity of the true catalog, the gnostic gospel of Basilides, the commentary upon that gospel, the commentary on the commentary on that gospel, the true story of your death, the translation of every book into every language, the interpolations of every book into all books, the treatise Bede could have written (but did not) on the mythology of the Saxon people, the lost books of Tacitus.”

At the time of their writing, many readers thought the scenarios described by Borel and Borges intriguing but of course unworkable. Borel’s monkeys produced and Borges’ Babel comprised all the good stuff of literature but at the cost of mountains of dreck. The latter would so overwhelm the former that the good stuff could never be found.

Times have changed. Artificial intelligence could handle the sifting a billion times faster than humans. After Borel and Borges, the thought experiment was commonly modified to posit an infinite number of monkeys typing forever. In this version, the sifting of the whole output would take infinitely long, even for AI. But we could make a start by dealing with finite portions of text. It wouldn’t take forever for the monkeys to type “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” Nor forever for AI to find it. The forty-eight thousand words of The Great Gatsby would take longer, but again not infinitely longer. Likewise for any other single work of literature.

What if we circumvented the monkeys? What if we let AI do the writing?

This would save a lot of time, in that AI would confine itself to strings of letters that form actual words, unlike the illiterate monkeys. Not only that, but the words would parse as sentences. And the sentences would hang together as paragraphs.

Would the paragraphs have meaning?

They certainly would have as much meaning as anything produced by the monkeys. The meaning of a sentence or a paragraph depends on the reader as well as on the writer. “All the world’s a stage”—does this mean reality is a play, or that plays are reality? Shakespeare lets us have it both ways.

Shakespeare intended something with his writing. Does AI intend anything? Maybe not. But neither did the monkeys. And yet they wrote As You Like It.

What about hallucinations, those infamous artifacts of AI production?

Here’s where AI shines, so long as we’re talking about fictional literature. In this context hallucinations aren’t a bug but a feature. Hallucinations are the AI version of originality. The defining characteristic of a novel or a play is that the novelist or playwright—or AI—made it up.

Yes, but what the novelist or playwright made up works only if it seems true to life.

Here again AI shines. The reason its hallucinations are so vexing in law briefs and dissertations is that they’re plausible—plausible enough to slip past proofreaders.

Over the centuries human users of hallucinogens have sometimes thought the drugs enhance creativity. Others have been dubious.

AI doesn’t need drugs to hallucinate. It does so unaided. Many find its hallucinations infuriating. Some judge them creative.

AI has been with us only a short time. We should let it work longer. Not forever. Nobody can wait that long. But a while.

Claude, Gemini, GPT, Llama: Type away.

Well, I will have to revisit Borges. Anybody other than a theologian or historian of religion who knows who Basilides is deserves a second look. For myself, however, Terminator ruined my appreciation for anything like AI.

Quite a thoughtful post. As someone coming of age in this new world of Artificial Intelligence, I often find myself tempted to mingle in this creativity, only to feel morally guilty at the mere suggestion that I could lend my writing to AI on a creative and thoughtful prompt. Future students may not share my same sentiment.