Before their time

Ranked-choice voting in the Constitution

Hoping to ease the election of centrist candidates, good-government groups have pushed the adoption of ranked-choice voting, which allows voters to select more than one candidate on a ballot. If no candidate wins a majority of first-place votes in the initial round of tallying, the one with the fewest is eliminated, and ballots with his or her name at the top have their second choice consulted. This process continues until a single candidate emerges at the top of a majority of ballots.

The idea is that in our existing system, zealous minorities in each party are over-represented. Moderates get pushed aside, leaving centrist voters no one to vote for. By allowing candidates who might be the second or third choices of a lot of voters to rise to the top, ranked-choice voting (also called instant-runoff voting), encourages candidates to appeal to the broad middle rather than the narrow fringes. A few states have adopted ranked-choice voting for some elections. More than a dozen are considering it.

Almost none of the advocates of ranked-choice voting—or the opponents, for that matter—realize that a variant of it was written into the federal Constitution of 1787, and for no less an office than the presidency.

The original wording of Section 1 of Article II said that “the electors shall meet in their respective states and vote by ballot for two persons.” That is, each elector had not one vote but two. “The person having the greatest number of votes shall be the President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of electors.” If no one received a majority, the race went to the House of Representatives. The second-place finisher in the voting for president became vice president.

This system didn’t have the instant-runoff feature of modern ranked-choice voting, but it did share a fundamental expectation: that while none of the favorites of voters might command a majority, their second-choices might.

The thinking at the Constitutional Convention was that electors would probably use one of their ballots for a favorite son of their state or region. None of these candidates would receive votes from more than half the electors. The second ballot of the electors would be used for a candidate with broad appeal. This candidate would, in most cases, get votes from more than half the electors and would become president.

The system worked well in the first election, in 1789. A dozen candidates received electoral votes. George Washington received a vote from every elector, making him president. The outcome is often described as a unanimous victory for Washington. This isn’t strictly true, as half the electoral votes went to other candidates. Did any of the electors prefer John Adams, the second-place finisher, to Washington? It’s not impossible, but we can’t know for sure, as the system didn’t distinguish between the two ballots of each elector. In any event, Adams’s 34 electoral votes, after Washington’s 69, made him vice president.

The second presidential election, in 1792, proceeded as smoothly. Five candidates received electoral votes. Washington again got a vote from every elector and retained the presidency. Adams again came second and retained the vice presidency.

The third president election, in 1796, was the first without Washington, who chose to retire. It was also the first in which political parties played a role. The Federalists had coalesced around the big-government, pro-British thinking of Alexander Hamilton, although Adams made a more appealing candidate than the arrogant Hamilton. Thomas Jefferson led the Republicans, who distrusted government and favored France. The two sides paired candidates for president and vice president. Most of the Federalists intended their electors’ ballots to make Adams president and Thomas Pinckney vice president. There remained no distinction between president and vice president on the ballots; the Federalists arranged for some of the Federalist electors to cast their non-Adams ballot for someone besides Pinckney. This was tricky to pull off, for if the overall race was close, Jefferson might slip into second place in the voting, behind Adams and ahead of Pinckney.

Which was precisely what happened. Adams got 71 electoral votes, Jefferson 68 and Pinckney 59. So Jefferson, Adams’s rival, became Adams’s vice president.

An awkward four years followed. In later decades vice presidents often seemed to do nothing; in the 1790s, Jefferson did worse than nothing, from Adams’s perspective. He consistently opposed Adams and organized other Republicans to do the same.

Jefferson’s sabotage succeeded well enough for him to defeat Adams in a rematch election in 1800. But he didn’t defeat Aaron Burr, his running mate, at least not at first. The Republicans were well organized, agreeing on Jefferson for president and Burr for vice president. Indeed they were too well organized, voting in lockstep for Jefferson and Burr; and because the ballots didn’t distinguish between president and vice president, Jefferson and Burr wound up tied for first—that is, tied for president.

This sent the contest to the House of Representatives. The congressional elections that accompanied the presidential race had delivered a majority in the House to the Republicans, but until the new members were sworn in, the Federalists controlled the chamber. This meant that the Federalists would choose which Republican—Jefferson or Burr—would be the next president. The Federalists finally chose Jefferson, but not without much finagling and not before nasty things had been said about Burr by Hamilton—things that contributed to the duel between Hamilton and Burr in 1804 that cost Hamilton his life.

Ironically perhaps, Hamilton died just weeks after the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment, which eliminated the electoral confusion that contributed to the duel. Each elector still cast two ballots, but one was specifically for president and the other for vice president. This is the system we have today.

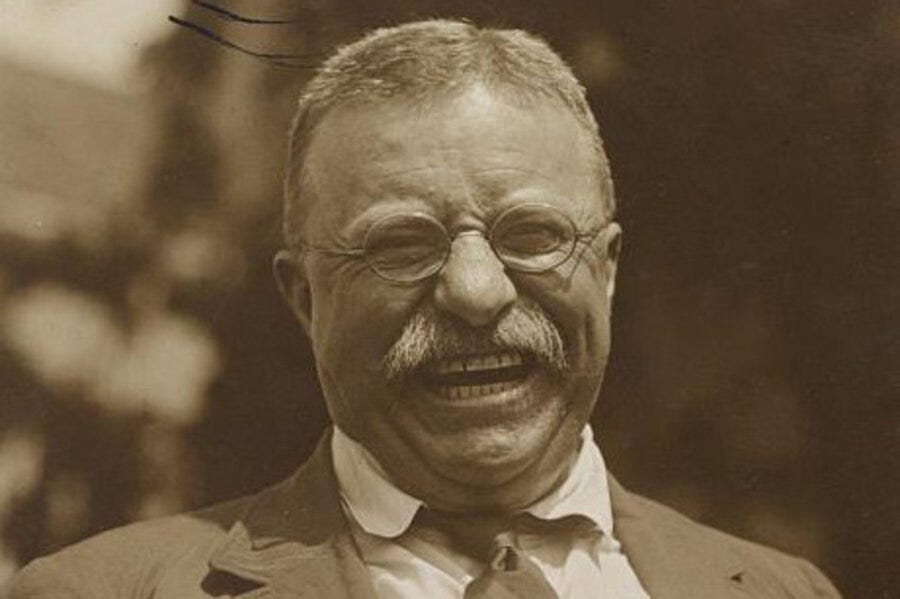

Suppose, for the sake of history if nothing else, that we still had something like the original method of choosing the president. If applied directly to the electoral vote, this would have little effect, given that electors typically vote as blocs by state. But if applied to the popular voting within the states, it could have a big effect. Take the 1912 election. Nearly every Woodrow Wilson voter likely preferred Theodore Roosevelt to William Howard Taft. And nearly every Taft voter preferred Roosevelt to Wilson. Wilson carried 27 states without popular majorities there. In instant runoffs in those states, Roosevelt would have received Taft’s votes, which would have won him sufficient states to win the election.

Roosevelt’s example might have encouraged other third-party candidates. Such candidates are generally spoilers in our present system. Jill Stein’s candidacy perhaps cost Hillary Clinton the 2016 election. And Gary Johnson came close to costing Donald Trump the election. In a ranked-choice regime, the spoiling effect would vanish. Votes for Stein would have gone to Clinton (almost certainly) in the second round, and Johnson votes would have gone to Trump. Voters, knowing that, would have felt freer to vote their consciences, which is a good thing in itself. The fresh thinking third and fourth parties bring to a campaign is a good thing too.

It’s not going to happen. One of the few things the two major parties agree on is the need to stifle third parties. And the Constitution has become prohibitively difficult to amend. Yet it’s still intriguing to note that the framers of the Constitution anticipated by two centuries a line of thought of modern reformers. Good ideas come and go, and sometimes come again.

That's the weakness of the American system. Third parties outside of the mainstream have made significant progress everywhere in the world except America.

On further thought on the "stifle" assertion. As I noted before, having run for Congress and also staying involved since,. the so-called third parties simple don't DO THE WORK. They don't canvass, knock on doors, etc. Speaking from experience, the Democratic Party county and district organizations go all out handing out literature, knocking doors to speak to voters- Our couny party is fully active and organized in this manner.

From where I sit, the third parties such as Libertarians and Greens simply toss candidates onto the ballot and then fade away until the next election.

And for the most part, most of the Green party platform is also present in much of the Democratic party positions anyway