AI will destroy your job

But don't worry; we'll find something for your kids to do

The most important development in the economic history of the human species has been a huge improvement in our ability to feed ourselves. From this, everything else follows.

Humans, like other animals, require a few essential items to live. We need air to breathe, water to drink, and food to eat. Originally these were all around us and were free for the taking. Air still is. Water was provided by the streams we lived near; it mostly still is. Food grew on trees and bushes and scampered within reach. This is where the big changes occurred.

The first step in the food revolution was the development of tools: sticks to dig up roots and rocks to throw at squirrels. A second step was the use of fire, which by roasting the roots and cooking the squirrels made their nutrients more available to our digestive systems.

In time came agriculture. The clever among us learned to take seeds from edible plants and bury them in locations where they could be conveniently tended and safely harvested. We got better at this until we produced a surplus that allowed some of us to do other things.

It was the freeing of humans from the constant struggle for food that formed the basis of civilization as we know it. Some of us became priests. Some became poets. Some became soldiers, Some became kings.

Jump forward to around 1850. Most humans still worked in food production, typically on farms. But again emerged some clever people among us who this time applied the power of fossil fuels to the production of food. During the next century, the proportion of humans required to feed the species fell to ten percent, then five percent, and in some countries as low as one percent.

Every time food production became more efficient, in theory those of us who didn't have to work to furnish food could have sat around and enjoyed our leisure. If we had persisted in this approach, by the late 20th century only 1 of 100 of us needed to work. The rest of us could have lazed all the time. Or we could have toiled in turn, working 1 day and taking 99 days off.

In earlier times we didn't have to become priests and poets and soldiers and kings. Humans don't need people in those capacities for our species to survive. Or at least we didn't at the beginning. Yet the same inquisitiveness that gave rise to the first improvements impelled us to explore our environment. Some of us moved to places where fruit didn't hang on the trees and where our tools and techniques became essential for our survival. We pushed into new climate zones that required us to clothe and shelter ourselves. Thus tailors and masons became as necessary as food producers. In our expansive activities, we bumped into other groups that contested our expansion. And so we needed soldiers and kings.

Summing up, the original AI—agricultural intelligence—destroyed the jobs of 99 percent of us. But in doing so, it created needs our ancient ancestors didn't have and couldn't imagine. We learned to fill those needs by devising new jobs.

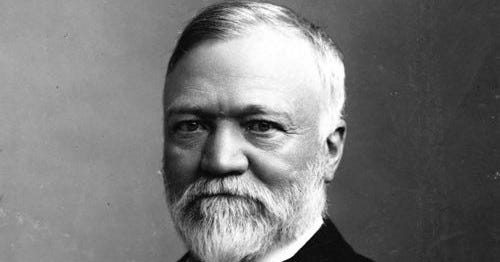

The process wasn't smooth or comfortable. Very often the people who lost jobs never found comparable new ones. But their children did. A spectacular example involved Andrew Carnegie. His father lost his job as a textile worker in Scotland. He couldn't find another job there, and the family moved to America. Even in America he never found anything like what he’d had before. But his son became the great industrialist of the age. Needless to say, not every story turned out so happily. But enough did that America moved forward, with each generation enjoying a higher standard of living than generations before.

The modern AI—artificial intelligence—is likely to have similar effects. It might not destroy the jobs of 99 percent of us, but within the next generation or two it will be able to do a large portion of the work that is being done by humans today. It already writes news stories badly; it will get better. It already reads x-rays and MRI scans very well. Almost certainly it will put drivers of trucks and taxis out of business. It's not far-fetched to say it will do the same to airplane pilots—first the pilots of cargo planes but eventually the pilots of passenger planes as well. It's already writing novels and movie scripts and will get better at these. The turning point in this area will come when blind tests show that critics and reviewers can't tell AI work from human work. AI will make surer diagnoses than human doctors. AI will write more cogent legal briefs than human lawyers. AI will be a more patient teacher than human teachers.

What, then, will all the people displaced by AI do? The displaced themselves will probably be as discombobulated as Andrew Carnegie's father was. They might never recover. But their children and grandchildren will take up newly imagined and created jobs.

Or maybe they won't do anything at all. Maybe they'll just let the robots do the work. Except that we never did this in the past when economic change gave us the opportunity. We humans like to keep busy. We’ll find something.