Judge not, that ye be not judged.

Jesus' advice was good, but it could have been better. He might have left off the that-ye clause. "Judge not" is good counsel on its own. It's presumptuous to judge other people. What do we know of their lives, their burdens, the constraints on their choices?

Judging is unavoidable in certain circumstances—courtrooms, gymnastic meets, county fair bake-offs. Judging is often tied to choosing. I choose this job because I judge it preferable to the alternatives on pay, working conditions, opportunities for advancement. I choose this person over others for a mate because I judge this one most appealing physically, intellectually, temperamentally, morally. In such cases judging serves a specific purpose.

But when judging is unattached to a necessary decision—when it shades into judgmentalism—it can easily become pernicious. Teenagers are notoriously hard on themselves. They tend to think everyone else is better looking, smarter, more popular than they are. They think the world is scrutinizing them and they are coming up short. One reason adduced by psychologists for the angst among teenagers today is the impossibility of measuring up to the ideal images they see on social media—images that are often doctored to look better than any actual human could be.

Where judging makes teenagers feel unwarrantedly bad about themselves, other forms of judging make people feel unwarrantedly good about themselves. This kind of judging is often at the expense of other individuals or groups, and the feeling of superiority it engenders is the purpose of the exercise. If I and the members of my clan, tribe, race, religion, nation, civilization judge that we are superior to your clan etc., that judgment fosters cohesion which helps me and mine defeat you and yours in the contests that arise for resources necessary to survival. Evolution has certainly selected for such common feeling, which explains why it is ubiquitous among humans.

Some groups in recent decades have tried to distance themselves from particular aspects of this judgmentalism. Western liberals consider it gauche or much worse to admit liking people of their own religion, race or nationality better than others. But for most of history this was considered unexceptional—indeed, it was expected and praiseworthy. In much of the world today it still is.

Liberals get upset at judgments made about other people in the present, but they are often eager to pass judgment on people who lived in the past. Indeed, they demand that judgments be made about those past folks. And the sterner and less nuanced the judgment the better. Sidney Lanier was a poet who had a school named for him in Austin on account of his poetry. But in young adulthood Lanier had served as a private in the Confederate army, and for this failing he was struck from the school's marquee in 2019.

John James Audubon was the founding father of American ornithology. His name was on parks, wildlife refuges and birding societies across America for more than a century. But Audubon had owned slaves, which fact finally condemned him in the judgment of some who had capitalized on his fame and accomplishment. The Audubon Union, a workers’ group associated with the Audubon Society, changed its name, declaring, “We will not elevate and celebrate a person who would reject and oppress our union members today." Lest anyone mistake their performative presentism, the workers explained, “Changing our name is a small step to demonstrate our commitment to anti-racism.”

Besides making themselves annoying, people who indulge such judgments deprive themselves of the principal value of history. An open-minded study of the past allows us to expand our understanding of what it means to be human. By contrast, a close-minded view of history—the view produced by the judgmental mindset—shrinks our understanding. We can't see what lies outside the field of vision of today's tastes and values. Judgmentalism makes us feel good about ourselves, but in the same way racists and xenophobes feel about themselves: by denying the human equality of those who aren't in the group doing the viewing.

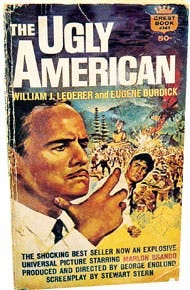

A stock character in particular genres of literature is the ugly American or the bumptious John Bull: the know-it-all American or Brit who travels the world and learns nothing, so full is he of his nationalist self. The judgmentalists play the same role with respect to history. They roam the past but never leave their bubble of presentism. They would have been better off staying home.

Brands' example of Sidney Lanier High School in Austin having its name changed because Lanier had served in the Confederate army in his youth is a good example of political correctness running amok. It's the American equivalent of damnatio memoriae in Roman times. I once asked a professor the following: If we're going to remove Confederate statues and rename schools, what about George Washington? Her answer was to ask what a historical figure is known for. We revere Washington as the founder of our country, not as a slaveowner. Well, we remember Sidney Lanier as a poet, not as a soldier of the South. I wish the statue removers and name-changers would at least be consistent.

Fantastic! This is in fact the core principle of my humble podcast.