A perfect storm

American politics since the 1960s

Big events in history typically have multiple causes. The industrial revolution reflected changes in technology, economics, politics, education, culture and other aspects of human existence. Global climate change involves meteorology, chemistry, physics, demography, geography, oceanography, psychology, sociology and more.

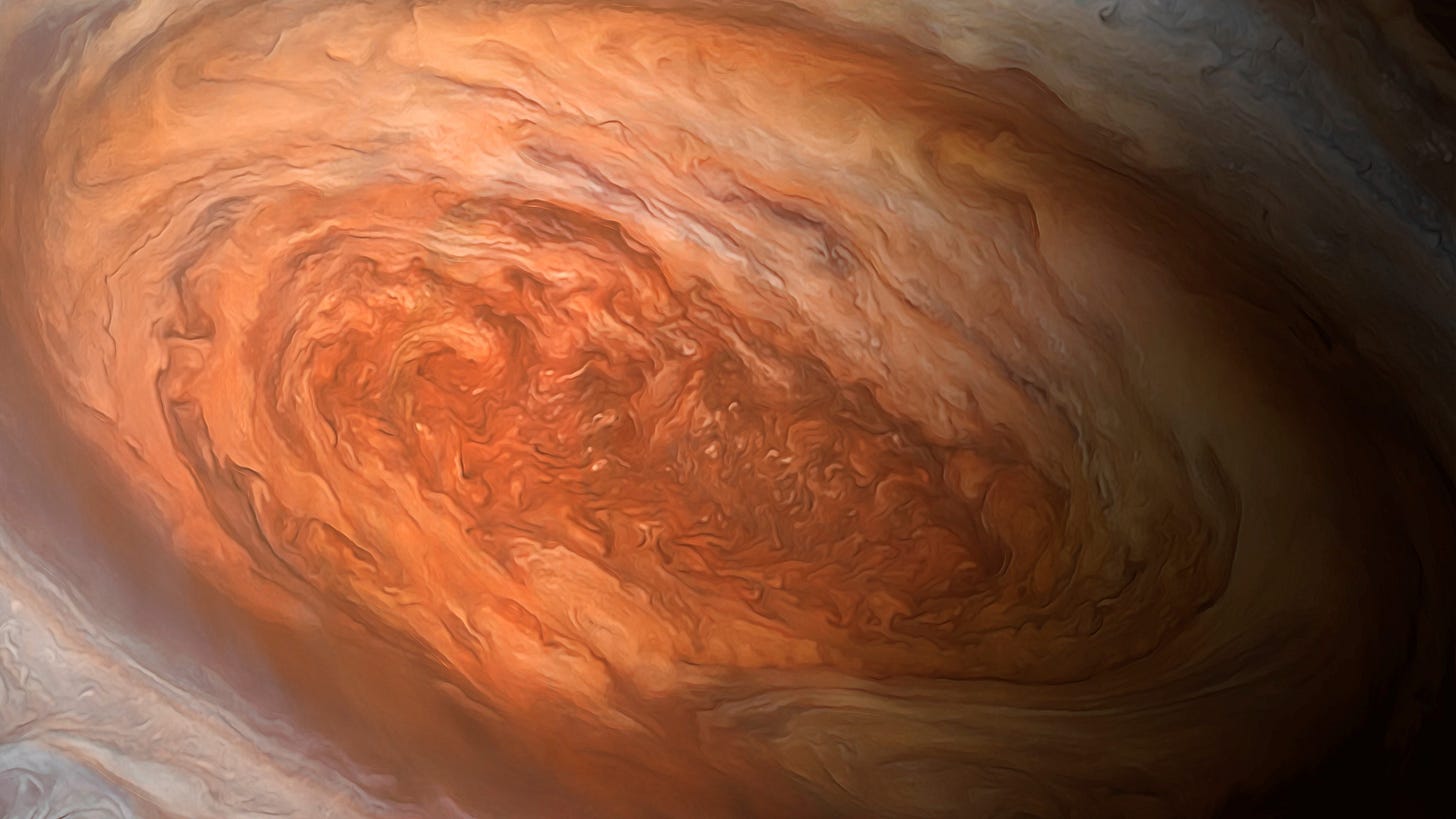

The great change in America's political climate in the last half century, the development of a partisan tempest that, like the Great Red Spot of Jupiter, doesn't seem to move much and doesn't go away, similarly had several causes.

First and most obvious was the decision by Lyndon Johnson to make civil rights the priority of his administration. Johnson's decision exploded the coalition of urban liberals and southern conservatives on which the Democratic party had rested. Southern conservatives, some opposed to any changes in race relations but nearly all opposed to changes imposed by the federal government, took Johnson's action as a signal that the Democratic party could no longer be their home. The older ones simply stopped voting for Democratic candidates, younger ones formally flipped from the Democratic party to the Republican, and the youngest never joined the Democrats in the first place. The transition took a generation, but by the mid 1990s it was essentially complete. The South, solidly Democratic in living memory, became reliably Republican. And so it remains.

The second cause was a consequence of the first. As southern conservatives invaded the Republican party, they displaced liberals there. Some of these liberals were grandchildren of the Lincolnian founders of the party, some were children of Teddy Rooseveltian progressives, and some simply had an aversion to the Democratic bossism of the big cities in which they lived. As their party shifted to the right under the southern influx, they migrated to the Democrats.

The result of the dual migrations was a more perfect philosophical sifting of the two parties than had ever existed in America. American parties had always been as much about geography and history as about ideology. Those southern conservatives had been Democrats not because they liked what Franklin Roosevelt did in the 1930s, which they did not, but because they hated what Lincoln did in the 1860s. The consequence was that the right wing of the Democratic party overlapped the left wing of the Republican party. On crucial votes in Congress—on civil rights, for example—a Democratic president like Johnson could count on a substantial number of Republican votes. Similarly, before the partisan migration had finished, a Republican like Ronald Reagan could count on some Democratic votes on issues like tax reform and immigration. By 2000, the philosophical overlap had vanished. With rare exceptions, the most conservative Democrats were visibly to the left of the most liberal Republicans.

A third contributor independently amplified the second. The technology of cable television broke the triopoly of the three major networks as conveyors of political news. While that triopoly had existed, federal law had reasonably mandated political balance in broadcasts. If NBC aired a speech by a Democrat, it had to give equal time to a Republican. Cable television made this fairness doctrine obsolete. With hundreds of channels available to home viewers, balance was no longer required within a network because it was available across the spectrum as a whole. Conservatives could tune into Fox News, liberals to MSNBC. The internet lengthened the buffet table further. Social media created separate dining rooms. The effect spread to newspapers, which by this time were creatures of the internet as well. Liberals read the New York Times and the Washington Post, conservatives the Wall Street Journal. Given that liberals were now all Democrats, and Republicans all conservatives, the media world was effectively split along partisan lines.

A fourth factor applied specifically to presidential contests. After progressive Democrats were infuriated by having Hubert Humphrey foisted upon them at the Democratic national convention in 1968, and, crucially, after Humphrey lost to Richard Nixon, the Democrats revised their rules to give primary elections the dominant role in determining the party's nominee. The Republicans followed suit, in the name of heeding the will of the people. The result was that primary voters, the most zealous members of each party, became the gatekeepers to the general election. For a while this wasn't a particular problem. It was understood that candidates in primaries would appeal to the right wing of the Republican party and the left wing of the Democratic party, but then would hew to the bipartisan middle after receiving the nomination. But by the beginning of the 21st century, the middle had vanished. Adapting to circumstances, the nominees focused instead on energizing and turning out their base voters, reinforcing partisanship the more.

A fifth factor influenced congressional races but bled over into state contests. Computers made possible analysis of votes in a way that allowed state legislatures to gerrymander districts to the benefit of the majority parties. Gerrymandering was as old as Elbridge Gerry, its founding father namesake, but in the late 20th century it became a surgical tool for sculpting districts that yielded automatic victories for the designated parties. When Republicans controlled a state, they would pack Democrats into as few districts as possible and spread out the Republicans. Conversely when the situation was reversed. The upshot was to shift the competition from the general election to the primaries, where, again, the zealots ruled. A Republican member of Congress tempted toward bipartisanship understood that he or she would be challenged from the right in the next primary; most resisted the temptation. Likewise for Democrats from the other direction. As in everything else, partisanship won out.

A sixth factor was the partisan mobilization of evangelical Christians. Until the middle of the 20th century, religious denominations in America tended to be oriented toward issues rather than parties. Some of this reflected the ideological ambiguity of both parties until then. Catholics were always against abortion, Baptists often against liquor. Each group would support whichever candidates sided with them, regardless of party. But as the parties sifted out, they took the issues with them, and denominations followed.

Democrats became the party of abortion rights, making it more difficult for them to attract Catholic votes. Yet Catholics for decades had been a beleaguered minority in America and even in the late 20th century they hesitated to mobilize politically as Catholics.

Less reluctant were evangelical Christians. As Protestants they were firmly in the American mainstream. Indeed, many felt they were the mainstream, or at least had been and still should be. Cultural changes coming out of the 1960s and 1970s caused many of them to feel alienated. Most were stoutly opposed to abortion, but also to gay rights and changing roles for women. The large number of evangelical Christians living in the South had previously been conflicted by their legacy membership in the Democratic party, which generally favored the cultural changes the evangelicals disliked. But that conflict diminished as most southern conservatives, including many evangelicals, abandoned the Democrats for the Republicans. Their new home made political activism more straightforward.

Here the changing media environment contributed as well. There had been radio preachers in the 1930s, but the television evangelists—televangelists—of the 1970s carried their version of the gospel to new and larger audiences. As they became increasingly Republican, Jerry Falwell and others became more openly political, reinforcing on Sundays the partisan message their viewers were receiving secularly during the rest of the week.

By the new millennium, the forces pushing America toward greater partisanship had become so mutually reinforcing that it was nearly impossible for politics to break out of the cycle. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, momentarily paused the whirlwind, but the Patriot Act of two months later unleashed it again. The respite was even shorter at the beginning of the covid pandemic in 2020; within weeks masks had been transformed from items of public health to emblems of partisan identity.

Astronomers have been observing Jupiter’s Great Red Spot since the 17th century. This makes it much older than America’s perfect political storm. But if we allow for the fact that Jupiter’s years are twelve times as long as Earth’s, the difference in terms of planetary dynamics isn’t great. Some astronomers think Jupiter’s cyclone will one day break up of its own whirling energy. Maybe Earth’s will too.

Another thought-provoking post, Bill. I will most definitely be using this with my Government students next year when we discuss political parties & partisanship. I might even give it to my U.S. History students next year when we start discussing Jefferson & the emergence of political parties in the early 1800s.

An editing note: You said “But by the beginning of the 20th century, the middle had vanished.” Did you mean to say that the middle had vanished by the beginning of the 21st century?

I understand the factors you outline driving partisanship, but you (like much of the press and punditry) give the misleading impression that it’s been basically symmetrical on both sides. Yet, on the Democratic side, the partisans have often lost out, with more centrist contenders like Carter, Clinton and Biden beating more progressive rivals, while the Republicans meanwhile have gone off the absolute, looney-tunes deep end.