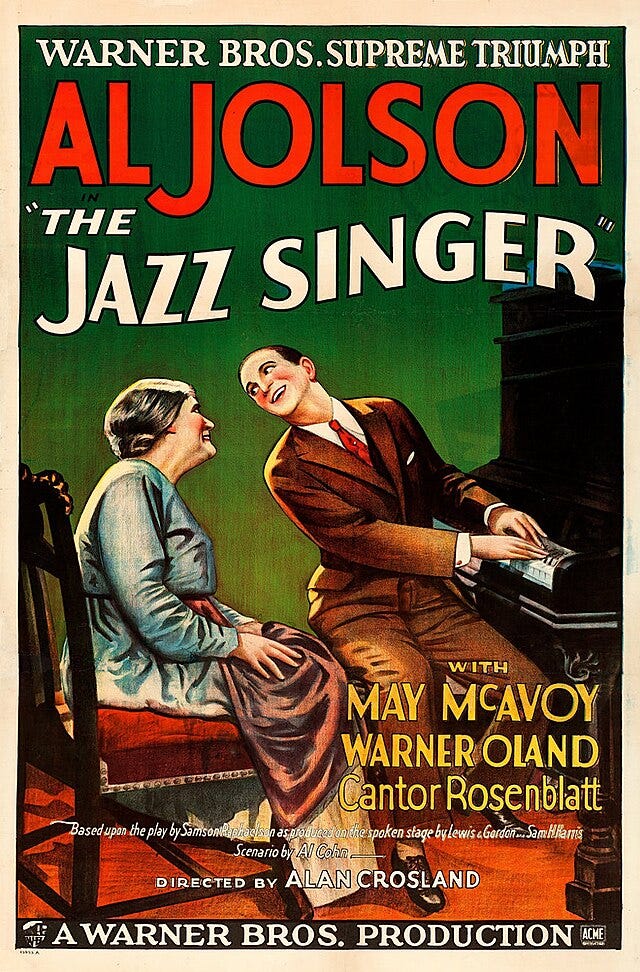

The beginning of the end of the age of literacy commenced in 1927 when Al Jolson spoke words that viewers of the film The Jazz Singer could hear.

Literacy had had a good long run. Or so it seemed at the time. In fact, though, measured against the age of Homo sapiens, it was hardly a flicker. Human language is scores of thousands of years old. Language initially served utilitarian purposes. Look out, there's a tiger! Or, We’ll attack the enemy at dawn. Other apes communicated almost as well.

But human language acquired a distinctive purpose. Humans learned to tell stories. At first the stories were true, about how I tracked and killed that deer, or how my sweetheart did me wrong. In time, humans discovered they could make up stories. Again, some of the stories were utilitarian. I don't know how that thief from our rivals got in and stole our weapons. It's not like I fell asleep or anything.

Other stories were grander. They told of gods and heroes and how our people came to be. Stories inspired us in times of challenge and consoled us in times of grief. Storytellers became honored figures. Priests told stories. Poets told stories. Stories made sense of the world and made nations of separate bands.

The stories were passed from generation to generation by word of mouth, until some people devised methods of recording them in symbols on wood, clay, skins and papyrus. The age of literacy began.

But only for a favored few. The symbols were hard to master and the media expensive to reproduce. Many centuries later, however, a clever German named Gutenberg figured out how to make many reproductions at once. The cost fell dramatically, putting written records before the masses for the first time. Thus began the age of common literacy.

It was no accident that the age of common literacy was the age of revolutions. The first revolution was religious, shaking the Christian church into competing sects. A second revolution was scientific, challenging religious beliefs in the light of human reason. A third revolution was political, inspiring plain people to demand the ability to govern themselves. A fourth revolution was industrial, as new knowledge was applied to processes of production.

Amid the industrial revolution, technologists learned to record reality in photographs and then moving pictures. Yet the photos and the films were silent, and the stories they told didn't capture the popular imagination the way the spoken and written stories had.

Until Al Jolson opened his mouth and words came out. Other films improved on the novelty. Soon talkies were all anyone wanted to see and hear.

Literacy didn't die at once. A hundred years later, literacy is still useful. But decade by decade it becomes less necessary.

The great storytellers of the past were poets like Homer, playwrights like Shakespeare, and novelists like Dickens. The great storytellers of today are film directors like Spielberg and Scorsese.

Literacy has lost much of its utilitarian value. News and other information comes via television and podcasts. Instruction manuals have been displaced by YouTube videos.

Books still exist. But printed books often have audio versions, allowing their consumers to be listeners rather than readers. Intelligent and otherwise well-prepared students can graduate from high school not having been required to read a whole novel or other regular book.

Young people still read and write, but in short bursts of text, email and social media posts. Even these can be produced and consumed by software that converts voice to text and vice versa. Emojis take the place of words. Within social media, text-based forms like Twitter have lost ground to image-based versions like Instagram and TikTok. Signage increasingly relies on internationally accepted symbols.

Literacy has been useful. It made possible the technologies that have superseded it. It will linger, the way Latin lingered in academia and the Catholic church for centuries after it lost broader purpose. Academics and lawyers will be among the last literates.

It’s unclear what their epitaph will be when they finally pass. It’s even less clear that the epitaph will be written. Who will read it?

It is no coincidence that Oxford University Press yesterday announced the “2024 Oxford Word of The Year” is “brain rot.” (Ironically, “brain rot” is technically two words and not one, but I digress.)

The first recorded use of the term apparently was in American writer Henry David Thoreau’s book “Walden” reporting on his experiences of living a simple lifestyle in the natural world, Oxford noted, where he wrote: “While England endeavours to cure the potato rot, will not any endeavour to cure the brain-rot – which prevails so much more widely and fatally?” [I note that Thoreau made it a hyphenated word.]

Oxford explained in its announcement, “Thoreau criticizes society’s tendency to devalue complex ideas, or those that can be interpreted in multiple ways, in favour of simple ones. He sees this as indicative of a general decline in mental and intellectual effort, leading him to ask the question.” Oxford further explained that the phrase was “adopted by Gen Z and Gen Alpha,” gaining new prominence in 2024, “as a term used to capture concerns about the impact of consuming excessive amounts of 'low-quality online content,' especially on social media. A noun, 'brain rot' is defined as the assumed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as the result of overconsumption of material − particularly online content − considered to be trivial or unchallenging. It also is defined as 'something characterized as likely to lead to such deterioration.'”

Oxford Languages President Casper Grathwohl is quoted as saying, “‘Brain rot’ speaks to one of the perceived dangers of virtual life, and how we are using our free time. It feels like a rightful next chapter in the cultural conversation about humanity and technology. It’s not surprising that so many voters embraced the term, endorsing it as our choice this year.“

Shakespeare in Hamlet, knowing of its Biblical use, put the words in Hamlet’s mouth: “Oh, woe is me, T’ have seen what I have seen, see what I see!” (Hamlet Act 3, scene 1)

To bring it forward, “Woe is we.”

Perhaps we should look at it as a "full circle" - the advent of audiobooks etc are bringing us back to the pre-literate era of oral tradition- for good or ill?

I personally prefer a book - a real book- to audio. I can read faster than someone can read TO me. I also prefer a book - a real book - over E-books.