The greatest accomplishment of Thomas Jefferson's presidency, the purchase of Louisiana from France, was indeed a big deal. But it wasn't what it was generally thought to be at the time, and it wasn't what it has typically been understood to be since.

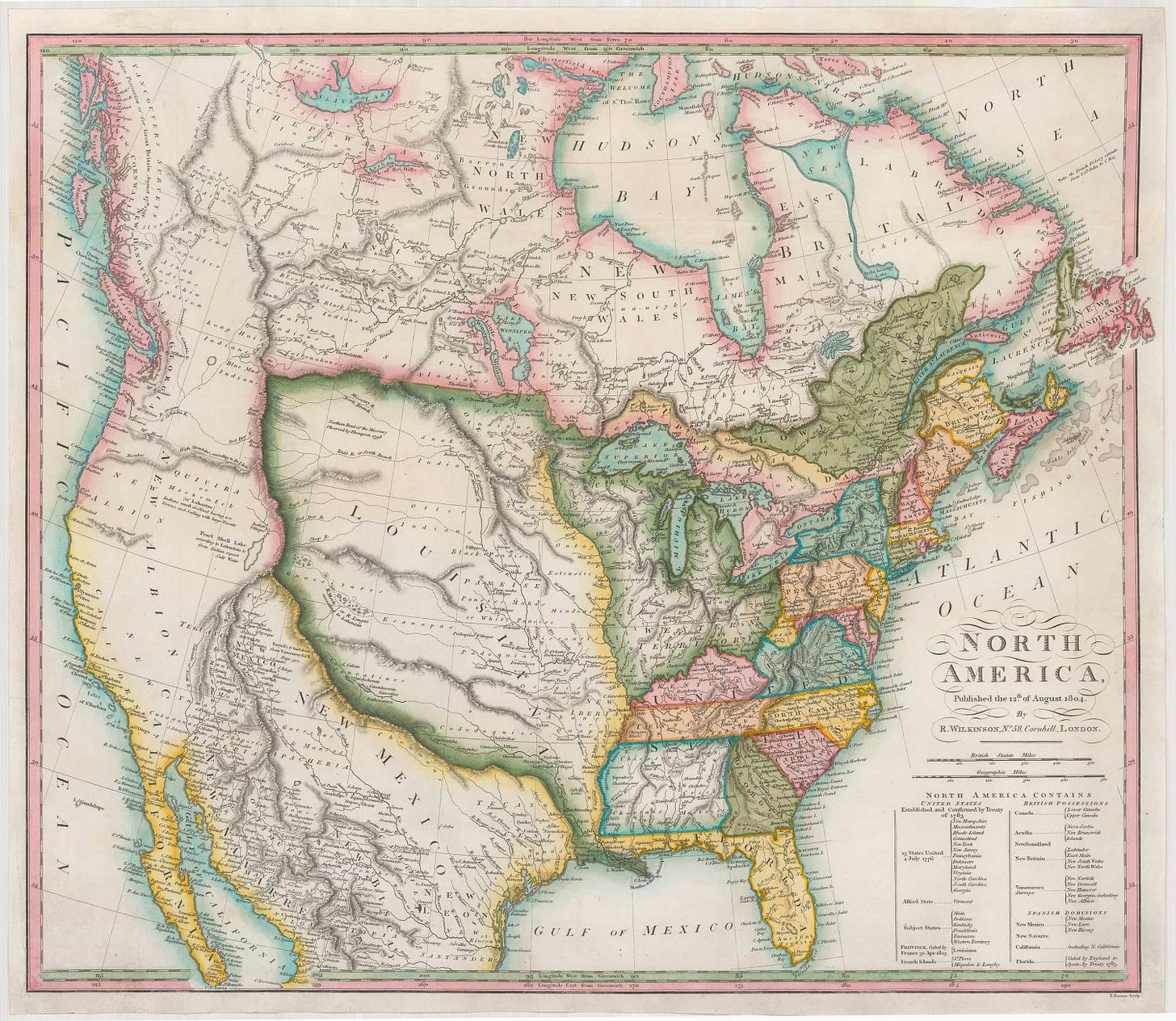

Its importance lay in signaling to the world that the United States would not be content with the territory it acquired at the end of the Revolutionary War. That territory, extending from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River, and from the Great Lakes almost to the Gulf of Mexico, was more than Americans had any right to expect Britain to concede. American arms certainly hadn’t conquered most of that territory. But they had worn out the British, who decided after their defeat at Yorktown that the war had become a losing proposition. The British might well have retained the land between the Appalachians and the Mississippi. In the end, they did so in a de facto manner, continuing to hold forts there in violation of the treaty of Paris. But they nominally ceded it—the eastern half of the Mississipi basin—to the United States, to keep it out of the hands of the French, their abiding enemy.

The Americans would deal with the British later. In the decade after the war, their chief concern regarding the west was the Spanish, who controlled Louisiana, the western half of the Mississippi basin. The Spanish domain included New Orleans, the port city near the mouth of the great river. In those days before railroads, when rivers were the life-sustaining arteries of large countries, the Spanish at New Orleans had a stranglehold on the commerce of the Mississippi and its tributaries, including the Ohio River. Sometimes they squeezed, sometimes they eased. But their presence was always annoying and occasionally intolerable to Americans.

Long before he became president, Jefferson determined that New Orleans must be America's rather than Spain’s. But shortly after he entered the White House he learned that New Orleans wasn't even Spanish anymore. In a bargain intended to be secret, Spain had transferred control of New Orleans and Louisiana to France. Had this happened a decade earlier, Jefferson would have been reassured. He had then considered France a friendly country, the ally who aided the American victory in the Revolutionary War. But Napoleon had since seized power in Paris and subverted the aims of the French revolution. Jefferson was certain Napoleon was no friend of America.

Jefferson sent envoys to Paris to offer to purchase New Orleans. Napoleon surprised them with a counteroffer: all of Louisiana.

Jefferson gulped. The land deal was luscious. Jefferson believed American democracy depended on the prosperity of American farmers. Their numbers were growing rapidly. Consequently the land available to them must grow too. Louisiana would secure the future of American democracy far into the future.

But Jefferson was a stickler on the Constitution. What powers the Constitution did not expressly grant to Congress or the president were powers they did not have, he believed. The Constitution said nothing about acquiring new territory from foreign countries.

Jefferson considered amending the Constitution. But that would take months, perhaps years. Napoleon might change his mind. Jefferson swallowed his scruples and accepted Napoleon's offer.

The Louisiana purchase was immediately celebrated as the real estate deal of the century. Or perhaps the millennium. Jefferson had bought a kingdom for a pittance.

But what, exactly, had he bought? Louisiana was defined as the western half of the watershed of the Mississippi River. Neither Frenchman nor American had been to the headwaters of the Mississippi, and so neither Napoleon nor Jefferson could say how far north Louisiana extended.

The southern reaches of the river were problematic as well. The Spanish controlled Texas, which had never been considered part of Louisiana despite its northeastern portion draining into the Mississippi.

Napoleon scoffed at the uncertainty. He said the Americans had concluded a fine bargain and should make the most of it.

Yet even with this boundary settlement, such as it was, the Louisiana deal was illusive. What Jefferson purchased for America's $15 million was simply Napoleon's abandonment of any French claim to the territory. The Spanish might contest it, as they did contest the claim of Jefferson's successors that Louisiana included Texas. The British might contest it, as they did contest control of the northernmost regions of the Mississippi watershed.

Most importantly, the many thousands of American Indians who lived in Louisiana contested it. They had never accepted the claims of France and Spain to Louisiana, and there was no reason to believe they would accept the claim of the United States.

Simply put, the Louisiana purchase gave Americans the legal right to launch a campaign of dispossession against the indigenous inhabitants of the region. The campaign consumed nearly a century. The last blood was shed on the banks of Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota in 1890.

A very fine overview of this important Jefferson legacy. Indeed how could Jefferson not cede to the purchase? And equally important were the many events within this new territory that added to the American story.