I spent my boyhood summers at a house my grandparents owned on the southwest slope of Mount Hood in Oregon. U.S highway 26 bordered the property. This route had historic significance, for it followed the same path as the western end of the Oregon Trail of the 1840s and 1850s. A few miles up the road, just above the community of Rhododendron, was the Tollgate campground of the Mount Hood National Forest. The part of the Oregon Trail here was called the Barlow Road, for Sam Barlow, the pioneering entrepreneur who built it. The campground occupied a site where a steep hillside pinned the Barlow Road next to the Zigzag River. At this point Barlow had placed a gate across the road. Travelers were required to pay a toll before the gate would open and let them pass.

All this was an early lesson to me that roads had to be paid for. If the public didn't pay for them, users did. Toll roads were common in the early days of settlement of new regions in America, but as population densities increased, the public, acting through government, typically took over. Sam Barlow's road eventually became part of U.S. 26, which runs from Ogallala, Nebraska, to Seaside, Oregon.

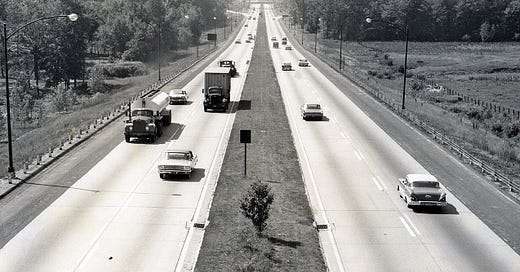

The federal highway system was a patchwork cobbled together over many decades, until it received an enormous boost from the largest public works project in world history until that time. In 1956 Dwight Eisenhower signed the Interstate and Defense Highways Act. This measure called for the construction of a network of limited-access highways across the country.

The “Interstate" part of the title was obvious. The new highways would link the various states together. The "Defense” required more explanation. Part of it reflected Eisenhower's experience in Germany during and after the World War II. He saw the system of autobahns the Germans had built to allow the rapid transfer of military forces from one part of the country to another. The United States had no comparable system, and Eisenhower thought America needed one.

Part of the explanation was a matter of branding. Since the early twentieth century, when America's automobile age began, numerous people had pointed out the inadequacy of the roads America inherited from the age of horse-drawn vehicles. Eisenhower himself had been part of an army convoy that required nine weeks to travel from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco in 1919. Almost four decades later, no broad program had upgraded the old roads. Other items claimed priority in the minds of members of Congress.

The Cold War gave Eisenhower the leverage he needed to change the legislators' thinking. Amid the contest with communism, anything labeled “defense” provided lawmakers political cover to support federal spending. With defense in the title, the roads bill rolled through Congress.

The original interstate highway system took decades to complete. During that time, military convoys were often seen on the new four-lane, divided roads.

But they turned out to be a small part of the traffic. Personal automobiles and commercial trucks formed the vast majority. Both categories eroded the dominance of railroads in American transport over the medium and long distances the interstates spanned.

More dramatic was the effect of the interstate highway system on the growth of American cities and suburbs. A rule of thumb roughly consistent over ages indicated that workers would be willing to live as far as half an hour's journey from their workplaces. Beyond that, especially in eras when a work day might last twelve hours, there simply wasn't time to get to and from work and do the other things necessary to keep body and soul together. Before motorized transport, this meant workers lived within a radius of two miles of their workplaces. Railroads, including subways and tramlines, extended the half hour distance to several miles or more. But the suburbs they created were linear, along the rail lines. The best example was the so-called “Main Line” of suburbs west of Philadelphia along the tracks of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Automobiles and interstate highways reconfigured cities and their suburbs again. In a car on the new thruways a worker might drive twenty-five miles in half an hour. Or he might drive ten miles on the thruway and five miles in any direction from there.

By this means the interstate system made possible the creation of the urban and suburban landscape that characterizes America today. In this landscape the middle class flourished. Families lived in freestanding homes on lots cheap on account of the quantity of land made accessible by the new highways. The homes had yards. The streets were lined with sidewalks the children took to neighborhood schools.

Critics called the suburbs sprawl. The middle class called them home. In time the suburbs became victims of their own success. Growing populations clogged the new roads, extending commute times to an hour or more. Besides depending on the interstates, the suburbs needed cheap gasoline. When oil prices rose in the 1970s, many commuters felt trapped by their suburban lifestyle.

And when in the twenty-first century, climate change became an issue, many Americans felt trapped by the suburban lifestyle the interstates had fostered. More than in other countries, daily life in America depended on access to private automobiles. Population densities in American metropolitan areas were too low to support mass transit. The freedom provided by private cars was part of American culture, but even if it hadn't been, logistics would have prevented their abandonment in favor of buses and the like.

“We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us," said Winston Churchill. He might have said something similar about cities. In America we're still being shaped by the cities our interstate highways created.

As an urban planning geek I really enjoyed this piece. I find the unintended consequences of major public works projects fascinating. The geography of manufacturing today is partly a consequence of the TVA and cheap electricity costs.

Questions: Were there critiques of the interstate highway plan at the time? Are there any good books on this massive public works projects?

My now deceased father. In law for the company clerk in the army between world war two and korea and told us the story of driving from the midwest to the west coast with this company. He and his assistant. We're drive ahead in a Jeep and secure camping rights at local drive in theaters. Although his buddies flipped him the bird as he passed the convoy each day because he and the assistant used to sleep in motels.

Definitely, eisenhower was far thinking with the example in germany, but the downside of the interstates when they became run amuck tearing through urban neighborhoods usually black, black and brown and poor people and splitting cities in half

My own city, which you have been to numerous times Grand Rapids. It's just one such city, where u s one thirty one it cuts right through the heart of the city, separating the west side from the east side like a big moat