One by one the great war chiefs had surrendered. Or died fighting. Tecumseh, Red Cloud, Cochise, Quanah, Satanta, Captain Jack, Crazy Horse, Young Joseph and dozens more. In the mid-1880s Geronimo was the last holdout. Even he had surrendered but then changed his mind and broken out of the reservation that held his band of Apaches.

His followers weren’t thrilled. They saw more clearly than he that the old ways were doomed. Those ways survived longer in Arizona than in other parts of the American West, primarily because Arizona possessed little for white settlers to covet. But finally they came: railroad surveyors, mining prospectors, cattle ranchers. And with them came soldiers.

Geronimo treated them as he had long treated Mexicans—as targets for raids and thus sources of sustenance. Against the Mexicans he had an additional grievance: the slaughter of his family during a time of truce. But Americans who guarded their rail routes or mines or cattle against his raids were just as likely to wind up dead.

The soldiers alone couldn’t catch him. He knew the country too well. He could live off the land where they required supply lines.

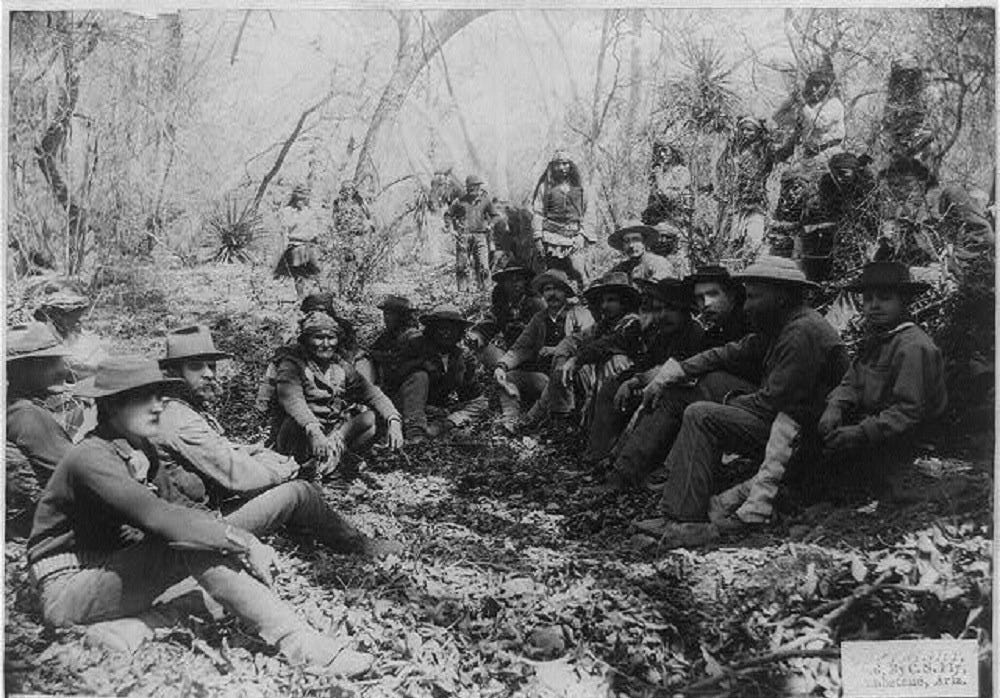

But the soldiers had allies: other Indians, sometimes Geronimo’s enemies, sometimes members of his own tribe. The former were happy to settle scores. The latter thought Geronimo’s stubbornness would bring additional suffering on them all. Both groups found the army’s offer of pay hard to resist.

The Indian army scouts were as indefatigable as Geronimo. They knew the country almost as well as he did. Their travel wasn’t slowed by women and children, as his was.

It was always the women and children that made the difference between the Indians and the army. The Indian warriors would have fought on, likely to their own deaths, but that would have left their dependents defenseless.

Geronimo tried to bargain for himself and for them. He sought assurance that they wouldn't be sent out of Arizona. He later claimed he received such assurance from Nelson Miles, the army commander. Miles denied giving any such guarantee.

After Geronimo surrendered, he and those close to him were sent to far-off Florida, from which yet another breakout was all but inconceivable.

Geronimo’s surrender concluded a long, long chapter in the history of America. For ten thousand years, humans had fought among themselves for control of the territory that would become the United States. Tribe displaced tribe in the endless war. About the time of Geronimo’s birth, a new tribe of people with pale skins arrived in Arizona. These latecomers to the war proved fierce and numerous. And they were united in a way the Indian tribes never were. Indian tribe after Indian tribe gave way before them, until only Geronimo was left. And when he surrendered in 1886, the war for America ended, in victory for the pale-skinned tribe.

Geronimo was allowed to return to the west but not to Arizona. At Fort Sill in Oklahoma, he told his life story to an interested writer, who published it. Geronimo converted to Christianity, accepting baptism in the Dutch Reformed Church.

Why this sect? Perhaps because the president of the United States at the time, Theodore Roosevelt, was Dutch Reformed. Geronimo asked Roosevelt to let him return to Arizona. Roosevelt admired Geronimo as a brave warrior and an unsurpassed military tactician. But he refused permission, knowing that many Arizonans still deemed Geronimo a murderer and sought revenge.

Geronimo died at Fort Sill in 1909, a few months before his eightieth birthday.