In the 18th century Benjamin Franklin quantified a defining characteristic of American life. There was no regular census then, but Franklin cobbled together various statistics to conclude that the population of the British colonies in North America was doubling roughly every generation. Franklin would not have called himself a mathematician, but he understood the implications of exponential growth. He noted that before long the population of British North America would outstrip the population of Britain. He urged Parliament to prepare for this day and allow America to become an equal partner in a transatlantic British empire. It would be the greatest thing ever, Franklin said, a blessing to Britain and America both, and a beacon for humanity in general.

To the extent the British believed him, they took alarm rather than encouragement from Franklin's projections. Rather than accommodate the Americans, they constricted the Americans and in the process doomed the empire to the loss of the American colonies south of Canada.

Population growth hardly registered the change of government in America. Americans procreated as lustily as ever, and the independent republic was even more attractive to immigrants from abroad. Population growth drove American territorial expansion. When most people made their living from the land, a growing population required a growing territory.

Even after industrialization reduced the comparative importance of agriculture, the insatiable demand for workers in mines and mills meant ample jobs for native born Americans and for immigrants too.

Expectations of continued population growth were built into the American economy and into American politics. The single most common method by which Americans increased their wealth over time was the purchase and subsequent sale of real estate. Growing populations drove up property values, enriching one generation after another. And when in the 20th century the American government began weaving a social safety net, it was premised on the assumption that the number of people paying for the safety net—that is, taxpayers—would grow every generation.

America's population growth had never been strictly uniform. Wars discouraged immigration, and depressions dampened procreation. But the wars and the depressions ended, and growth resumed.

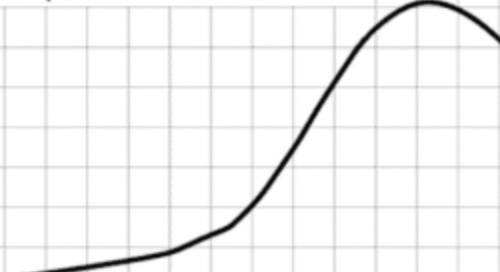

Until around the 2010s. The large families of the post-world War II Baby Boom gave way to much smaller families. In the 1950s, the American birth rate was about 25 births per 1,000 people per year. In the 2010s it was 13 per 1,000. The average American woman had around three children in her lifetime in the 1950s. In the 2010s, the average was 1.6.

This last figure was striking. For a society to maintain a stable population, exclusive of immigration, the average number of births per woman must be about 2.1. In the event, in America immigration more than made up the difference. Into the 2020s, the American population was still growing. But it was growing more slowly than before, and indeed the population was projected to begin falling during the second half of the 21st century.

The prospect of falling population was hardly peculiar to America. In many other countries, population decline had already set in. China's population was projected to decline by nearly half by the end of the century. By then the overall population of the world would likely be falling.

This would be momentous. Never in recorded history had the human population declined. Epidemics could cause particular populations to plummet. The Black Death of the 14th century killed a third of the European population. The indigenous populations of the Americas were even harder hit following contact with European explorers and colonists. But for ten thousand years the graph of overall human population had had a positive slope. Now it appeared about to peak and tip down.

If it did, humanity would be in uncharted territory. America had experienced regional declines. The population of the northern Great Plains peaked around 1900 and fell steadily after that. Cities like Buffalo, Cleveland and Detroit became shadows of their industrial selves. But those population declines were a matter of redistribution: people moving elsewhere. For the nation's population as a whole to decline was something different.

It would compel a new arithmetic of government, as fewer young people were available to support their elders. It almost certainly would temper opposition to immigration.

More profoundly, it would alter Americans’ perceptions of themselves. America had always been the land of the future, partly because in the future there would always be more Americans. How could Americans get excited about a future in which they dwindled away?

None of this was etched in stone. The cause of the decline in population was the cumulative decision of each generation to have fewer children than their parents had had. Perhaps future generations would make different decisions.

Governments were already trying to get them to do so, offering cash payments for children, support for child care, and other family-friendly enticements. None seem to be working. The decision to have fewer children or none at all wasn't being made lightly. And it wouldn't be unmade lightly.

Some people liked the idea of fewer humans. Cities and countries would be less crowded. The human impact on the global environment would be reduced. Competition for resources would diminish.

Where would it end? No one knew.

(This is the final installment of the “25 for 25” series describing a key event or development from each of America’s first 25 decades.)

The ability of women to control when and if they gave birth has been one of the major factors in declining population numbers. Before the 20th century, they had no choice at all about their reproduction; now it hangs on whether they want to do it or not.

In the May 2017 Social Security Bulletin, it was reported that “… about half of the population aged 65 or older live in households that receive at least 50 percent of their family income from Social Security benefits and about 25 percent of aged households rely on Social Security benefits for at least 90 percent of their family income.” In June 2024, the United States Census Bureau reported that “[m]any older adults rely heavily on Social Security, the largest anti-poverty program in the United States, and research shows it was the sole source of income for 28% of adult recipients in 2021.” According to the Social Security Administration's 2023 Trustees Report, the Social Security trust fund is projected to become insolvent in 2034.

If we do not have sufficient wage earners in the future paying into the system, where will we be? Where will you be? Where will I’ll be? I wonder.

Said another way, Si no tenemos suficientes asalariados en el futuro pagando en el sistema, ¿dónde estaremos? ¿Dónde estarás? ¿Dónde estaré? Me pregunto.