George Washington disliked slavery. “I am principled against this kind of traffic in the human species,” he wrote. Thomas Jefferson liked it even less. “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just, that his justice cannot sleep forever,” Jefferson wrote in reference to the evil America was storing up for itself by practicing slavery.

Yet Washington and Jefferson hoped America's problem would solve itself. In Virginia, the oldest colony and the most populous state, and the one with the most slaves, tobacco had worn out the soil. The crop that saved Jamestown and drawn investment to the Chesapeake region had run its course. Washington got out of tobacco and into grains and a variety of other crops less labor intensive than tobacco. He supposed his neighbors would too. As they did, they’d discover the efficiencies of paid labor, which could be matched to seasonal need and which didn't tie up capital the way enslaved labor did. The vile institution would die of unprofitability.

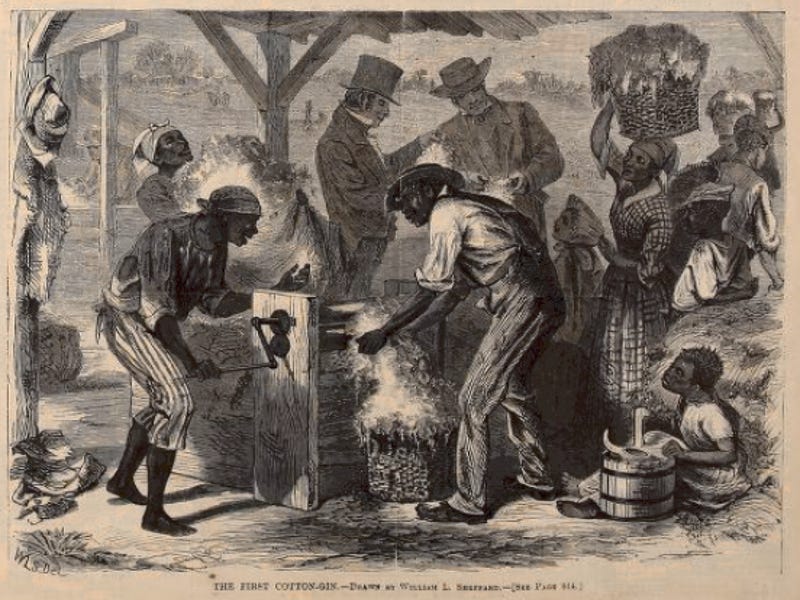

Eli Whitney wasn't thinking about the structure of the southern work force. He wasn't especially concerned about slavery, being from New England, where slaves were few. His inventive mind was engaged with a technical problem. After starting a job in Georgia as a tutor, he learned that cotton growers couldn't figure out a good way to separate cotton fibers from cotton seeds in the variety that grew best in most of the south. Whitney set himself the challenge of solving the problem.

He crafted a hand-operated engine—or “gin"—with metal teeth that dragged cotton bolls through a wire mesh too fine to pass the seeds. Upon improvement it greatly increased the productivity of the workers cleaning the cotton. This allowed the price of finished cotton to decline dramatically. Heretofore cotton cloth and clothing had been luxury items more expensive than wool. Now they became affordable for the many.

Whitney made little money from his cotton gin. His business acumen didn't match his inventiveness.

But southern cotton planters made lots of money. A cotton boom developed as cultivation of the suddenly profitable crop spread west across the Gulf Coast plain all the way to Texas. Each new plantation required a new workforce of slaves. At the constitutional convention of 1787 southern planters had acquiesced in the termination of slave imports to the United States, effective in twenty years. This meant that the new demand for slaves had to be met domestically. The price of slaves rose sharply, and an internal traffic developed from Virginia and other eastern states to the west. Plantations exhausted by tobacco became profitable again, as suppliers of slaves. The hopes of the likes of Washington and Jefferson that slavery would sink under its own weight were what sank, beneath the surging profits from western cotton.

Human history is full of unintended consequences. Eli Whitney sought to solve a technical problem and did so, only to create a political problem that wasn't resolved before America had fought a bloody civil war.

Ironically, or not, Whitney contributed to that as well. He pioneered the principle of interchangeable parts in the manufacture of American firearms, accelerating production and ensuring that when the armies of the Union and the Confederacy clashed, each killed many thousands of the other.

Perhaps he should have stuck to tutoring.

"George Washington disliked slavery. “I am principled against this kind of traffic in the human species,” he wrote. Thomas Jefferson liked it even less. “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just, that his justice cannot sleep forever,” Jefferson wrote in reference to the evil America was storing up for itself by practicing slavery."

Everyone as of late who has been calling Washington and Jefferson evil slave-masters without consciences should read that.

Washington and Jefferson, like most other slave-owners, were trapped by an economic system. Most slaves, like homes today, were mortgaged. Free your slaves, you still owe the debt, and your farm goes to seed.